By Zoe Folsom and Chloe Vander Laan

Northern Normal

At the turn of the 20th century, Michigan’s Upper Peninsula flourished with the immigrants who had come to work in the extractive industries (like logging and copper mining) of the time; from 1900 to 1910 alone, Marquette County’s population grew by 13.3% (U.S. Census Bureau). Despite dangerous working conditions and brutal winters, people decided to make homes for themselves in the vast wilderness of the U.P., and when they had children, those children needed an education. At the time, 75% of the schoolteachers in the area had no formal certification or training and were likely fresh out of secondary school themselves. Wanting better for their communities, notable Marquette residents like Peter White lobbied the state legislature for the establishment of what was then called a Normal School in Marquette. Normal schools had sprung up all over the country in the late 19th century to educate and certify teachers for the growing public schools—they were post-secondary education but granted only teaching credentials. Though the state legislature refused Marquette’s first few proposals, eventually they were convinced. Thus, on April 28, 1899, the institution that would become Northern Michigan University was born.

At the turn of the 20th century, Michigan’s Upper Peninsula flourished with the immigrants who had come to work in the extractive industries (like logging and copper mining) of the time; from 1900 to 1910 alone, Marquette County’s population grew by 13.3% (U.S. Census Bureau). Despite dangerous working conditions and brutal winters, people decided to make homes for themselves in the vast wilderness of the U.P., and when they had children, those children needed an education. At the time, 75% of the schoolteachers in the area had no formal certification or training and were likely fresh out of secondary school themselves. Wanting better for their communities, notable Marquette residents like Peter White lobbied the state legislature for the establishment of what was then called a Normal School in Marquette. Normal schools had sprung up all over the country in the late 19th century to educate and certify teachers for the growing public schools—they were post-secondary education but granted only teaching credentials. Though the state legislature refused Marquette’s first few proposals, eventually they were convinced. Thus, on April 28, 1899, the institution that would become Northern Michigan University was born.

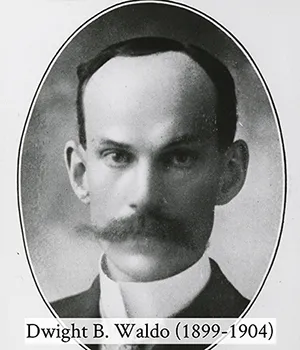

Dwight B. Waldo (1899-1904)

1st President of Northern Normal

An Institution Embedded in its Community

Receiving more support from local benefactors than the state in its early years meant Northern was always an institution embedded in its community. In fact, before the construction of the first educational facility for campus, Northern students took classes in an unused part of Marquette’s City Hall. Constant advocacy for Northern’s importance obtained support from the state, and Northern soon began to realize its dreams of becoming much more than just a place for a few U.P. teachers to receive their teaching certificates.

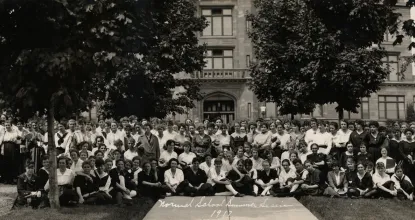

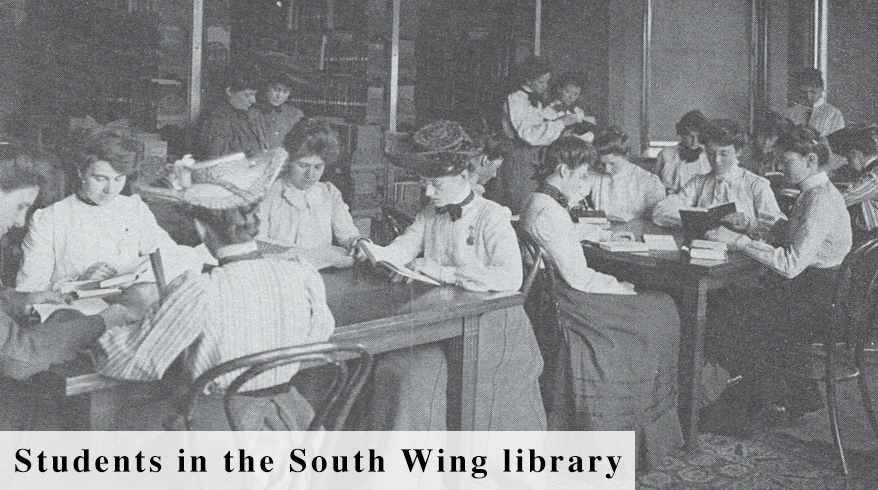

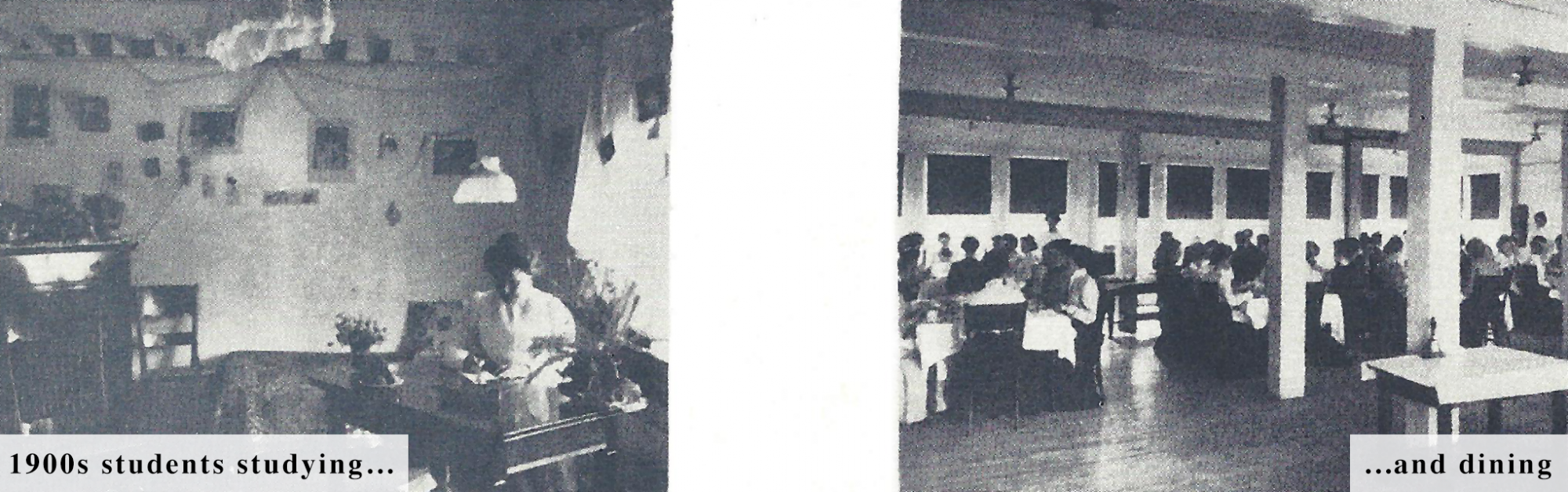

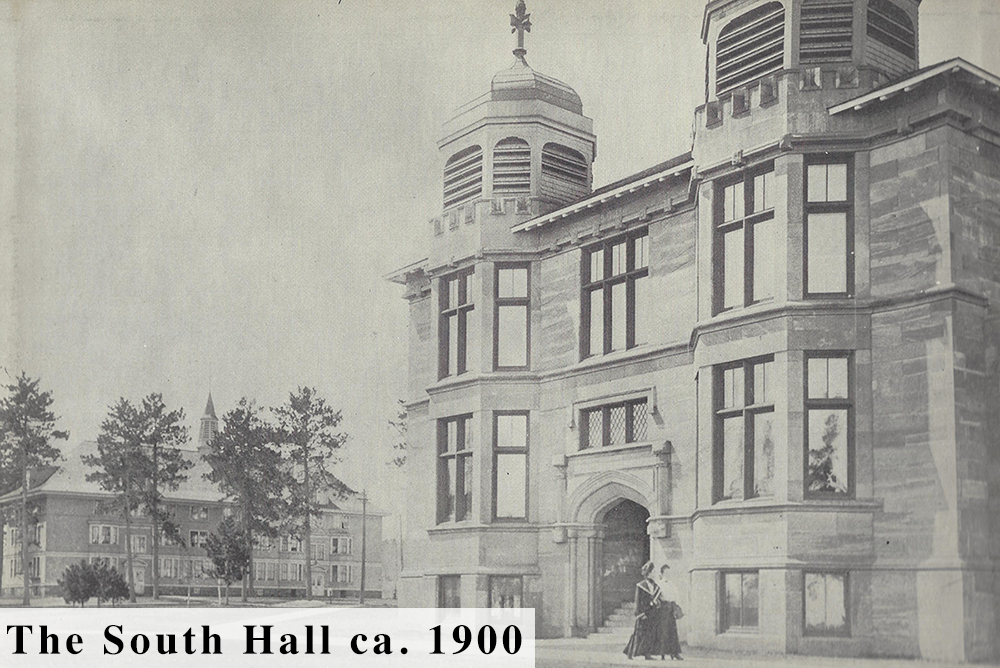

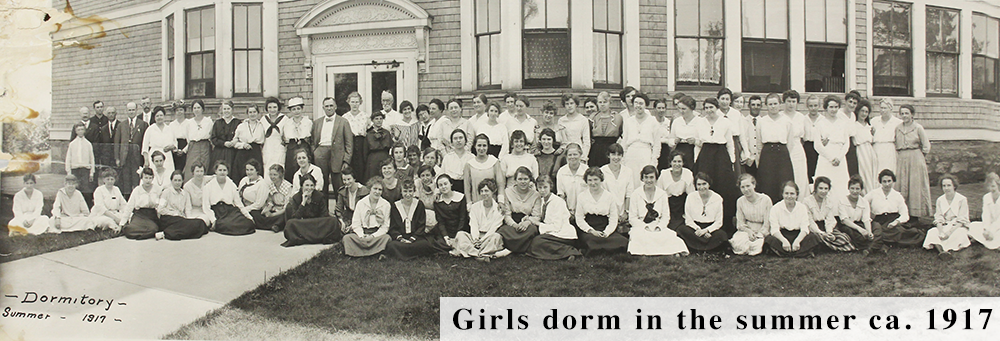

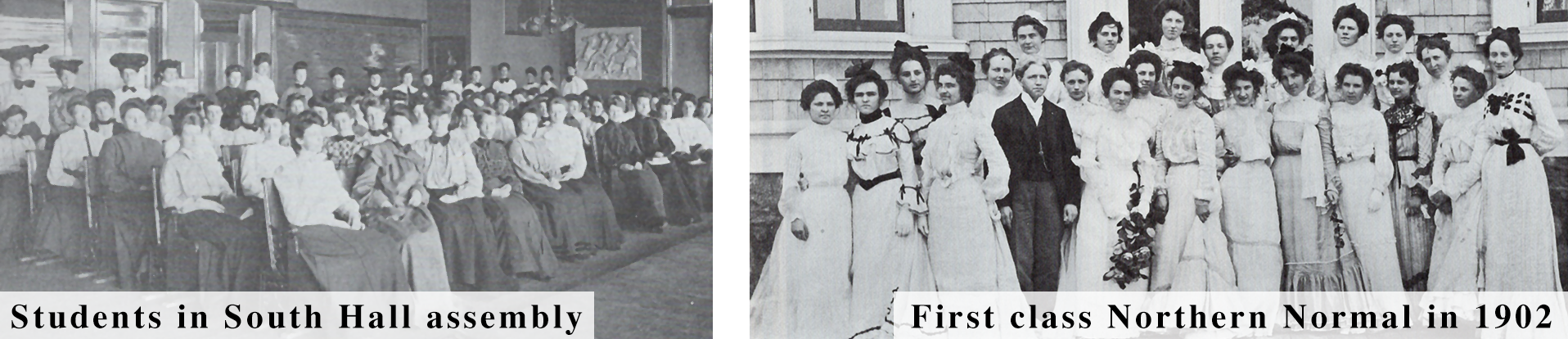

At its outset, Northern Michigan Normal School only offered temporary or lifetime teacher certifications to its graduating students. The students, mostly women who already taught in the rural, largely one-room schoolhouses of the region, came mostly in the summertime (though there were fall and winter semesters as well) to receive instruction at South Hall (later renamed Longyear), and to teach in the John D. Pierce Training school, which educated Marquette’s youth for decades and served as the student-teaching site for all of the students. A vast majority of Northern Normal’s early students had grown up in the U.P. and went on to teach in U.P. schools. They received instruction in subjects like

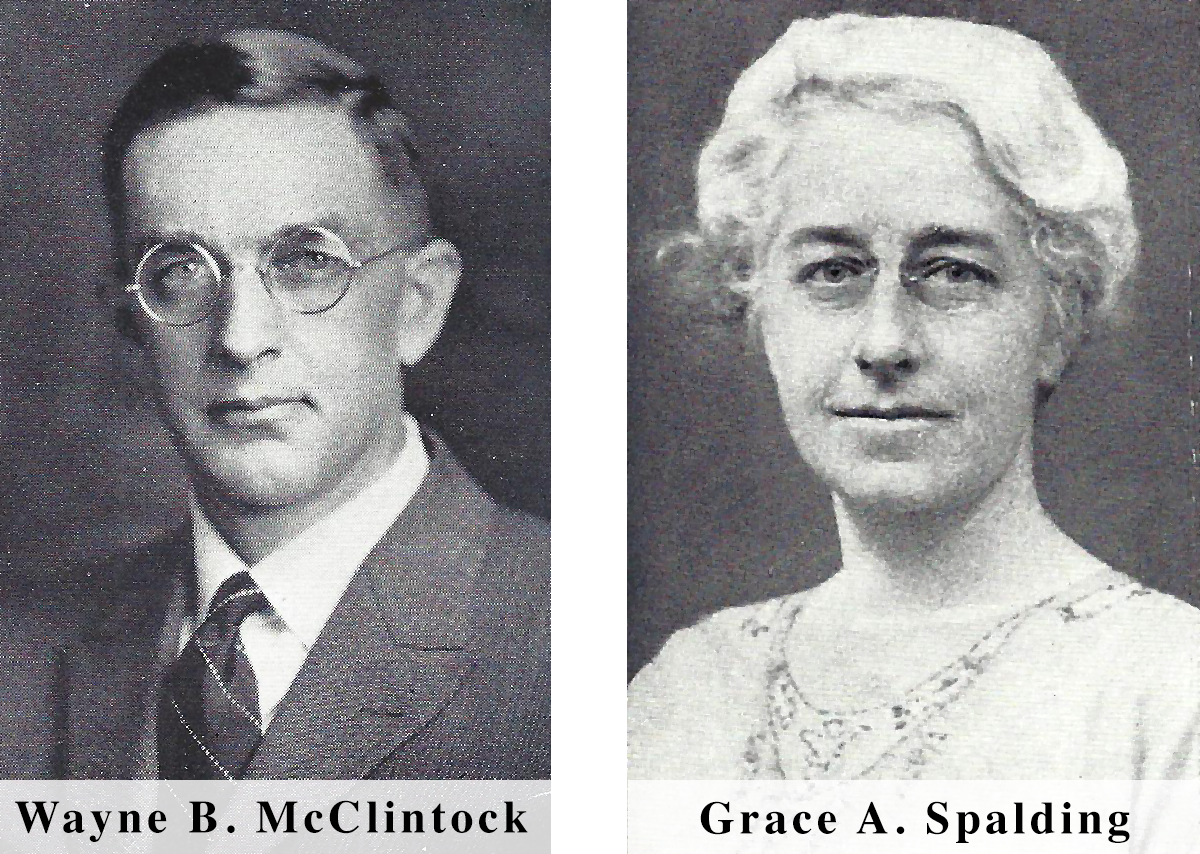

At its outset, Northern Michigan Normal School only offered temporary or lifetime teacher certifications to its graduating students. The students, mostly women who already taught in the rural, largely one-room schoolhouses of the region, came mostly in the summertime (though there were fall and winter semesters as well) to receive instruction at South Hall (later renamed Longyear), and to teach in the John D. Pierce Training school, which educated Marquette’s youth for decades and served as the student-teaching site for all of the students. A vast majority of Northern Normal’s early students had grown up in the U.P. and went on to teach in U.P. schools. They received instruction in subjects like mathematics, English, drawing, and physical education, garnering knowledge and skills they could use in their own classrooms. Instructors such as Grace Spalding, Northern’s art teacher, and Wayne B. McClintock, who taught physical education and organized sporting events outside of class, earned such respect from students and fellow faculty and administration that they’re honored on campus even today in the names of the buildings that educate, house, and support current Northern students. Many of these early professors grew so fond of Northern that they stayed for multiple decades.

mathematics, English, drawing, and physical education, garnering knowledge and skills they could use in their own classrooms. Instructors such as Grace Spalding, Northern’s art teacher, and Wayne B. McClintock, who taught physical education and organized sporting events outside of class, earned such respect from students and fellow faculty and administration that they’re honored on campus even today in the names of the buildings that educate, house, and support current Northern students. Many of these early professors grew so fond of Northern that they stayed for multiple decades.

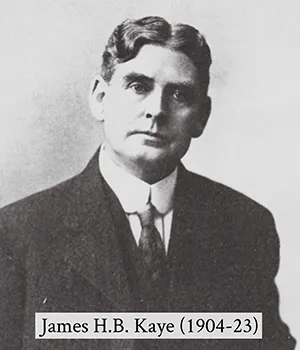

James H.B. Kaye (1904-1923)

2nd President of Northern Normal

The Best Students

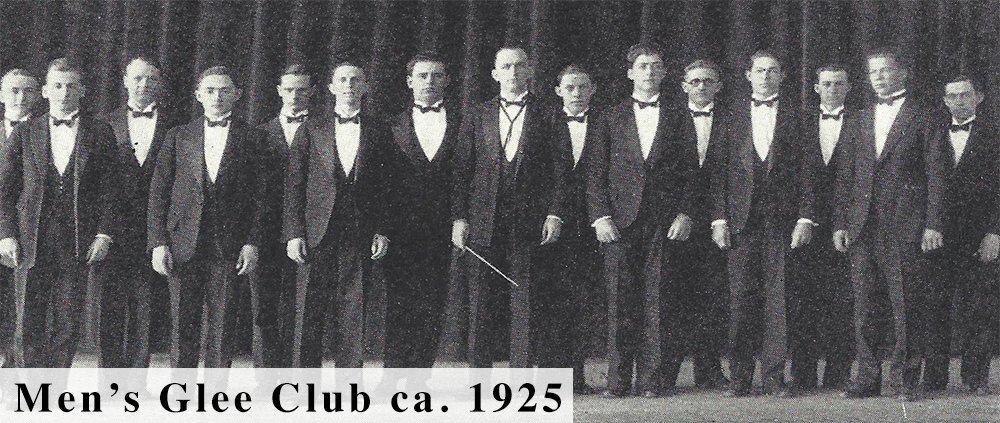

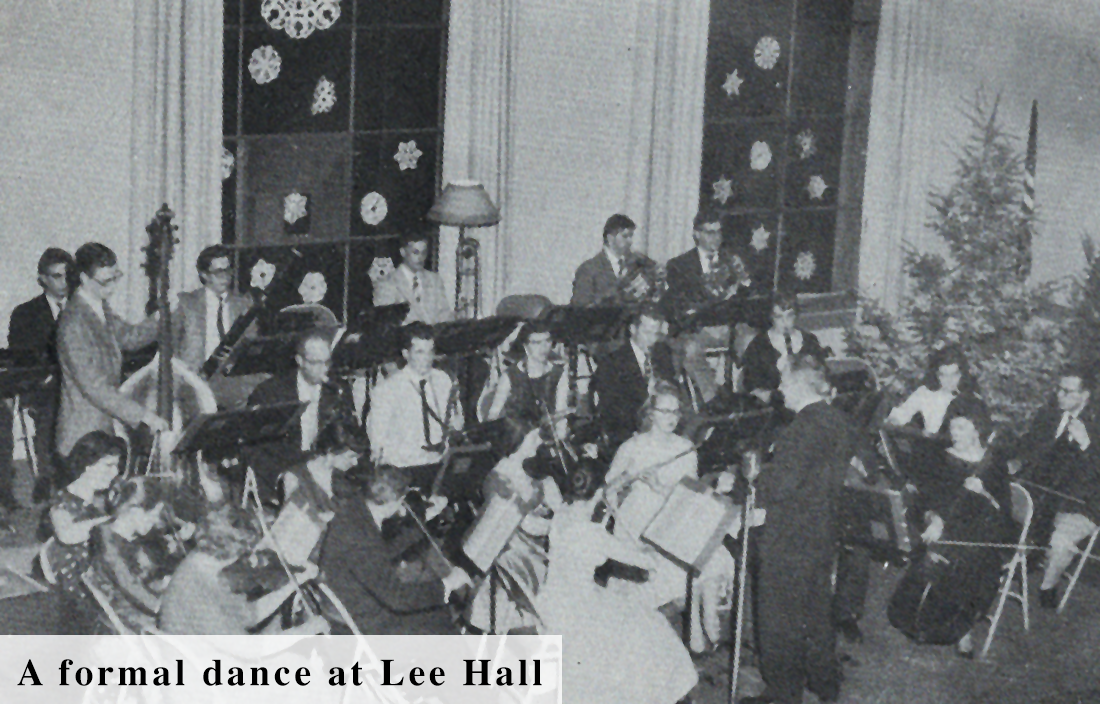

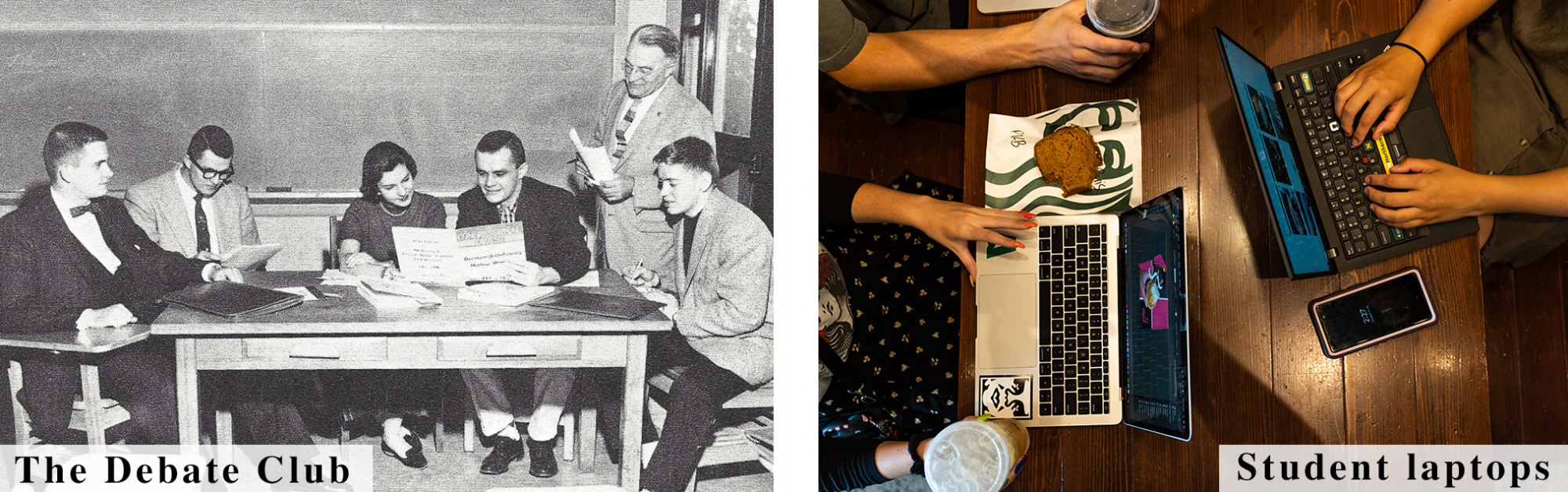

Outside of class, “normalites” attended social events like school dances and dinners, or joined literary societies or social sororities. There were assemblies in which students or broader community members shared their life experiences and debates in which students discussed topical issues like women’s suffrage. Creative students supplied theatrical and musical performances for the local community. Girls organized sports teams as early as 1909, though these were later discontinued before popping back up again in the latter half of the 20th century. Particularly after the First World War, more men came to Northern, and men’s sports clubs, and later teams, like football started as well. Early Presidents of the institution—such as Northern’s first, President Waldo—had high hopes not only for the intellectual development of Northern but for its cultural development as well. Despite its somewhat isolated locale, President Waldo thought of the world as cosmopolitan and ordered magazines in other languages for students to peruse. From its beginnings, Northern considered itself to have the same potential as any other post-secondary institution and demanded the best its students could give.

Although many of Northern’s early students came to classes in the summertime, year-round classes went on as well. A small women's dormitory existed on campus from 1900 to 1918, but between then and 1948, students utilized the local community for their housing. They rented rooms in local residents’ homes throughout the school year—as there were approximately 1,000 students in 1920, placing all of these students became a noteworthy challenge, as student representatives from Northern went around knocking on doors to ask if families had any bedrooms to spare. Gratefully, Yooper's hospitality meant that everyone managed to find a place to eat and sleep. In their surrogate homes, and in their classes and at school functions, students observed strict rules of conduct and dress, but as with most college students, they managed to enjoy themselves nonetheless.

Over the course of its early years, Northern Normal maintained a trajectory of slow and steady growth. It grew not only in population but in opportunity: the first Bachelor of Arts degree was awarded to a female student in 1920, and Northern became certified to grant Bachelor of Science degrees only a few years later. Those students who graduated from Northern’s program earned a reputation of being competent and well-trained teachers and didn’t struggle to find employment (if they weren’t employed already, as so many early students were). From its first graduating class of ~30 students educated in a back room of city hall to a growing campus bustling with student life, Northern Normal established itself as a fixture in the community.

Northern State Teachers College

As Northern’s size and impact grew, and Normal Schools began to phase out to usher in a new era of higher education in the United States, the Michigan State Legislature decided that Northern needed a new title: Northern State Teacher’s College. However, due to the broader social circumstances of the time, the institution lulled during this period (from 1923-42). Enrollment hovered around 500 for much of the 1920s, but Northern expanded its horizons both academically and in extracurricular activities. Of the students who attended, a greater portion began to travel up from Michigan’s Lower Peninsula and

As Northern’s size and impact grew, and Normal Schools began to phase out to usher in a new era of higher education in the United States, the Michigan State Legislature decided that Northern needed a new title: Northern State Teacher’s College. However, due to the broader social circumstances of the time, the institution lulled during this period (from 1923-42). Enrollment hovered around 500 for much of the 1920s, but Northern expanded its horizons both academically and in extracurricular activities. Of the students who attended, a greater portion began to travel up from Michigan’s Lower Peninsula and sought bachelor’s degrees rather than teaching certificates. Whereas many fields had started out with merely one instructor to teach them and represent the entire discipline, departments were born in which department heads could oversee multiple professors working in the same area of study. Professors at Northern became more likely to have obtained a terminal degree in their field and were generally well-respected in their fields. They also began to conduct research specific to the U.P., which served a substantial role in preserving the history and exploring the intricacies of this oft-overlooked region (and continues to do so today).

sought bachelor’s degrees rather than teaching certificates. Whereas many fields had started out with merely one instructor to teach them and represent the entire discipline, departments were born in which department heads could oversee multiple professors working in the same area of study. Professors at Northern became more likely to have obtained a terminal degree in their field and were generally well-respected in their fields. They also began to conduct research specific to the U.P., which served a substantial role in preserving the history and exploring the intricacies of this oft-overlooked region (and continues to do so today).

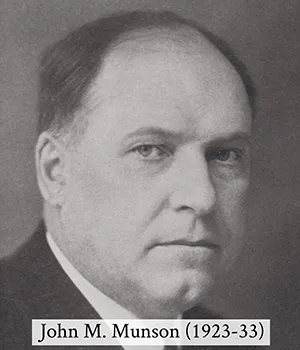

John M. Munson

1st President of Northern State Teacher's College

Great Depression Years

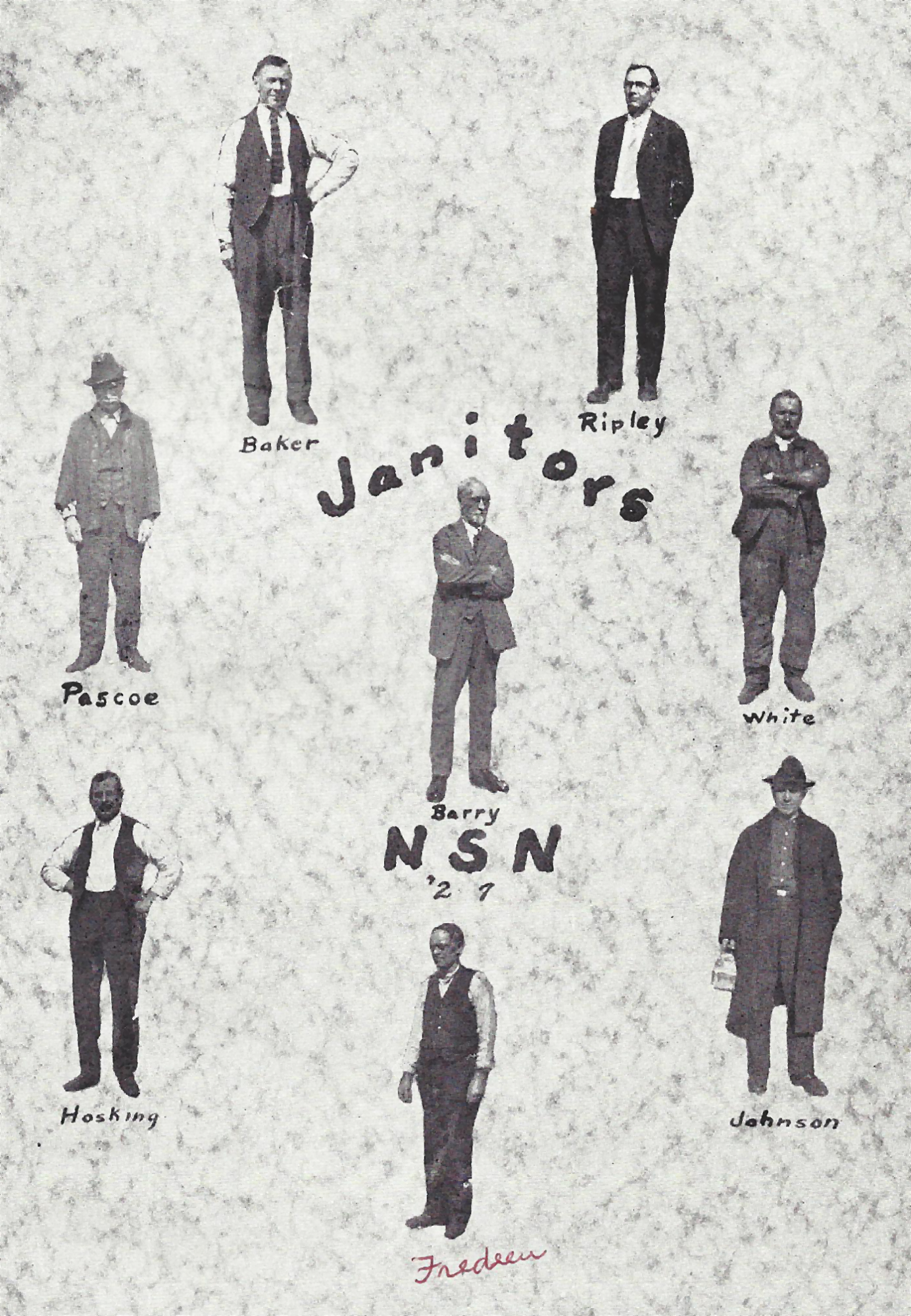

As the Roaring Twenties plummeted into the years of the Great Depression, post-secondary education became more tenuous for many students who relied on family support to live and study in Marquette. For those students determined to stay, their college experience often changed. If a student couldn’t afford room and board at a local house, they might try either to bring food from their homes, or to offer their labor to the family in exchange for discounted or free lodging. Unfortunately, the families boarding students also struggled during this time, so such an arrangement couldn’t work for everyone. Northern, for its part, began to allow students to work as janitors for the school in 1933, offering students a second avenue to earn the money required to fund their education. Though this time period presented great difficulty to individuals and families across the United States, Northern pressed on and didn’t lose hope for its future.

As the Roaring Twenties plummeted into the years of the Great Depression, post-secondary education became more tenuous for many students who relied on family support to live and study in Marquette. For those students determined to stay, their college experience often changed. If a student couldn’t afford room and board at a local house, they might try either to bring food from their homes, or to offer their labor to the family in exchange for discounted or free lodging. Unfortunately, the families boarding students also struggled during this time, so such an arrangement couldn’t work for everyone. Northern, for its part, began to allow students to work as janitors for the school in 1933, offering students a second avenue to earn the money required to fund their education. Though this time period presented great difficulty to individuals and families across the United States, Northern pressed on and didn’t lose hope for its future.

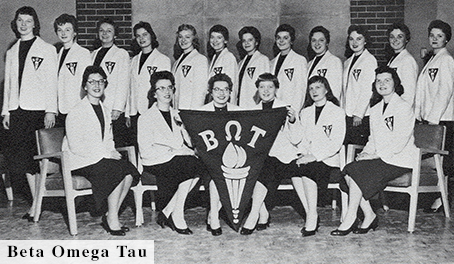

The students didn’t lose hope of having a memorable and enjoyable college experience, either. Students continued to host lively campus debates and other social functions to keep the campus vibrant, and many students joined social sororities or fraternities. Those organizations also began to incorporate a community-oriented mindset into their activities, and offered their time and effort to serve those who needed help surviving the Depression (and the community gave back by advocating that governmental entities continue to fund the college). Although Northern had celebrated a “homecoming” football game in 1924, Homecoming became an annual tradition starting in 1935, giving students a chance to celebrate their school spirit. Students might not have been able to host the fancy banquets of yesteryear due to a lack of discretional funds, but they made the most of their experience.

The students didn’t lose hope of having a memorable and enjoyable college experience, either. Students continued to host lively campus debates and other social functions to keep the campus vibrant, and many students joined social sororities or fraternities. Those organizations also began to incorporate a community-oriented mindset into their activities, and offered their time and effort to serve those who needed help surviving the Depression (and the community gave back by advocating that governmental entities continue to fund the college). Although Northern had celebrated a “homecoming” football game in 1924, Homecoming became an annual tradition starting in 1935, giving students a chance to celebrate their school spirit. Students might not have been able to host the fancy banquets of yesteryear due to a lack of discretional funds, but they made the most of their experience.

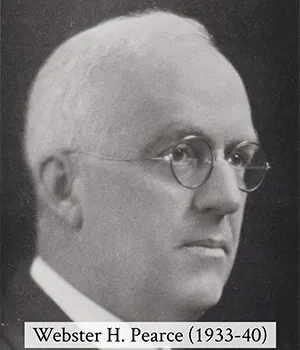

Webster H. Pearce

2nd President of Northern State Teacher's College

Early 20th Centruy Norms

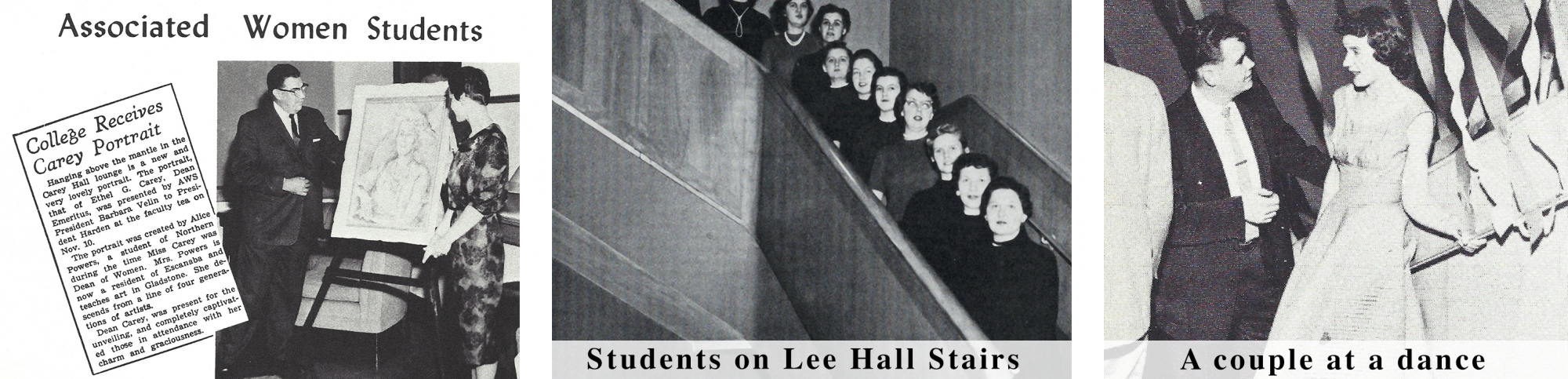

Of course, due to the social norms of the time, students weren’t afforded the same level of freedom in their activities as today’s college students. In the earlier decades of the 20th century, colleges were expected to act in loco parentis—in place of parents—for their students and were encouraged to strictly monitor the behavior of their students. Northern maintained fairly strict rules of etiquette and decorum both in-class and outside of it.There was even a Dean of Women—the most famous of which was Ethel Carey—charged with the task of maintaining proper character development among the female students (this took the form of banning smoking and dancing too close to partners at school functions, among other things). To be fair, there was a Dean of Men for a time as well, though that position receives far less attention in Northern’s lore.

Of course, due to the social norms of the time, students weren’t afforded the same level of freedom in their activities as today’s college students. In the earlier decades of the 20th century, colleges were expected to act in loco parentis—in place of parents—for their students and were encouraged to strictly monitor the behavior of their students. Northern maintained fairly strict rules of etiquette and decorum both in-class and outside of it.There was even a Dean of Women—the most famous of which was Ethel Carey—charged with the task of maintaining proper character development among the female students (this took the form of banning smoking and dancing too close to partners at school functions, among other things). To be fair, there was a Dean of Men for a time as well, though that position receives far less attention in Northern’s lore.

Henry A. Tape

3rd President of Northern State Teacher's College

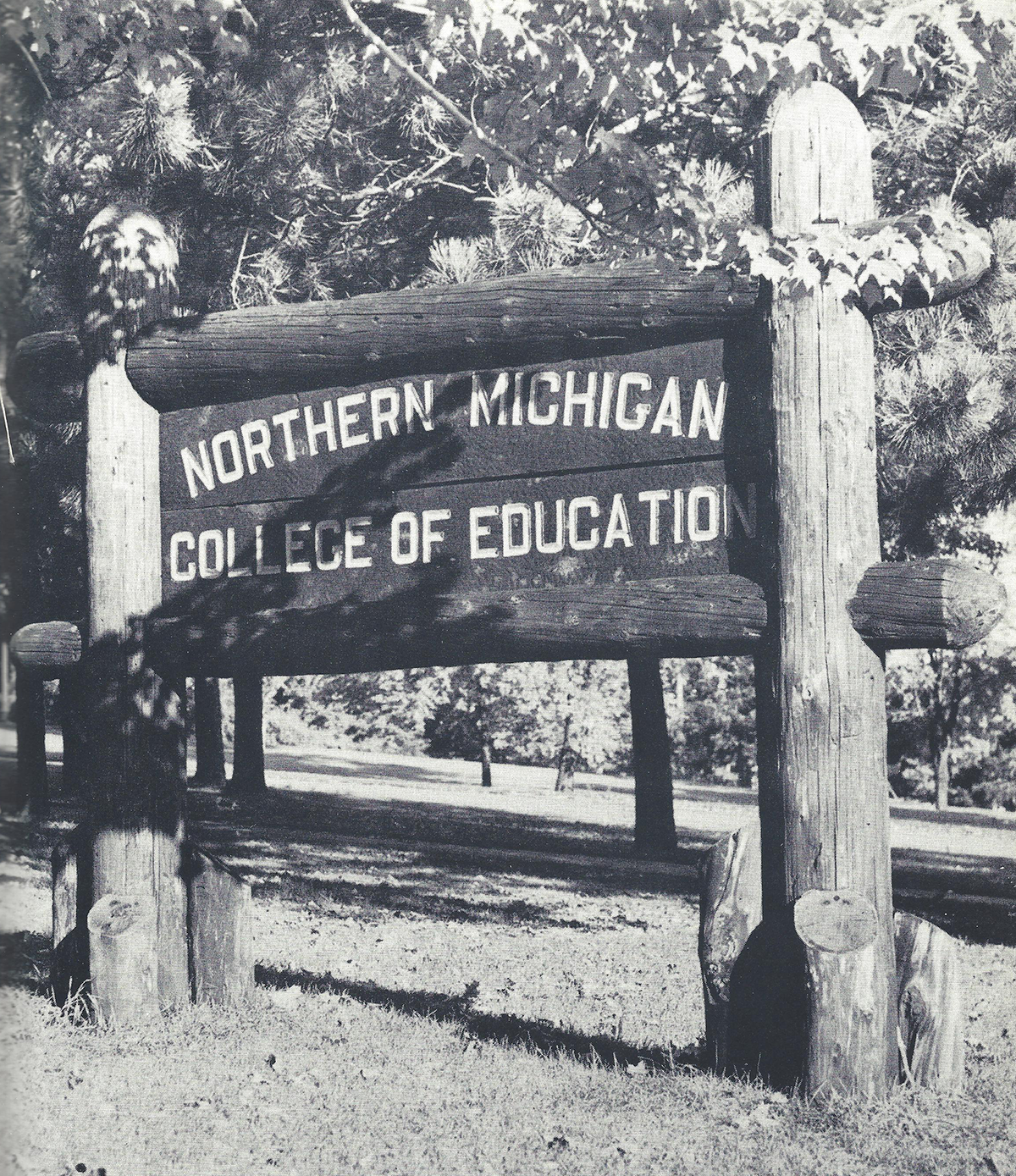

Northern Michigan College of Education

Northern received its third name change in 1942, around the end of the Second World War, because the curriculum was expanding so far beyond education alone. However, the early 1940s demanded that creating teachers remain the primary goal—Michigan was facing a shortage of them, but the war had lowered Northern’s enrollment to less than 250 students, almost all of them women. For a time, Northern even brought back its limited teaching certificate training to fill the need. Campus life was more muted because the student population had dipped so much and become so homogenous: most of the male students had become involved in the war effort.

Northern received its third name change in 1942, around the end of the Second World War, because the curriculum was expanding so far beyond education alone. However, the early 1940s demanded that creating teachers remain the primary goal—Michigan was facing a shortage of them, but the war had lowered Northern’s enrollment to less than 250 students, almost all of them women. For a time, Northern even brought back its limited teaching certificate training to fill the need. Campus life was more muted because the student population had dipped so much and become so homogenous: most of the male students had become involved in the war effort.

The conclusion of the Second  World War brought about a very different era for higher education in the United States. As both a reward and incentive for military service, the United States Government passed the G.I. Bill, which afforded tuition-free college education to veterans. Given that there were so many veterans at the time, it brought about a boom in the number of individuals enrolled at colleges and universities across the country. Northern welcomed the return of the male half of its student population. No longer under the stress of a severe teacher shortage, Northern expanded its educational catalogue, and began to admit a substantial portion of graduate students in addition to undergrads.

World War brought about a very different era for higher education in the United States. As both a reward and incentive for military service, the United States Government passed the G.I. Bill, which afforded tuition-free college education to veterans. Given that there were so many veterans at the time, it brought about a boom in the number of individuals enrolled at colleges and universities across the country. Northern welcomed the return of the male half of its student population. No longer under the stress of a severe teacher shortage, Northern expanded its educational catalogue, and began to admit a substantial portion of graduate students in addition to undergrads.

Edgar L. Harden

1st President of Northern Michigan College of Education

Expanding Physically

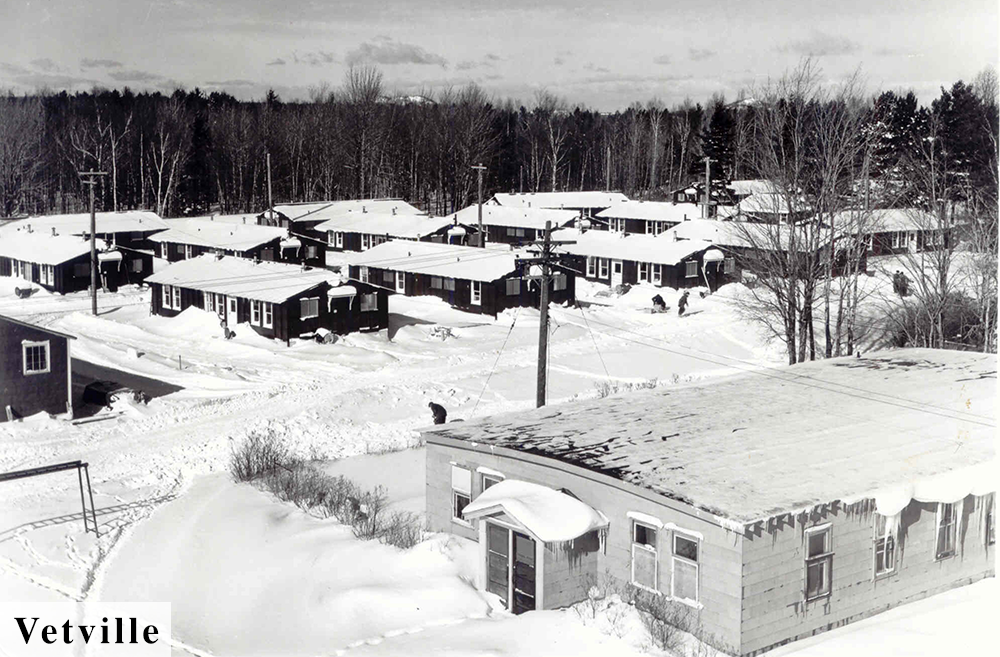

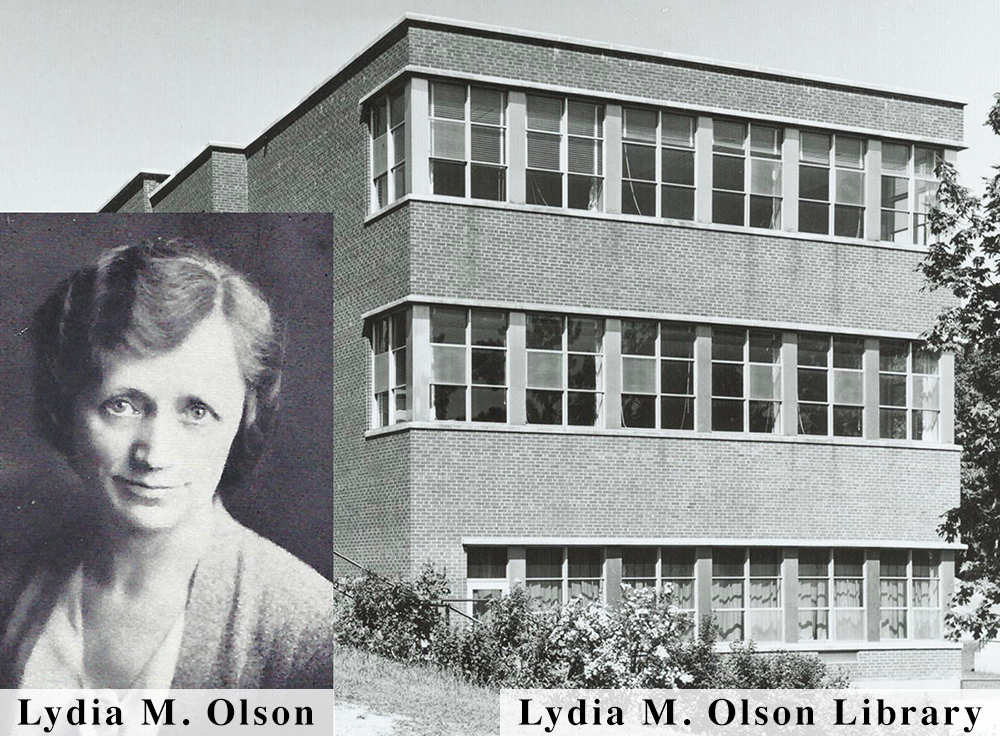

It expanded physically, too—the state approved construction of the first female dormitory and a student union--both of which were finished in 1948--the library was built and dedicated to Lydia Olson, the President’s House was erected, and the men got their dormitory—Spooner Hall—in 1955. Married students who didn’t quite fit into either dormitory offering lived in what was called “Vetville”, a series of converted army barracks reserved for the older, married, and mostly-veteran students. Incoming students were required to live on campus, affording a level of both physical and social closeness that Northern students potentially lacked in earlier years.

It expanded physically, too—the state approved construction of the first female dormitory and a student union--both of which were finished in 1948--the library was built and dedicated to Lydia Olson, the President’s House was erected, and the men got their dormitory—Spooner Hall—in 1955. Married students who didn’t quite fit into either dormitory offering lived in what was called “Vetville”, a series of converted army barracks reserved for the older, married, and mostly-veteran students. Incoming students were required to live on campus, affording a level of both physical and social closeness that Northern students potentially lacked in earlier years.

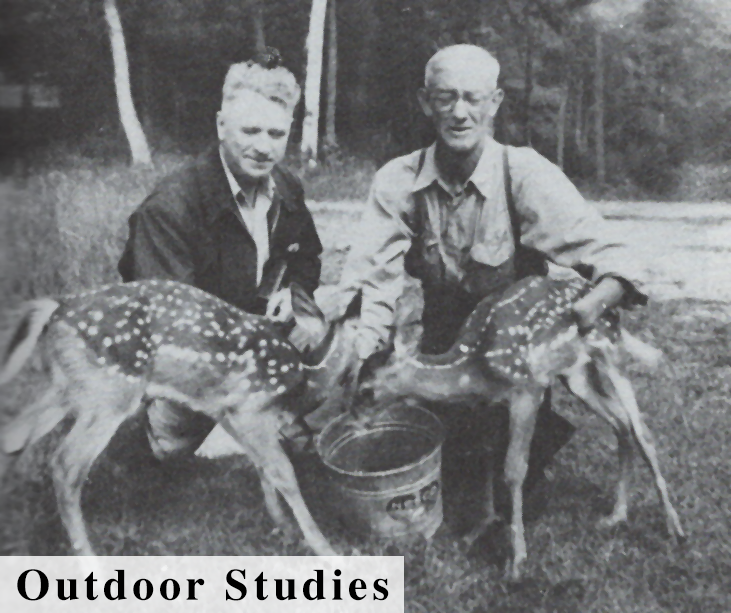

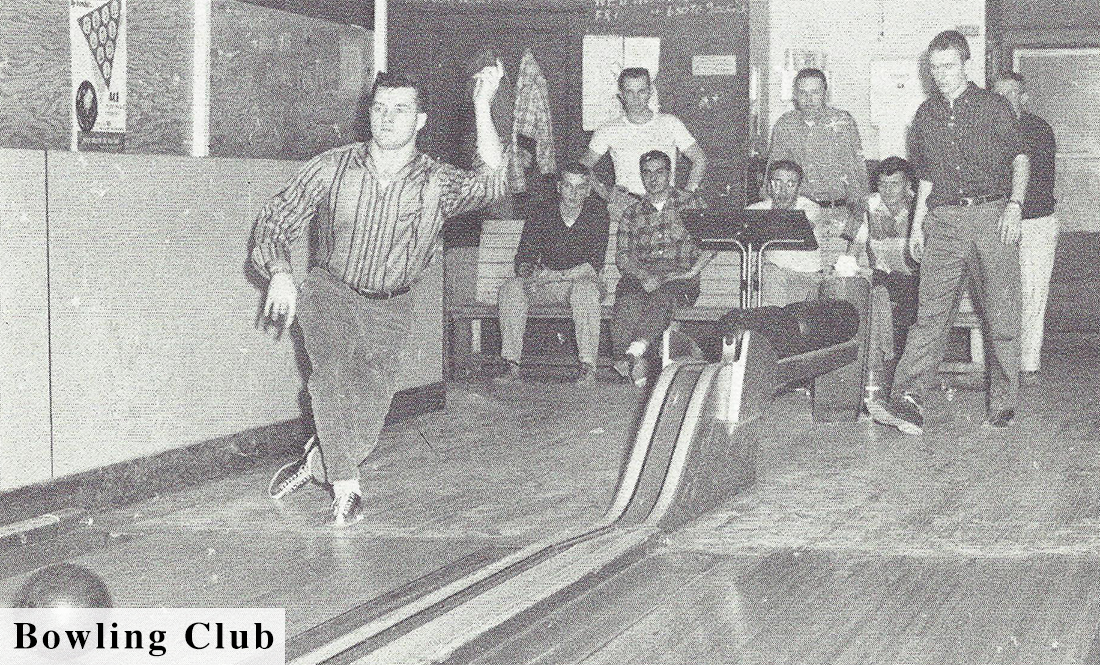

Perhaps thanks in part to the emergence of on-campus living, social life both on- and off-campus flourished. Still, it remained centered on the tight community that Northern had built as a small college in a rural part of the country. Faculty women would host female students in their homes for dinner, and fraternities and sororities continued to prosper for both their pledges and the campus on the whole, as they hosted many all-campus events. Though many students involved  themselves on campus through student organizations, students continued to pursue their own hobbies in their free time—some of which might be very familiar to today’s Northern students. In a student survey conducted in 1945, Northern Student’s recorded their favorite pastimes as “hunting for wild game or mushrooms, outdoor sports, bowling, bridge, and knitting.” Northern continued its community involvement by allowing its space and resources to be used by the local community by hosting conferences for high schoolers and GED tests and psychological screenings for children; in many cases, such services were the only ones of their kind offered in the Upper Peninsula.

themselves on campus through student organizations, students continued to pursue their own hobbies in their free time—some of which might be very familiar to today’s Northern students. In a student survey conducted in 1945, Northern Student’s recorded their favorite pastimes as “hunting for wild game or mushrooms, outdoor sports, bowling, bridge, and knitting.” Northern continued its community involvement by allowing its space and resources to be used by the local community by hosting conferences for high schoolers and GED tests and psychological screenings for children; in many cases, such services were the only ones of their kind offered in the Upper Peninsula.

Ogden E. Johnson

2nd President of Northern Michigan College of Education

Tight Community

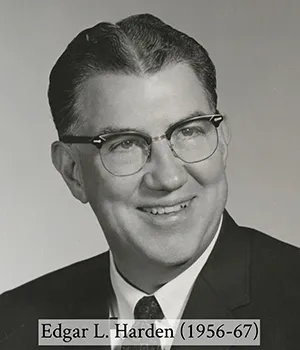

While campus life blossomed during the 1940s, the end of the Second World War also brought about more challenging circumstances for Northern’s institutional future. Upper Peninsula mines were declining in their valuations and beginning to discuss closure, and economic opportunity in more populated parts of the country called many people to emigrate from the U.P. to elsewhere. The Upper Peninsula had fallen from its heyday of bustling mining and logging bringing thousands of immigrant families to the area. The State began to doubt whether Northern was even necessary, as enrollment remained low in comparison to Michigan’s other State Schools. Then, against the odds, came President Harden.

While campus life blossomed during the 1940s, the end of the Second World War also brought about more challenging circumstances for Northern’s institutional future. Upper Peninsula mines were declining in their valuations and beginning to discuss closure, and economic opportunity in more populated parts of the country called many people to emigrate from the U.P. to elsewhere. The Upper Peninsula had fallen from its heyday of bustling mining and logging bringing thousands of immigrant families to the area. The State began to doubt whether Northern was even necessary, as enrollment remained low in comparison to Michigan’s other State Schools. Then, against the odds, came President Harden.

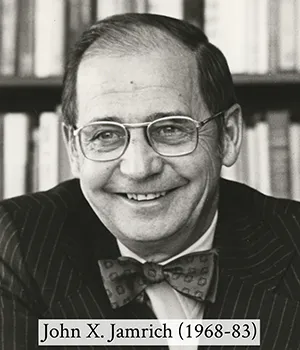

John X. Jamrich

1st President of Northern Michigan University

Northern Michigan University

President Harden served Northern from 1956-1967. Despite the growth gained by the G.I. Bill, President Harden had a vision for more. In the midst of a declining regional population and the threat of decreased funding (or even closure), President Harden set his sights on enrollment. Through his efforts (and the help of the Mackinac Bridge opening in the late 1950s), Northern Michigan grew from 888 to 7085 students from 1955 to 1967 and was officially granted its final name change to Northern Michigan University in 1963.

President Harden served Northern from 1956-1967. Despite the growth gained by the G.I. Bill, President Harden had a vision for more. In the midst of a declining regional population and the threat of decreased funding (or even closure), President Harden set his sights on enrollment. Through his efforts (and the help of the Mackinac Bridge opening in the late 1950s), Northern Michigan grew from 888 to 7085 students from 1955 to 1967 and was officially granted its final name change to Northern Michigan University in 1963.

Part of Northern’s growth derived from President Harden’s “right to try” policy, in which he argued that any student who wanted to obtain a college education should have the right to do so. This meant that Northern maintained completely open admission policies throughout his tenure, at a time when many comparable institutions had tightened their admission standards. Consequently, many students who came to Northern with subpar academic records left before receiving their degrees, but this policy also allowed individuals like Dr. John Beaumier (an accomplished surgeon and the benefactor of the Beaumier U.P. Heritage Center) who might not have been given a chance elsewhere to prove their academic potential.

admission policies throughout his tenure, at a time when many comparable institutions had tightened their admission standards. Consequently, many students who came to Northern with subpar academic records left before receiving their degrees, but this policy also allowed individuals like Dr. John Beaumier (an accomplished surgeon and the benefactor of the Beaumier U.P. Heritage Center) who might not have been given a chance elsewhere to prove their academic potential.

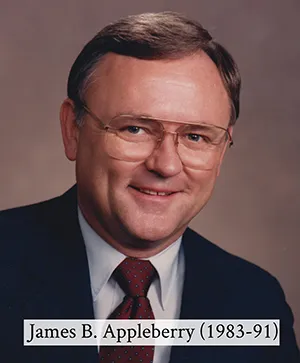

James B. Appleberry

2nd President of Northern Michigan University

Rapid Enrollment and Infrastructure

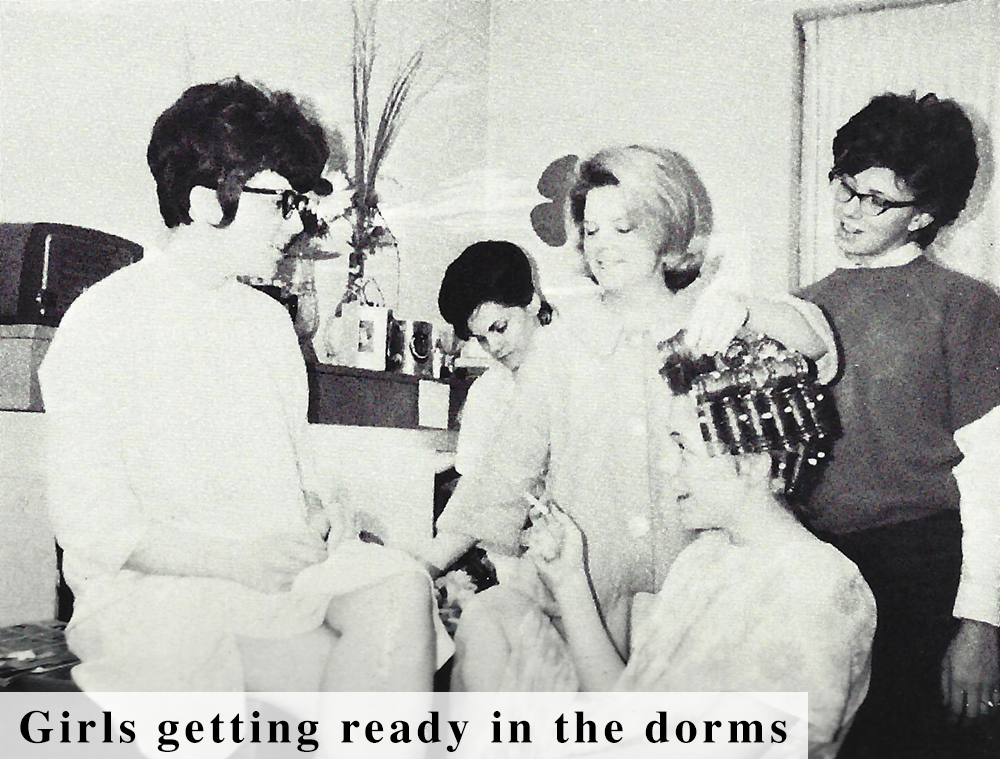

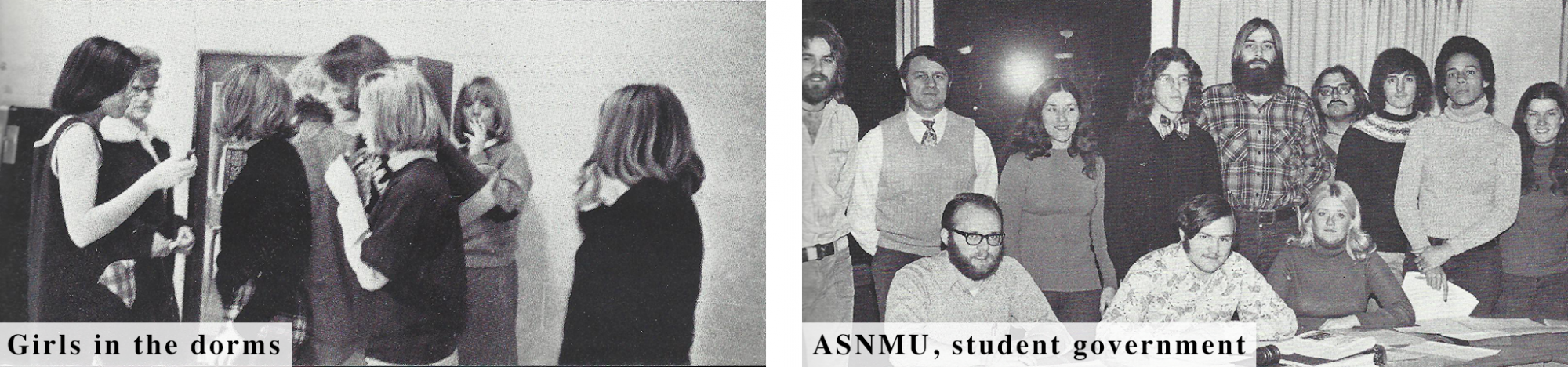

Such a rapid enrollment increase certainly came with its positives for the University, as discussions of closure ceased and discussions of new opportunities began. However, it also came with some challenges, as Northern’s infrastructure wasn’t necessarily prepared for so many students at once. Dorm rooms meant for two students often ended up with three or four, and the students populating them had far less favorable feelings toward the in loco parentis policies of the past. Students began to see themselves as active participants in the shaping of University policies and practices, and used that self-awareness to begin to demand better and more of their institution.

Such a rapid enrollment increase certainly came with its positives for the University, as discussions of closure ceased and discussions of new opportunities began. However, it also came with some challenges, as Northern’s infrastructure wasn’t necessarily prepared for so many students at once. Dorm rooms meant for two students often ended up with three or four, and the students populating them had far less favorable feelings toward the in loco parentis policies of the past. Students began to see themselves as active participants in the shaping of University policies and practices, and used that self-awareness to begin to demand better and more of their institution.

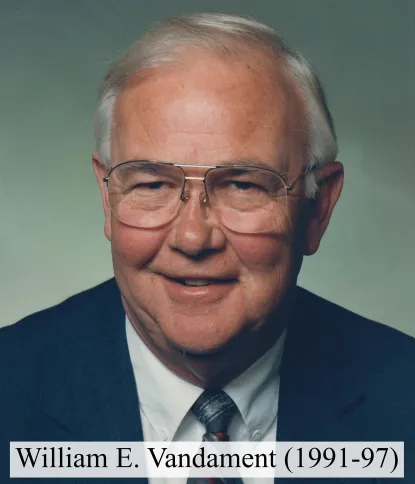

William E. Vandament

3rd President of Northern Michigan University

Disagreement During Growth

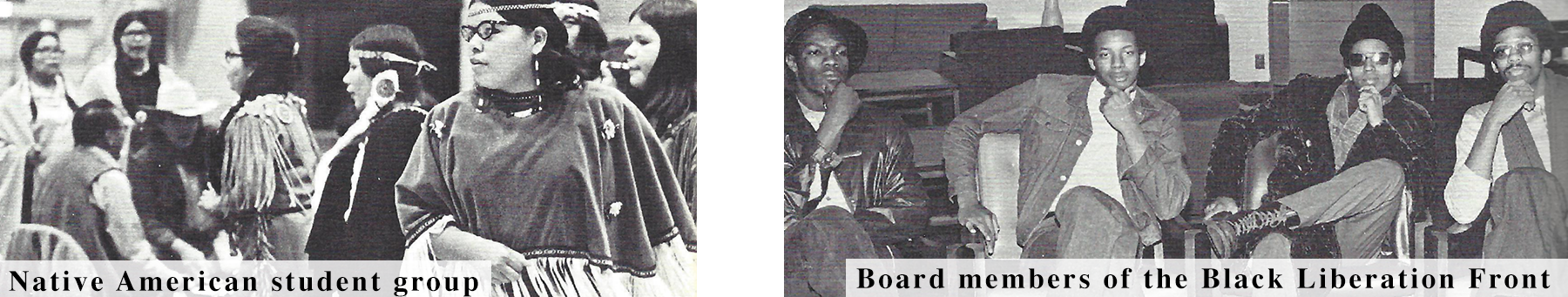

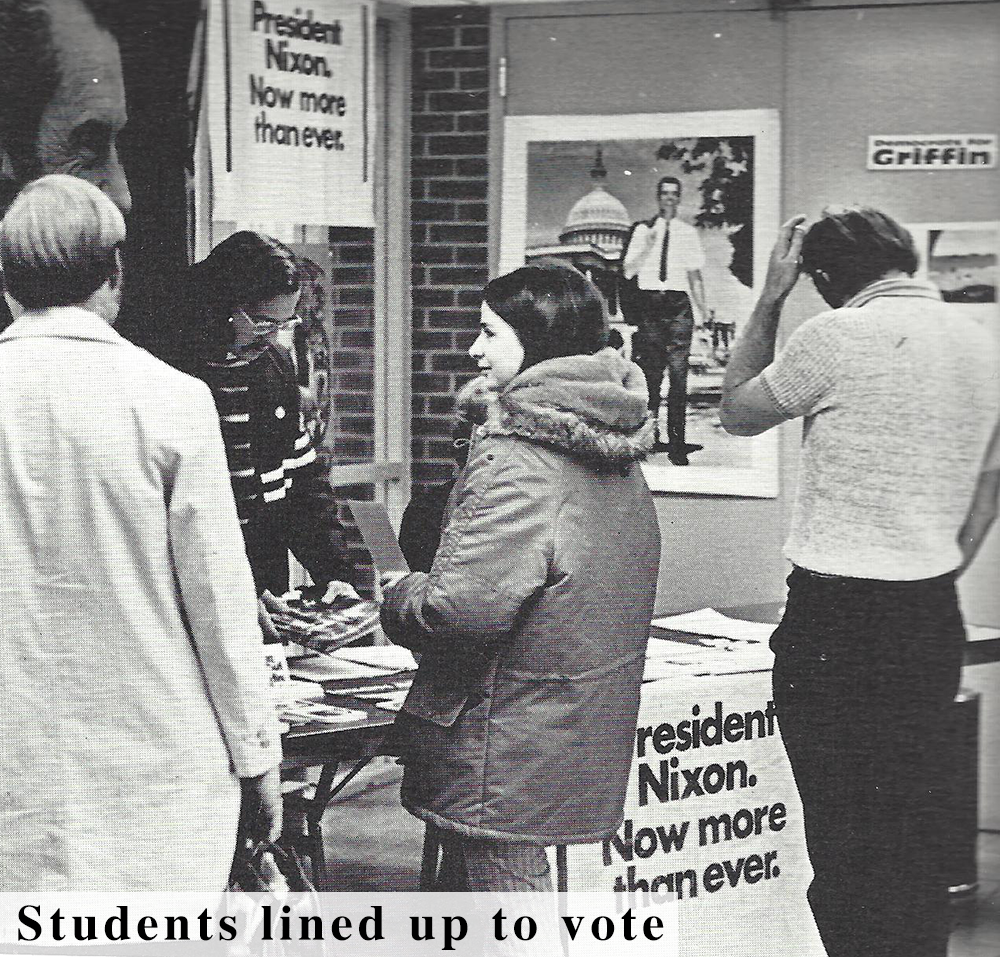

A heightened sense of student agency keeps a University alive and accountable, which has the opportunity both to help a university grow and to incite some disagreement during that growth period. As such, the decade after President Harden stepped down from his position came with some controversy for NMU. The new President—John X. Jamrich— had to navigate student Vietnam War protests, the McClellan controversy (started during President Harden's tenure, in which a professor was unjustly fired for informing the community about their rights in the face of NMU’s campus expansion plan to use the land on which their homes stood) and demands for greater equity for Black students. Students turned their discontent into action, staging sit-ins and marches to make their voices heard. Increased enrollment from the Harden period meant increased diversity, and it was no longer the case that a vast majority of students came from the Upper Peninsula. Enrollment of American Indian students from surrounding communities increased as well, and Native students on campus started Nishnawbe News, one of the only publications focused on raising the voices and experiences of American Indian people at that time. Increased diversity certainly exposed Northern’s shortfalls in creating a truly inclusive community, but it also came with opportunities for new perspectives; Black fraternities and student organizations sprung up on campus, the seed that would become the Center for Native American Studies was planted, and Northern undoubtedly grew as a result.

A heightened sense of student agency keeps a University alive and accountable, which has the opportunity both to help a university grow and to incite some disagreement during that growth period. As such, the decade after President Harden stepped down from his position came with some controversy for NMU. The new President—John X. Jamrich— had to navigate student Vietnam War protests, the McClellan controversy (started during President Harden's tenure, in which a professor was unjustly fired for informing the community about their rights in the face of NMU’s campus expansion plan to use the land on which their homes stood) and demands for greater equity for Black students. Students turned their discontent into action, staging sit-ins and marches to make their voices heard. Increased enrollment from the Harden period meant increased diversity, and it was no longer the case that a vast majority of students came from the Upper Peninsula. Enrollment of American Indian students from surrounding communities increased as well, and Native students on campus started Nishnawbe News, one of the only publications focused on raising the voices and experiences of American Indian people at that time. Increased diversity certainly exposed Northern’s shortfalls in creating a truly inclusive community, but it also came with opportunities for new perspectives; Black fraternities and student organizations sprung up on campus, the seed that would become the Center for Native American Studies was planted, and Northern undoubtedly grew as a result.

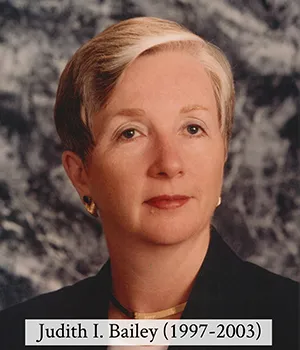

Judith I. Bailey

4th President of Northern Michigan University

Expanding Our Role

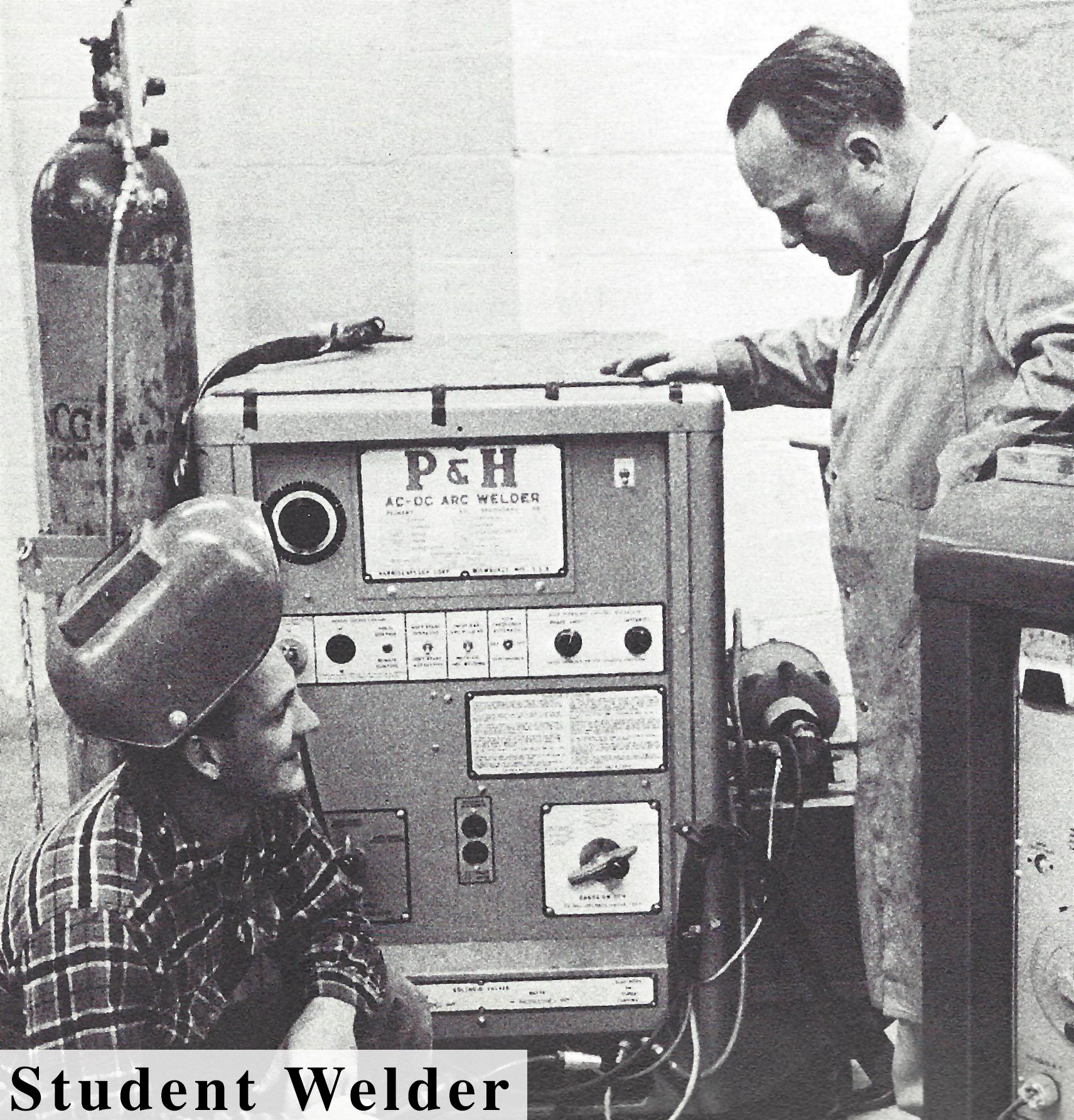

A portion of NMU's increasing diversity also arose from its efforts to expand its role as a community college. While Northern started off mostly granting teachers licenses as a two-year program, it has primarily granted bachelor's degrees throughout its history. The lack of comparable educational opportunities for Marquette and Alger counties granted Northern an official designation by the Michigan Department of Education as having a community college function in 1969. Put more plainly, this designation means that Northern has put an emphasis on vocational training, continuing education, and associate degree programs to an extent that most other four-year universities wouldn't. This emphasis took form in a variety of initiatives at Northern, from the formation of Northern's Job Corps Center for Women in 1966 and its Area Training Center in 1962 to the building of the Jacobetti Center in 1980. The Job Corps Center provided skill training for young women for fields such as data processing, graphic arts, practical nursing, and secretarial work. These women came from all over the country. Unfortunately, budget cuts from the federal government led to the center's closure in 1969. The Training Center offered vocational training to lower-income individuals in the U.P., and eventually evolved into the NMU Skills Center, offering classes for those pursuing an associate's degree as well as to some high school students. The Skills Center later became the Jacobetti Center.

A portion of NMU's increasing diversity also arose from its efforts to expand its role as a community college. While Northern started off mostly granting teachers licenses as a two-year program, it has primarily granted bachelor's degrees throughout its history. The lack of comparable educational opportunities for Marquette and Alger counties granted Northern an official designation by the Michigan Department of Education as having a community college function in 1969. Put more plainly, this designation means that Northern has put an emphasis on vocational training, continuing education, and associate degree programs to an extent that most other four-year universities wouldn't. This emphasis took form in a variety of initiatives at Northern, from the formation of Northern's Job Corps Center for Women in 1966 and its Area Training Center in 1962 to the building of the Jacobetti Center in 1980. The Job Corps Center provided skill training for young women for fields such as data processing, graphic arts, practical nursing, and secretarial work. These women came from all over the country. Unfortunately, budget cuts from the federal government led to the center's closure in 1969. The Training Center offered vocational training to lower-income individuals in the U.P., and eventually evolved into the NMU Skills Center, offering classes for those pursuing an associate's degree as well as to some high school students. The Skills Center later became the Jacobetti Center.

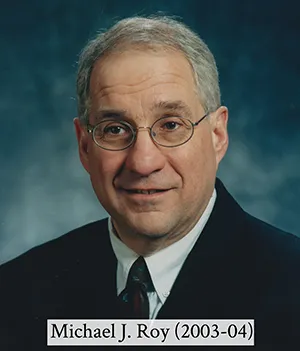

Michael J. Roy

5th President of Northern Michigan University

Intellectual and Athletic Growth

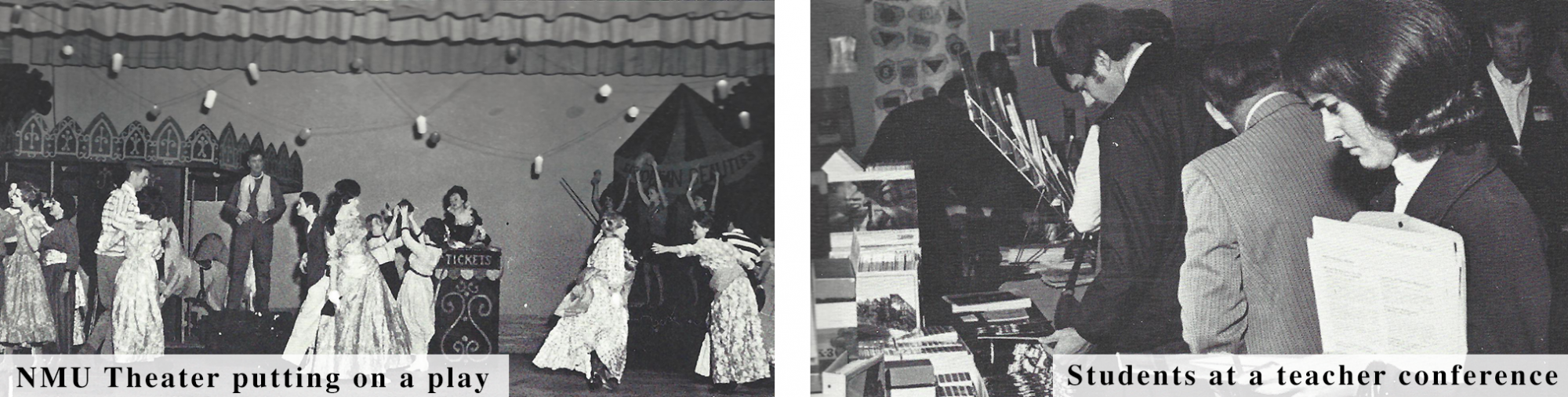

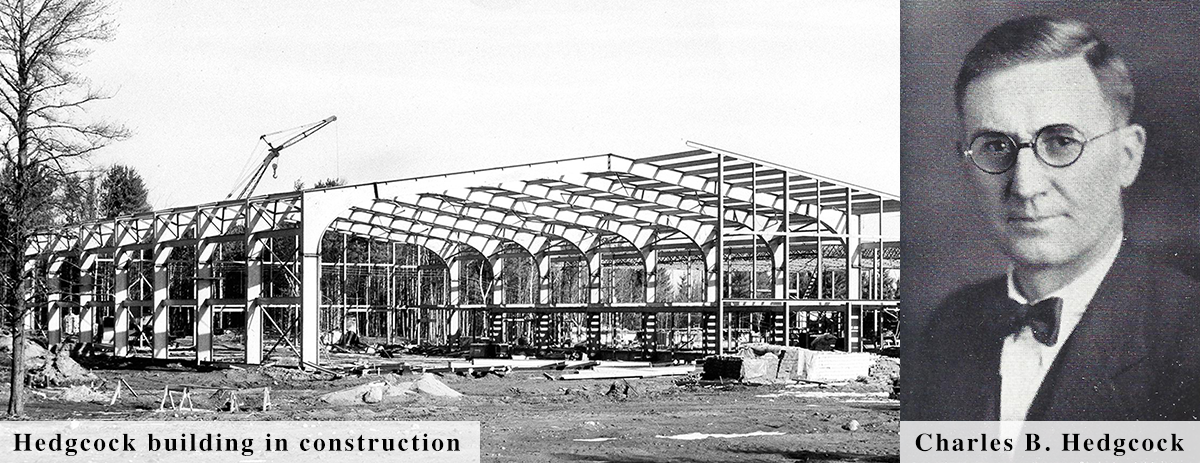

The University had returned to humbler rates of increased enrollment during the Jamrich Presidency, but maintained its intellectual growth by continuing to add new programs, research centers, and diverse opportunities for its students. Great professors who had spent decades teaching Northern students began to retire, marshalling in a new cohort of faculty; those great professors—from the whole of Northern’s history—can still be recognized in the names of buildings like Forest Roberts Theater, the Hedgcock Building, or Magers Hall. Outside of classes, NMU athletics succeeded, culminating in the 1975 NCAA Division II Football Championship, from which the NMU team came back after losing every single game in the 1974 season. Athletics have played a key role in shaping student extracurricular activity for much of its history, especially as newer sports like hockey and Nordic skiing gained traction on campus.

The University had returned to humbler rates of increased enrollment during the Jamrich Presidency, but maintained its intellectual growth by continuing to add new programs, research centers, and diverse opportunities for its students. Great professors who had spent decades teaching Northern students began to retire, marshalling in a new cohort of faculty; those great professors—from the whole of Northern’s history—can still be recognized in the names of buildings like Forest Roberts Theater, the Hedgcock Building, or Magers Hall. Outside of classes, NMU athletics succeeded, culminating in the 1975 NCAA Division II Football Championship, from which the NMU team came back after losing every single game in the 1974 season. Athletics have played a key role in shaping student extracurricular activity for much of its history, especially as newer sports like hockey and Nordic skiing gained traction on campus.

As evidenced in much of Northern’s communication materials, the only constant in its institutional history has been change; the latter decades of the 20th century—after President Jamrich left office in 1983—were no exception to this. Northern reached an enrollment high point in 1980 when 9,376 students enrolled for the fall semester, but the rest of the 1980s saw an enrollment drop. As a result, President Appleberry (who served from 1983-1991) decided to move away from President Harden’s “right-to-try” policy by tightening admissions standards. Northern had become known as somewhat of a party school during the 1970s, and apocryphal histories love to bring up Northern’s spot on Playboy Magazine’s “Top 10 Party Schools” list (although extensive research has found the designation to be an urban legend). Whether due to this reputation, or of the difficulty to attract top students to a little-known school that accepted anyone who applied, he felt that Northern’s reputation had fallen. In response, he decided it needed a stronger emphasis on the intellectual rigor of its programs in order to attract the most talented students it could find. His perspective likely had some merit, because enrollment actually increased with the tighter admissions standards.

As evidenced in much of Northern’s communication materials, the only constant in its institutional history has been change; the latter decades of the 20th century—after President Jamrich left office in 1983—were no exception to this. Northern reached an enrollment high point in 1980 when 9,376 students enrolled for the fall semester, but the rest of the 1980s saw an enrollment drop. As a result, President Appleberry (who served from 1983-1991) decided to move away from President Harden’s “right-to-try” policy by tightening admissions standards. Northern had become known as somewhat of a party school during the 1970s, and apocryphal histories love to bring up Northern’s spot on Playboy Magazine’s “Top 10 Party Schools” list (although extensive research has found the designation to be an urban legend). Whether due to this reputation, or of the difficulty to attract top students to a little-known school that accepted anyone who applied, he felt that Northern’s reputation had fallen. In response, he decided it needed a stronger emphasis on the intellectual rigor of its programs in order to attract the most talented students it could find. His perspective likely had some merit, because enrollment actually increased with the tighter admissions standards.

Leslie E. Wong

6th President of Northern Michigan University

Academic Sphere Extending

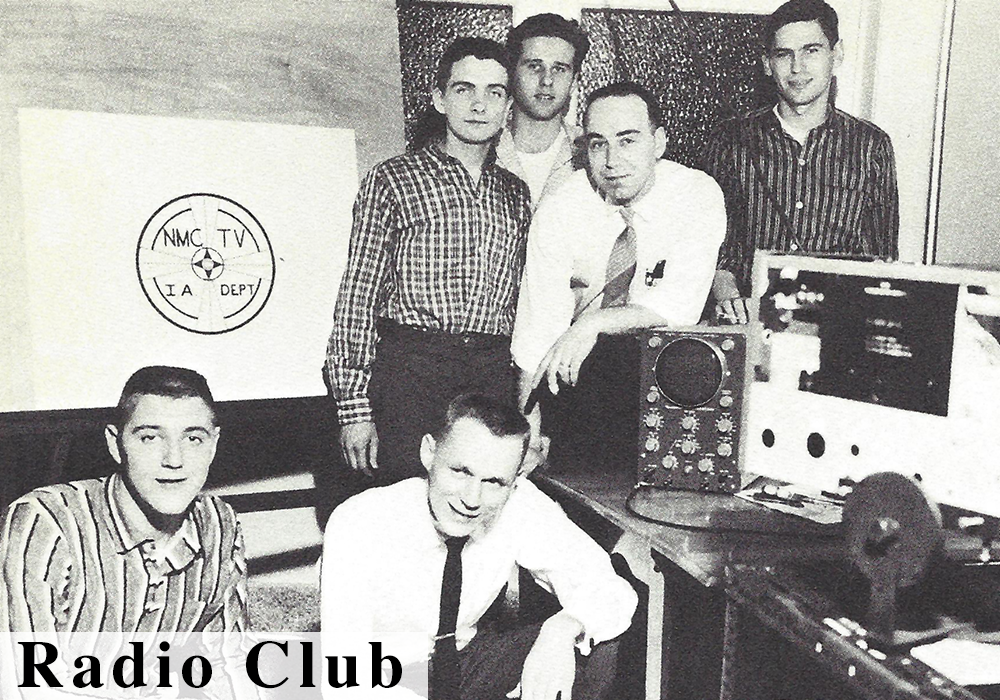

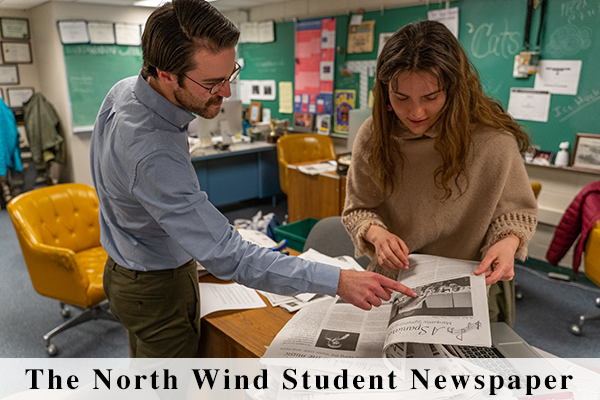

At the same time that Northern continued to grapple with its intellectual identity and recruitment strategies, its impact outside of the academic sphere began to extend both in its offerings and in the range of people they reached. Northern established both its student-run radio station and student-run newspaper (which had been under the administration and therefore limited in its scope for the years before it became

At the same time that Northern continued to grapple with its intellectual identity and recruitment strategies, its impact outside of the academic sphere began to extend both in its offerings and in the range of people they reached. Northern established both its student-run radio station and student-run newspaper (which had been under the administration and therefore limited in its scope for the years before it became  independent). In addition, Northern created a public television station to serve much of the U.P. and create content specifically for Yoopers. It continued to host both high school and academic conferences and to supply musical and theatrical performances for the community at large. As those who first lobbied the state legislature for its construction knew, Northern represented much more than just a school for the Marquette community.

independent). In addition, Northern created a public television station to serve much of the U.P. and create content specifically for Yoopers. It continued to host both high school and academic conferences and to supply musical and theatrical performances for the community at large. As those who first lobbied the state legislature for its construction knew, Northern represented much more than just a school for the Marquette community.

David S. Haynes

7th President of Northern Michigan University

Community and Campus Growth

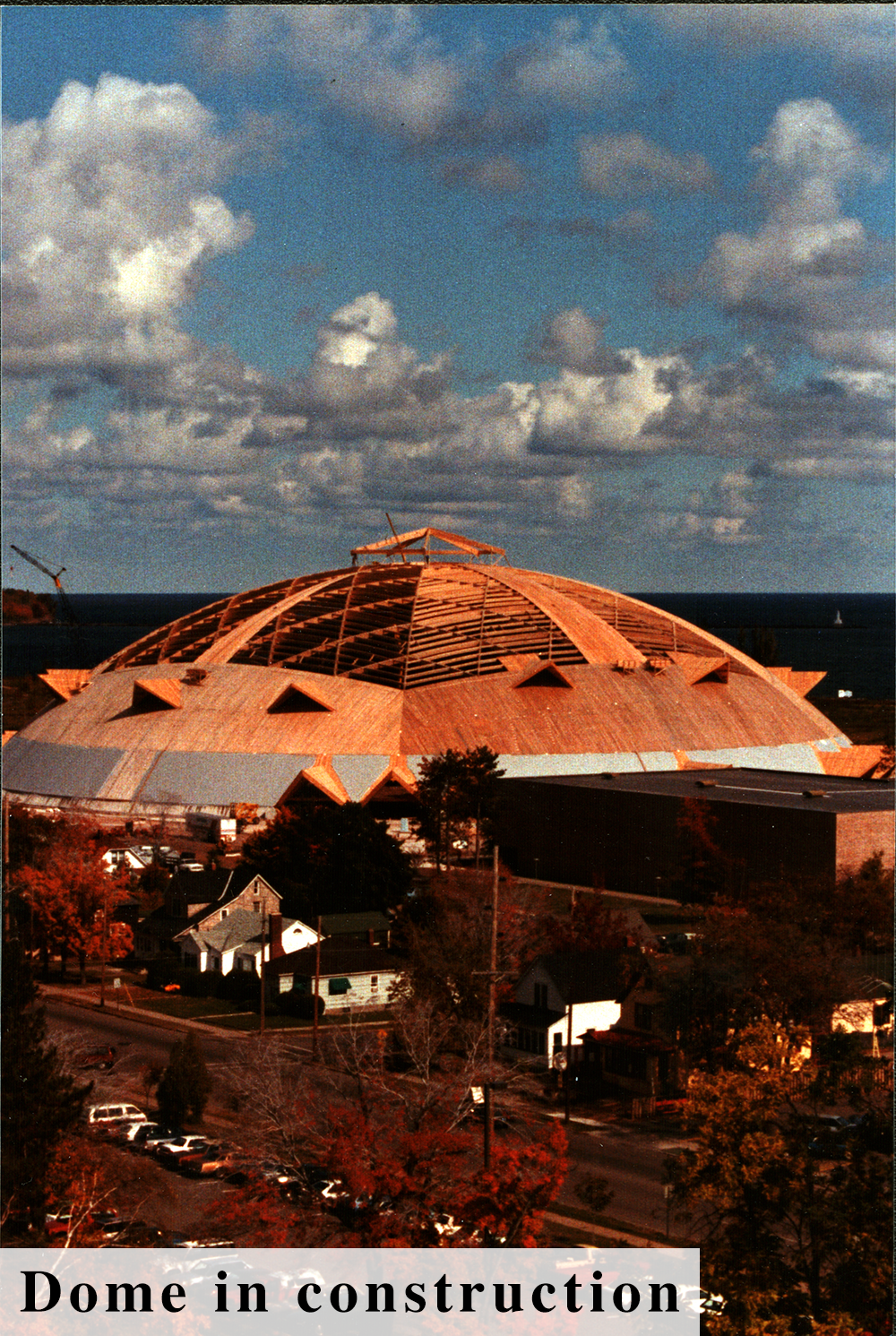

While its community impression grew, so too did the physical campus. The 1990s saw the building of the Superior Dome, and 53 other construction, expansion, and renovation projects during the tenure of President Vandament. NMU then made a significant leap in its history by inaugurating its first female president—Judith Bailey—in 1997, who served until 2003. Around this time, Northern also established its forward-thinking ThinkPad program, in which each student receives a laptop for educational use upon arriving on campus. Enrollment remained consistently in the 7,000-9,000 range, and many of the traditions started so many years ago—like homecoming, or the Brule Run, or student organizations serving the Marquette community—continued in earnest.

While its community impression grew, so too did the physical campus. The 1990s saw the building of the Superior Dome, and 53 other construction, expansion, and renovation projects during the tenure of President Vandament. NMU then made a significant leap in its history by inaugurating its first female president—Judith Bailey—in 1997, who served until 2003. Around this time, Northern also established its forward-thinking ThinkPad program, in which each student receives a laptop for educational use upon arriving on campus. Enrollment remained consistently in the 7,000-9,000 range, and many of the traditions started so many years ago—like homecoming, or the Brule Run, or student organizations serving the Marquette community—continued in earnest.

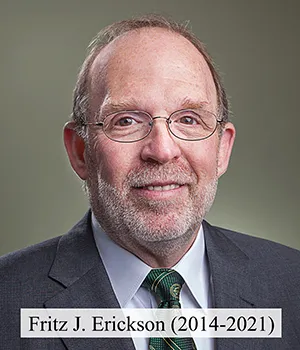

Fritz J. Erickson

8th President of Northern Michigan University

Its Heart will Endure

Northern has changed dramatically—both intellectually and physically—from its humble beginnings as a teacher training outpost for U.P. teachers. Today, even fairly recent alumni have trouble finding their way around campus as it continues to expand and update its buildings. NMU freshman enrolling now have the choice of over 150 bachelor’s or associate’s programs since NMU has taken on the role of community college

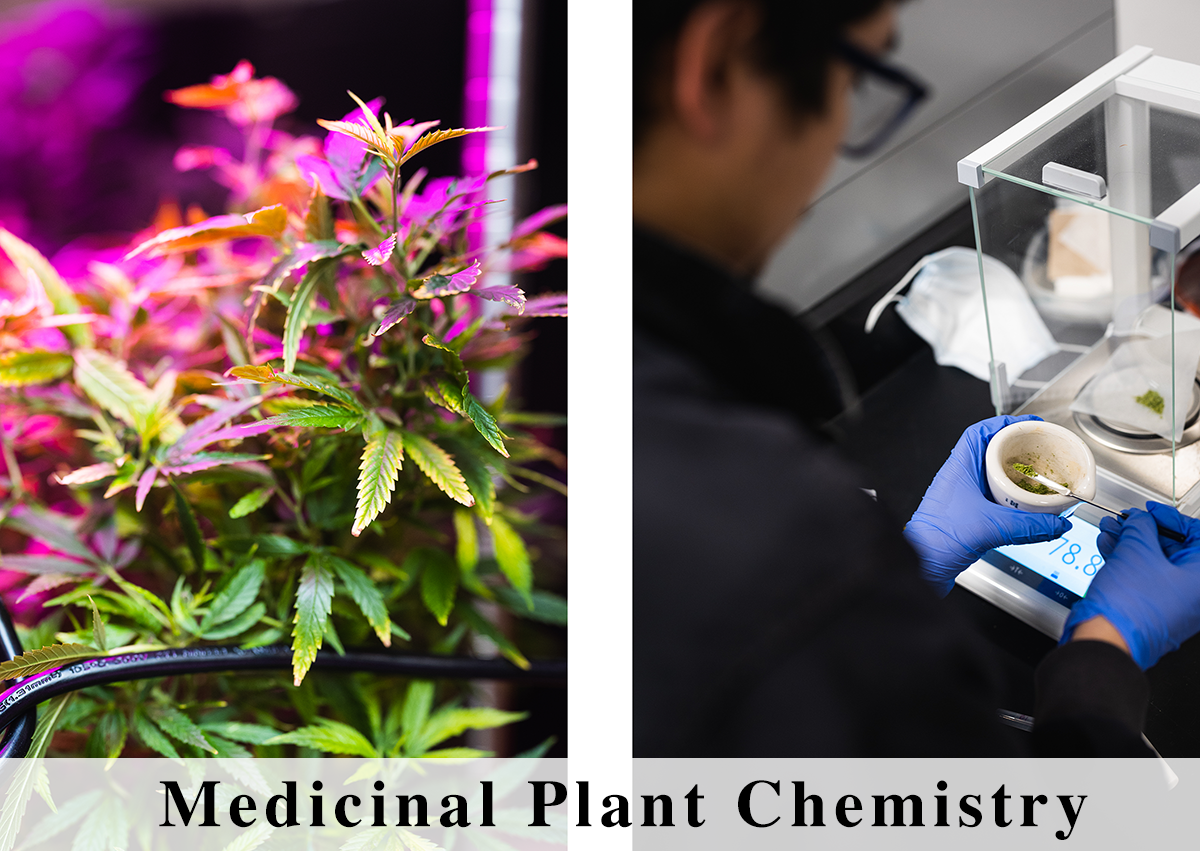

Northern has changed dramatically—both intellectually and physically—from its humble beginnings as a teacher training outpost for U.P. teachers. Today, even fairly recent alumni have trouble finding their way around campus as it continues to expand and update its buildings. NMU freshman enrolling now have the choice of over 150 bachelor’s or associate’s programs since NMU has taken on the role of community college  for Marquette and Alger counties. Students can take courses in fields that couldn’t have been imagined when Northern Normal’s first graduating class earned their teaching certifications, like cybersecurity or medicinal plant chemistry. However, despite all that has changed, the core of Northern remains. Perhaps this balance between remembering the past and embracing the future is best exemplified by the literal Heart of Northern: in the early 20th century, it appeared as a raised mound in the center of

for Marquette and Alger counties. Students can take courses in fields that couldn’t have been imagined when Northern Normal’s first graduating class earned their teaching certifications, like cybersecurity or medicinal plant chemistry. However, despite all that has changed, the core of Northern remains. Perhaps this balance between remembering the past and embracing the future is best exemplified by the literal Heart of Northern: in the early 20th century, it appeared as a raised mound in the center of  campus and served as a spot for social and fraternal ceremonies, pinning ceremonies, and probably a few proposals. Much of it was demolished in 1963 to accommodate a parking lot, but it was revived and reshaped to the east of the former Jamrich Hall in the late 1990s. Now a raised garden bed in the shape of a heart in front of the new Jamrich Hall, it stands as a testament that no matter the changes Northern has experienced since its humble beginnings over 120 years ago, its heart will endure.

campus and served as a spot for social and fraternal ceremonies, pinning ceremonies, and probably a few proposals. Much of it was demolished in 1963 to accommodate a parking lot, but it was revived and reshaped to the east of the former Jamrich Hall in the late 1990s. Now a raised garden bed in the shape of a heart in front of the new Jamrich Hall, it stands as a testament that no matter the changes Northern has experienced since its humble beginnings over 120 years ago, its heart will endure.

Kerri Schuiling

9th President of Northern Michigan University