By Akasha L. Khalsa

The Language

The native language of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (U.P.), and of the wider Great Lakes region, happens to be one of the world’s most complex and difficult to learn (Pitawanakwat, 2009). It is also endangered, with few living speakers remaining. For most English speakers in the area, the only exposure they may have to its existence is in certain place names they encounter. For example, the name of the city of Munising comes from minisiin (island), and Mackinac Island or Michilimackinac comes from michaa (it is big) and mikinaak (turtle).

This language is Anishinaabemowin. It is spoken by the Anishinaabe, the indigenous peoples of the Three Fires Confederacy, consisting of the Odawa (or Ottawa), the Ojibwe (sometimes Ojibway or Chippewa), and the Potawatomi (or Bodéwadmi). The language Anishinaabemowin is also referred to as Ojibwe, Odawa, Saulteaux, Nishnaabemwin, Bodéwadmimwen, and other similar terms. It is spoken in Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin, North Dakota (due to relocation of Anishinaabe communities), Oklahoma (also due to relocation), Manitoba, Ontario, Saskatchewan, and Quebec (Nichols, 1992).

Despite centuries of aggressive government policies aiming to eradicate the language in the United States and Canada, it remains in pockets. It is still spoken by some in the U.P., and many revitalization efforts in the area seek to preserve its use. Anishinaabemowin is one of few endangered native languages in the Americas which are expected to survive past the year 2100; yet its use in the future beyond is not guaranteed (Pitawanakwat, 2009). Numbers of fluent speakers continue to fall, as many are elders and more pass away each year. For those who speak this language or consider it part of their heritage, its moribund status is a dire threat. The immense spiritual and cultural value of Anishinaabemowin makes it crucially important for Anishinaabe communities, and the history of oppressive government policies such as boarding schools also lends it vital importance (Morgan, 2005). Efforts to rehabilitate the language in recent decades have resulted in a new generation of young speakers coming into their own. Anishinaabemowin language instructors are in high demand to fill positions in immersion classrooms, cultural offices within tribes, and even university instruction. Additionally, literature in and about the language has created a national conversation about its survival. The positive impact of revitalization efforts can be felt even by adult language learners in the U.P.

Some research exists on Anishinaabemowin revitalization efforts in Canada, in Minnesota, and in Michigan’s lower peninsula. However, not much can be found on specific resources and revitalization initiatives in the Upper Peninsula. In fact, the isolated region is often glossed over. Yet language learners in the U.P. face particular challenges in finding resources for Anishinaabemowin, and research on their experiences is therefore necessary to inform how revitalization programs can aid them.

Missionaries

Catholic missionaries made a significant impact on the documentation (and therefore survival) of this language, although their intention was to replace rather than preserve indigenous culture. The most significant contribution of note in the U.P. is Bishop Frederic Baraga’s Dictionary of the Otchipwe Language, first published in 1853. His Dictionary retains its usefulness for linguists, revitalization programs, and even sometimes Anishinaabemowin learners. In a 1992 edition of the dictionary, editor Nichols noted that:

Language teachers across the Upper Midwest and Eastern and Central Canada, whether they speak Algonquin, Chippewa, Ojibway, Ottawa, or Saulteaux, continue to find the dictionary a useful reference, one which reminds them and community elders of old words, rarely heard today or totally lost. (p. v)

For scholars focusing specifically on Michigan’s U.P., the dictionary is of particular importance as it provides a representation of the dialect particular to the region during the 1800s when Baraga was learning and recording the language. Nichols notes, “The main dialects represented in the [Baraga] dictionary are those that were spoken 150 years ago on the south shore of Lake Superior” (Nichols, 1992, p. vii). Baraga expressed his intention for the dictionary to be used solely by European academics studying a dead language, as he believed that Native American peoples would be eradicated (Nichols, 1992). Yet Anishinaabemowin survived, and so did the people who speak it. In some cases, we see that the actions of missionaries who sought to eliminate Anishinaabe culture and language even contributed to the preservation of indigenous language, culture, and spiritual identity.

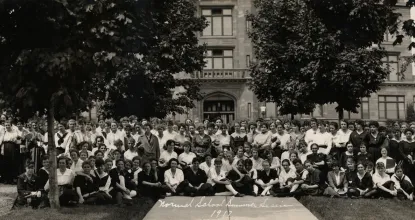

That was the case with Anishinaabemowin translations of hymns and the Bible. At first, these translations were carried out by the missionaries themselves. However, some Bibles and hymnals were translated by Anishinaabe people as early as 1829 when Kahkewaquonaby, also known as Peter Jones, published a translation of the Bible in Toronto (Korpan, 2021). Ojibwe hymns are still often sung in certain ceremonial contexts in Anishinaabe communities around the Great Lakes. Fairbanks noted in 2015 that communities continue to sing the songs in the Ojibwa Hymnal 1910, translated by Kah-O-Sed, even when singers no longer know the meaning of the Anishinaabemowin words: “they value the language to the point of singing songs by rote to keep the sound of the language alive” (p. x). Fairbanks also found that some singers try to use the songs to learn the language (2015).

Upper Peninsula Tribes

Many of the five federally recognized Anishinaabe tribes in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula have programs aimed at preserving their ancestral language. These programs are often labeled culture divisions. For example, the Bay Mills Cultural Program, staffed by only three individuals, is tasked with ensuring that Anishinaabe culture, including language, is passed on to future generations (Bay Mills Tribal Administration, n.d.). In addition, the Bay Mills Community College offers an Associate of Arts in Anishinaabe Language Instruction. Bay Mills also created the Anishnaabemwin Pane Immersion Program, which is a 4- or 6-year diploma (Bay Mills Community College, 2021).

The Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians currently offers online language classes which are free and open to the public (Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, 2021). The Sault Tribe Language and Culture Division consists of five departments, one of which focuses exclusively on Anishinaabemowin. This department states that they offer community classes for participants across seven counties, as well as providing livestream and Facebook lessons, assistance with translations and projects, and a monthly language lesson printed in the tribe’s Win Awenen Nisitotung Newspaper (Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, 2021). On top of these activities, the department holds an annual language conference.

The Hannahville Potawatomi Indian Community handles language preservation through their Culture Committee. They work to offer cultural activities such as Potawatomi Language programs, ceremonies, an annual Pow Wow, and the Annual Potawatomi Gathering of the Nations (Hannahville Indian Community, 2013). The tribe’s Potawatomi Heritage Center also has language programs, and their Nah Tah Wahsh Psa Hannahville Indian School includes a department of Potawatomi Language & Culture (Nah Tah Wahsh PSA & Hannahville Indian School, 2021).

The Keweenaw Bay Indian Community’s Ojibwa Community College offers two courses in “Ojibwa Language and Culture” (Keweenaw Bay Ojibwa Community College Board of Regents, 2020). Meanwhile, the Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians’ Tribal Historic Preservation Office states, “The Tribal Historic Preservation Office will work in collaboration within the Getegitigaaning Ojibwe Nation Language program to do what ever is necessary for the maintenance of our Ojibwe Language” (Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, 2021). According to Lac Vieux’s Wiindamaagewin (newsletter), the tribe sometimes hosts a “Language and Cultural Camp” in cooperation with the Getegitiagaaning Tribal Historic Preservation Office.

Colleges and Universities

The Upper Peninsula is home to several colleges and universities, some of which offer or have offered Anishinaabemowin classes. Northern Michigan University holds language classes as part of their Center for Native American Studies, which offers a bachelors in Native American Studies (NMU Board of Trustees, 2021). As of 2020, Lake Superior State University, located in Sault Ste. Marie, offered a minor in “Anishinaabemowin/Ojibway Language and Literature” (Lake Superior State University, 2016). However, the college no longer offers this minor.

As mentioned above, the Bay Mills Tribal College offers the Anishnaabemwin Pane immersion program. This program is significant in that it “has developed a much needed and recognized process of Anishinaabemwin language learning utilizing the concept that is found in the Medicine Wheel Teachings” (Bay Mills Community College, 2020a). Immersion instruction is highly sought after by students wishing to learn the language, especially those who want to learn in a way that is in line with the history of oral learning of the language. The college also offers a teacher training program, preparing students to become Anishinaabemowin instructors after two years of studying the language (Bay Mills Community College, 2020b).

State Teaching Standards and Guides

As more young people have gained competency in the language and become instructors in turn, the State of Michigan recognized a need for the creation of standards for teaching it. The Michigan Department of Education adopted “Standards for the Preparation of Teachers of Anishinaabemowin Language & Culture (FN)” in 2011 (Michigan Department of Education, 2011). The standards are intended to prepare K-12 educators and align with established curriculum standards for K-12 courses. Creating state teaching standards for the language is beneficial for its potential to survive as a modern language into the coming century. It serves the purpose of raising the language’s perceived status as a living modern language.

More recently, the Confederation of Michigan Tribal Education Department released the Maawndoonganan: Anishinaabe Resource Manual to Accompany the State of Michigan Social Studies Standards (2021). This resource directs Michigan social studies teachers to resources for accurately representing indigenous peoples. Some of these resources introduce students to Anishinaabemowin, including the audio resource “Sounds of the Birchbark House: Learn and Hear the Anishinaabemowin within the book” and the article “This Six-Year-Old Could Be Part Of A Revival Of The Ojibwe Language” by Ben Meyer (Confederation of Michigan Tribal Education Department, 2021). The resource guide aims to expose more children to the reality of indigeneity in Michigan, and in accomplishing this the guide also exposes these students to the existence of Anishinaabemowin and even the complex issues surrounding its revitalization.

Anishinaabemowin in U.P. Literature

Recognition of the language’s struggle to survive is crucial for its revitalization. Part of this can be accomplished through representation in literature. Michigan’s Upper Peninsula has contributed significant works of Anishinaabe literature which foreground Anishinaabemowin. In fact, the U.P. was home to the first published female indigenous American author, Jane Johnston Schoolcraft, or Bamewawagezhikaquay. Schoolcraft wrote poetry in both English and Anishinaabemowin (Gessner, n.d.). A collection of her writings entitled The Sound the Stars Make Rushing Through the Sky was published in 2008, and it contains text in both tongues.

More recently, Angeline Boulley’s 2021 novel Firekeeper’s Daughter reached a national audience, as it quickly became a #1 New York Times bestseller and is slated for a Netflix adaptation (Boulley, 2021b). Boulley is an enrolled member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, and she based her novel in her tribe. Significantly, this book includes significant discussion of Anishinaabemowin as an endangered language. Boulley addresses the history of boarding schools which aimed to take the language from the Anishinaabe: “[children] had the Anishinaabemowin and cultural teachings beaten out of them” (Boulley, 2021a, p. 100). Firekeeper’s Daughter also includes enough Anishinaabemowin words and grammar concepts to perhaps become the basis of an introductory lesson in the language. Boulley’s novel even ends with a heartfelt prayer that the creator “[keep] our children dreaming in the language” (2021a, p. 488).

Conclusion

The growing awareness of Anishinaabemowin in the Upper Peninsula, and around the Great Lakes Region more broadly, is due to decades of revitalization efforts across state and national boundaries. These efforts have also resulted in the training of young Anishinaabemowin language speakers and instructors. Although elders who speak the language pass away each year, perhaps enough young people will be taught the language to carry it into the future. At Northern Michigan University, Native American Student Association president Bazile Panek reflected:

Now there’s more language speakers, which is awesome, but five, ten years ago I wouldn’t be able to name speakers off the top of my head. I would have to ask around to find out who speaks and what resources I can use. (Personal interview, November 29, 2021)

Along with young speakers, resources such as state-funded teaching standards, children’s books, and literature in and about the language are becoming more common. In short, there is certainly hope for the survival of this ancient language in the Great Lakes region, and in indigenous communities which strive to preserve it in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula specifically.

Akasha L. Khalsa

Northern Michigan University

Akasha Khalsa is a 2022 NMU graduate. She earned a degree in English and French and plans to pursue a graduate degree in language revitalization and documentation. She has published academic work in Conspectus Borealis and worked as a journalist on NMU's campus for four years.

References

Bay Mills Community College. (2020). Anishinaabemwin Language Studies. https://www.bmcc.edu/sites/default/files/diploma_pane_bmcc_catalog_2020-2021.pdf

Bay Mills Community College. (2020). Associate of Arts Anishinaabe Language Instruction. https://www.bmcc.edu/sites/default/files/aa_anishinaabelanguageinstruction_bmcc_catalog_2020-2021.pdf

Bay Mills Community College. (2021). Anishinaabemwin Pane Immersion Program. https://www.bmcc.edu/anishnaabemwin-pane-immersion-program

Bay Mills Tribal Administration. (n.d.). Bay Mills Cultural Program. Bay Mills Indian Community. https://www.baymills.org/about-3

Boulley, A. (2021). Firekeeper’s Daughter. Henry Holt and Company.

Boulley, A. (2021). Angeline Boulley. https://angelineboulley.com/

Confederation of Michigan Tribal Education Department. (2021). Maawndoonganan: Anishinaabe Resource Manual to Accompany the State of Michigan Social Studies Standards.https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdcr/Anishinaabe_Resource_Manual_736915_7.pdf

Fairbanks, J. (2015). Babaamiinwajimojig (People Who Go Around Telling the Good News): Tracing the Text of Ojibwa Hymn No. 35 from 1910 to 2010 (Publication No. 3702524) [Doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Gessner, D. (ed.). (n.d.). Jane Johnston Schoolcraft (Bamewawagezhikaquay). Ecotone. https://ecotonemagazine.org/ecotone-authors/jane-johnston-schoolcraft/

Hannahville Indian Community. (2013). Culture Committee. Keepers of the fire Hannahville Indian Community. http://www.hannahville.net/services/culture-committee/

Keweenaw Bay Ojibwa Community College Board of Regents. (2020, September 14). Catalog 2020-2022. https://www.kbocc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/2020-2022-KBOCC-Catalog.pdf

Korpan, R. L. (2021). Scriptural Relations: Colonial Formations of Anishinaabemowin Bibles in Nineteenth-Century Canada. Material Religion, 17(2), 147-176. 10.1080/17432200.2021.1897279

Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians. (2021). What Does our Tribal Historic Preservation Office do?. Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians. https://lvd-nsn.gov/Content/What-Does-THPO-do.cfm

Lake Superior State University. (2016). Five-Year Facilities Master Plan 2016-2020. Lake Superior State University. https://www.lssu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/2016-20CapitalOutlayMasterPlan_S.pdf

Michigan Department of Education. (2011). Standards for the Preparation of Teachers of Anishinaabemowin Language & Culture (FN). Michigan State Board of Education. https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mde/Anishinaabemowin_Standards_553938_7.pdf

Morgan, M. J. (2005). Redefining the Ojibwe Classroom: Indigenous Language Programs within Large Research Universities. Anthropology and Education Quarterly 36(1), 96-103.

Nah Tah Wahsh PSA & Hannahville Indian School. (2021). Potawatomi Language & Culture. Nah Tah Wahsh PSA & Hannahville Indian School. http://www.hannahvilleschool.net/departments/potawatomi_language___culture

Nichols, John D., Ed. (1992). A Dictionary of the Ojibwe Language. (Baraga, Frederic, Auth.). Minnesota Society Historical Press.

NMU Board of Trustees. (2021). Center for Native American Studies. Northern Michigan University. https://www.nmu.edu/nativeamericanstudies/

Panek, Bazile. (November 29, 2021). Personal interview (Akasha Khalsa, ed.).

Pitawanakwat, Brock. (2009). Anishinaabemodaa Pane Oodenang—A Qualitative Study of Anishinaabe Language Revitalization as Self-Determination in Manitoba and Ontario [Doctoral dissertation, University of Victoria]. UVicSpace. http://hdl.handle.net/1828/1707

Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians. (2021, March 30). Anishinaabemowin (the sound of the Ojibwe Language). Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians. https://saulttribe.com/membership-services/culture/language-department