Written by Will Sharp, Graduate Assistant, Beaumier U.P. Heritage Center.

Stories and language help show us who we are, bridge experiences and have capacity to instill a sense of belonging. Narratives that tell of our origins, creation, and why the world is the way it is are common in almost all cultures. Why certain stories are remembered and why some are repressed begs considerations of colonization, migration and human history.

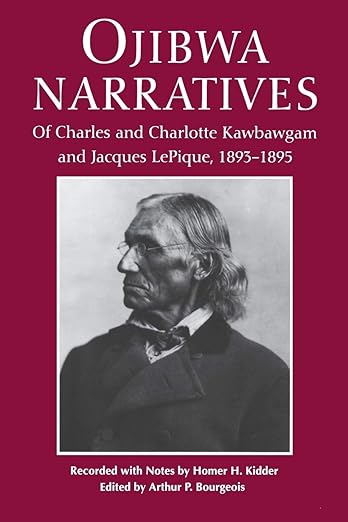

As Arthur P. Bourgeois, editor of Ojibwa Narratives of Charles and Charlotte Kawbawgam and Jacques LePique notes, “we live immersed in stories, the narratives that we tell or hear told, stories that we imagine… Narratives can be viewed as a way of knowing and remembering, and as a means of shaping or patterning emotions and experiences into something whole and meaningful” (Bourgeois, 1994). These words hint towards story as both archive and act — a means of situating ourselves at the intersection of stories not yet completed.

This idea of storytelling takes ceremonial form in Ceremony by Leslie Marmon Silko of Laguna Pueblo descent. Storytelling becomes medicine: an act of renewal that bridges the ancestral and the immediate, the mythical and the lived. The written word traces and tends what has been said, giving shape to memory’s echo. Oral history and retelling are not passive inheritances but dynamic practices of survival and flourishing—ways communities gather grief and praise into coherence, carrying memory forward not as record but as ritual. Through this lens, narrative becomes both remembrance and restoration: a living pedagogy that remembers the world (Silko, 1977).

One faculty member at Northern Michigan University (NMU) who has done this work of remembering and restoration is Shirley Brozzo. Shirley is an Elder in the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community and creator of the class ‘Storytelling by Native American Women’ at NMU. When asked what the main inspiration for the course was, she remarked “my own love of telling stories”. This course examines a myriad of historic and contemporary aspects of Native life through the eyes and stories of Native American women. Subjects include customs, culture, family, generations, mothers, daughters, grandmothers, art, education, fiction, poetry, political activism and spirituality.

Shirley began her NMU career with the Multicultural Education and Resource Center as a student worker during her undergraduate studies. She recalls taking the only Native course that was offered at the time. This class was ‘Native American Literature’, and was offered through the English Department. As Shirley continued on with her studies, she was one of the students interested in beginning the Native American Studies Minor. Shirley majored in Accounting, knowing that this field offered job stability, but looked into a Master’s in English because she “had to get my stories out.” She notes that in her culture “We talk more so in circles. We come back to stories. We use language like: ‘Here's how this came about.” During her Master’s in English, Shirley worked as a Teaching Assistant in the English department, helping others to get their stories out. She was inspired by the academic confluence of literature and storytelling.

The Native American Women’s Storytelling class was one of the first classes along with the ‘Native American Experience’ class. Shirley notes that the Native American Experience course was open and encouraged for nurses, social workers and other students at Northern who may work with and engage Indigenous peoples. This class began as a University Studies offering. The coursework in both classes at times has held stories like those of women’s survival from Indian Boarding Schools. These stories are needed in order for us to show the trauma, the intergenerational trauma, the losses and the legacy of these injustices that continue today.

Professor Brozzo noted that when Richard Henry Pratt described his philosophy of assimilation, one idea stuck out to her, this being that ‘if you can get the women, you can get the tribe.’ This reminds her just how important the women are within the culture. Women play a large role in holding the fabric of the culture together with their educating, storytelling and developing language. These are the kinds of messages that are shown in the course. In this remembering is a kind of hope that things can be different, and that things have been different. Stories also tell of morals. They remind us to not take ourselves so seriously. They talk about the lessons from non-human relatives. They hold lessons for all generations.

Shirley said that NMU allowed her space and time to go to Native conferences and English conferences, where she had the chance to share her own writing and gather stories from other writers. In order to honor her culture, the storytelling course was offered mainly in the winter semester because “Most of our stories are only told in the winter. The winter is the time for storytelling”. In Ojibwa Narratives of Charles and Charlotte Kawbawgam, it is said: ‘During long winter months, folktales handed down for many generations were told by elders around the fire not only to entertain but to affirm belonging and to teach ethical precepts. Their narration was a dignified matter usually accompanied by a gift and preceded by a feast. Yet considerable scope was given to the story-teller's imagination, allowing dramatized narration and incorporation of new material. The role of the masterful story-teller was itself legendary as one who knew hundreds of marvelous stories that could make people laugh and cry’ ( Kawbawgam, p. 13).

Shirley later completed the then new Master of Fine Arts at Northern. Continuing her education towards the MFA meant she would hold the terminal degree in her field, a wonderful accomplishment. Authors Shirley included in her course ranged from Louise Erdrich, Wilma Mankiller, Joy Hargo and Beth Brant, along with many others. She exclaimed: ‘these women, all women have something to say.’

A key component of the course is that students have the opportunity to tell a story. For the final assignment, they are told to begin with any scene from any book or video used from their semester, then encouraged to add their own spin or twist to the story, perhaps adding details from their personal life or making up an alternate ending from the one presented. Oral tradition holds some contrasts from a more academic, Western idea of authorship and literature. The telling, and the re-telling, the orating– it gives the teller a choice of how to tell it. It allows for improv and intuition. The storyteller can assess: Who is in the crowd? What story do they need to hear? Do they need to be challenged today? Nourished? Surprised? What are they ready to hear? Shirley also noted that this form of storytelling also allows for embodiment and improv on the part of the teller. They can ask themselves before telling a story: What am I dealing with today? They can consider that maybe I am feeling my friend’s grief, sorrow, loss, and they can change the telling that day to move the weight of that sorrow. Maybe they are feeling excitement and courage, pushed forward somehow by the sunshine on a winter day, or a letter from a friend, and their telling contains that joy. The language, the story, if considered in this way, is about relationality, about the relationship of humans gathered together in order to be touched by something. She notes: ‘By telling these stories, everything, everything becomes enriched’. Below is a poem written by Shirley Brozzo.

The Voice of the Elders

This time the Elders shall have their voice

And their voices will resound loud and clear

Words of Dine, not Navajo

Words in Lakota, not Sioux

Words from Annishinaabe, not Chippewa

And the children of the seventh generation

Will hear and understand

The words of the Elders they hear

This time the Elders shall have their respect

And their wisdom will resound loud and clear

Honor the Elders

Honor the land

Honor thyself

And the children of the seventh generation

Will hear and obey

The strong wisdom of the Elders they hear

This time the Elders shall have their say

And their words will not fall on deaf ears

Spoken at home, not from nursing homes

Spoken slowly, not in haste

Spoken from the heart, not in jest

While the children of the seventh generation

Listen with heart and soul

To the wisdom words of the Elders

Yes, this time the Elders shall have their voice

And their voices will resound loud and clear

Tribal words

Honored words

Sacred words for all to hear

And the children of the seventh generation

Will recover their roots

For the day of the Elders is here!

– Shirley Brozzo

The history of exploring language, literature, and storytelling is rich indeed here on the lands of the Three Fire Confederacy and within the Northern Michigan University community. Large pillars in this are the legacy of the English Department, the Center for Native Studies, as well as the theater and language departments.

Russell Magnaghi in A Sense of Time wrote that the English Department’s role is to educate students in composition and liberal studies, and to provide advanced instruction for undergraduate and graduate students in English areas of study. Northern’s first English teacher was Flora Hill, who taught until 1905. The Department of Language and Literature was created in 1920 and James C. Bowman was appointed its chair. Under Bowman, the study of English at Northern expanded from its original focus on teacher training. Bowman served as director of debate, drama, forensics and student publications. Bowman resigned in 1939 and Dr. Russell Thomas became the department head. Mildred Magers became the first female professor at Northern to receive a Ph.D. (University of Michigan) in 1944, who was also in the Department of English.

Northern’s graduate studies program began in the mid-1970s and offered a master’s degree in literature. In 2000, the English Department began offering NMU’s first terminal degree, a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing. The current MFA has four tracks: fiction, creative non-fiction, poetry, and hybrid.

The English Department has produced several publications featuring student or faculty writing: The Quill, 1914-18; Comment, 1961; Driftwood, 1964; Horizons, 1964; The Intruder, 1972; Mandala, 1971, 1972; The Golden Fern, 1981; The New Yooper, 1983; 1984; Limited Space, 1984; Engrams, 1985; Revisions, 195; AG-Student Writers and Artists, 1989, 1990; The Dark Tower, 1990-96; Thaw, 1996-99; and Hartley’s Review (not dated). Since 1996, the English Department has been the home of Passages North, an annual literary magazine of national reputation that has been in publication since 1979. The North Wind is Northern’s independent student newspaper which was founded in 1972. The paper is published weekly on Wednesdays.

The Master of Fine Arts (MFA) is a three-year degree in Creative Writing. Genres include fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and occasionally screenwriting and hybrid work. The degree is not restricted to one genre, so students are able to weave genres. Within the program, students complete a thesis manuscript which may be poetry collection, novel, essay collection, or hybrid work. Students are also encouraged to participate in a public MFA reading. The program description notes that the environment, the place — a natural landscape in the North Woods — becomes part of the creative writing lifestyle. More information about Creative Writing at NMU can be found here, by reading Bella Markham’s article ‘A Way With Words’.

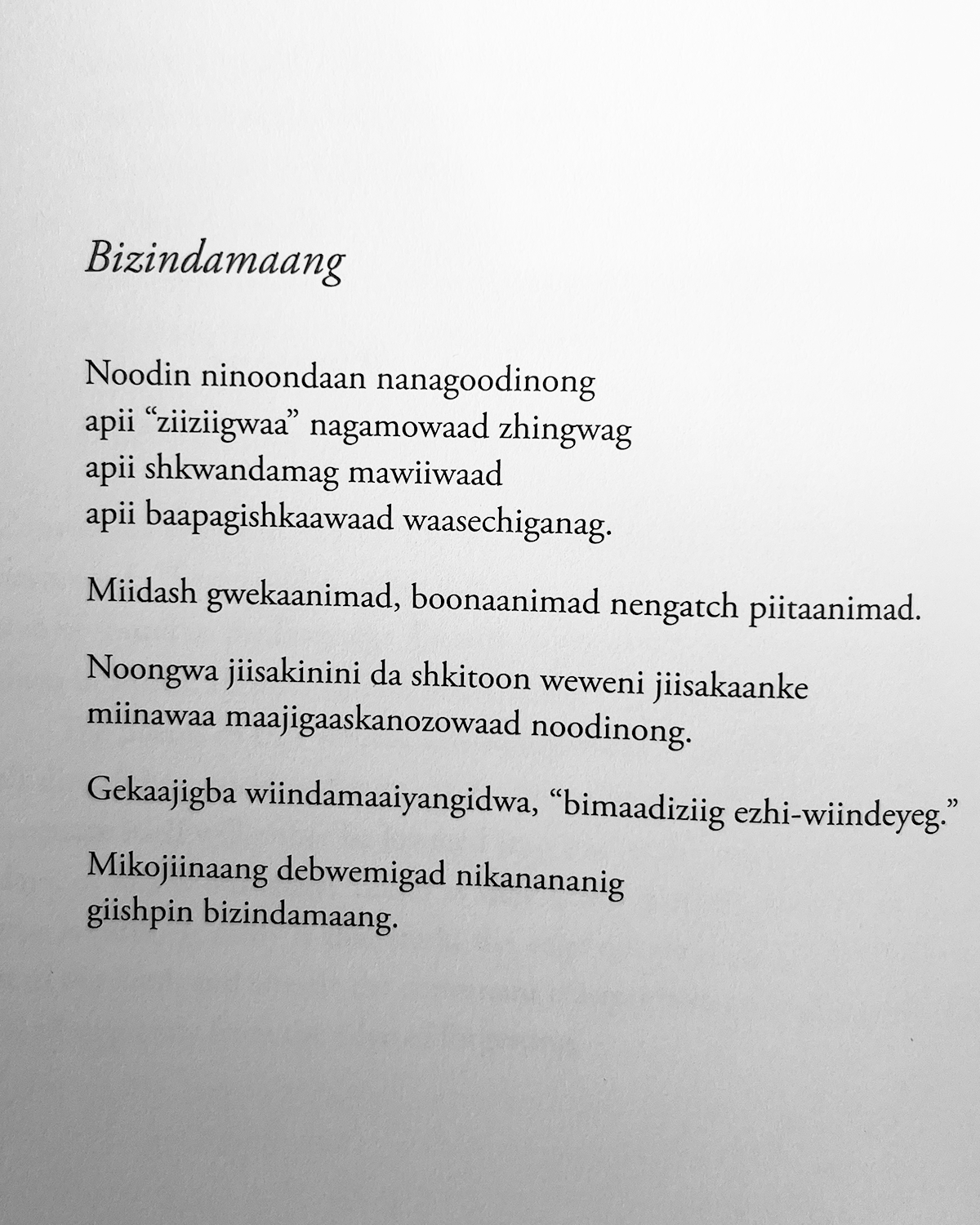

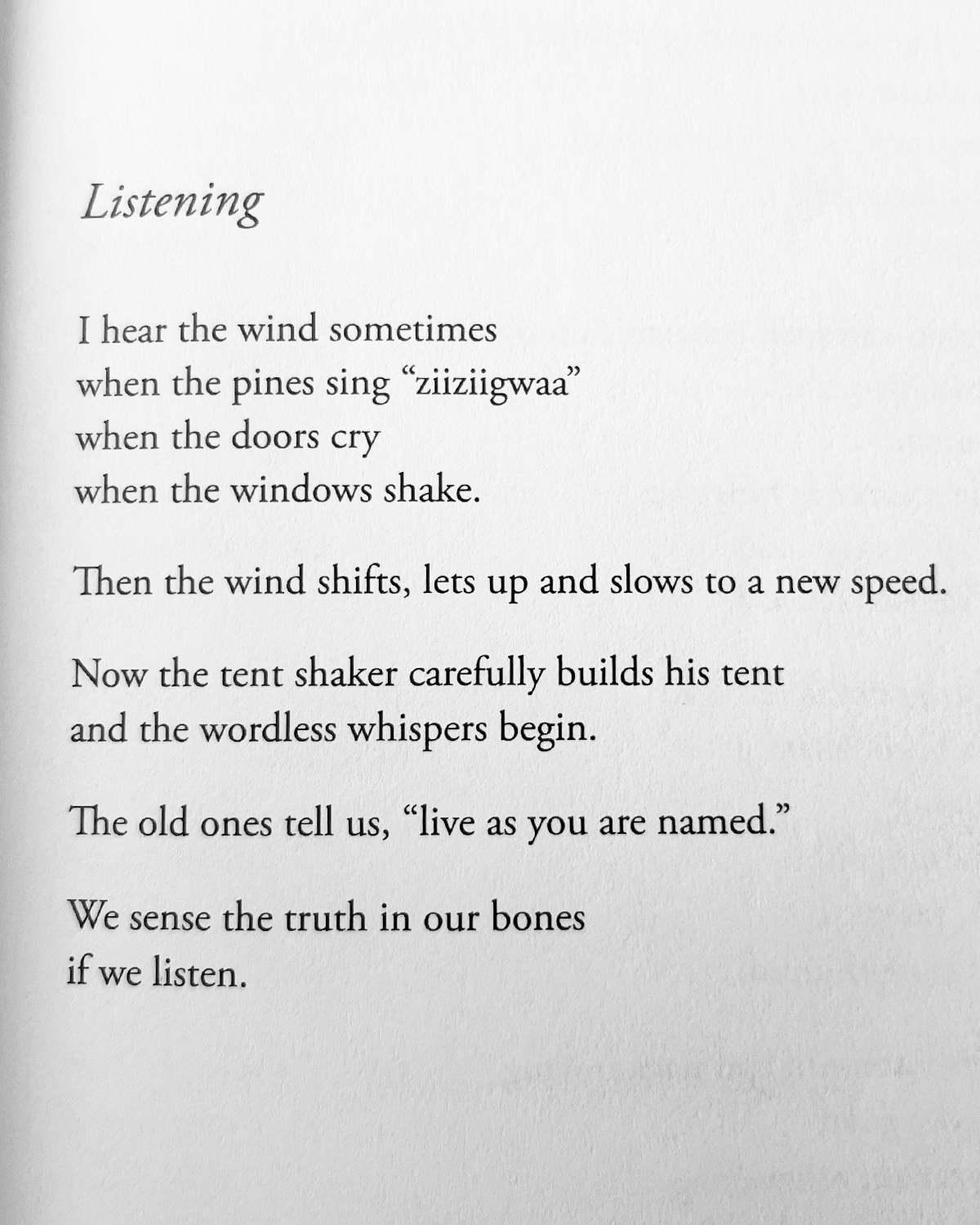

The language in which a story is written and told has a strong impact. The impact of settler colonization in America has included a widespread project to Anglicize language. The languages which have been spoken here for generations and generations have been lost and remembered again throughout the generations. Perhaps stories, poems and literature could be shared in more than one language. Perhaps this could help us arrive at a more authentic or nuanced place, where culturally we are open to how something may be told in a different way. A book of poetry by Margaret Noodin Weweni: Poems in Anishinaabemowin and English shows an example of how this could be done. This book was published with support from the Made in Michigan Writers Series. The Anishinaabemowin word "weweni" means something similar to gentleness, ease or sincerity. Noodin’s poems were first written in the modern Anishinaabemowin double-vowel orthography and then translated on facing pages in English. The poems speak to the interconnectedness of relationships and moments of grief and reverence. Translations from Anishinaabemowin to English offer challenges of meaning. Sometimes English approximations bend language in new directions, while other times ideas or concepts are unable to move from one language to another. It is important to note the word approximations. That is what a translation from one language to another is, an approximation.

Bizindamaang by Margaret Noodin

Another large character in the history of place-based storytelling in Marquette is Jonathan Johnson. Like Brozzo, Johnson is an alumnus of the NMU MFA program, and a pillar of language, poetry and writing in the area. His poetry has been published widely in magazines, anthologized in Best American Poetry, and read on NPR’s Writer’s Almanac. He migrates between his Lake Superior coastal hometown of Marquette, Michigan; his ancestral glen in the coastal Scottish Highlands; and Eastern Washington University, where he is a professor in the MFA program. He writes about place as muse, as beloved. His writing comes from longing. He talks about moving around a lot as a child and always longing to be back on his family’s farm. His migratory lifestyle between Michigan, Washington, and Scotland has him longing and thinking about place often. In his new book, The Little Lights of Town, Johnson reflects on his deep roots in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and the landscapes, communities, and quiet resilience that inform his work. He shares how he moved from poetry into fiction, what drives his sense of place, and why he is drawn to the tension between isolation and connection in the North Woods. Johnson held a reading event for his new book published by Carnegie Mellon University Press, at Peter White Public Library on November 13, 2025 in collaboration with Peter White Public Library, Marquette Poets Circle, and the NMU Department of English.

On a recent interview on WNMU, he describes his home here as a stool with three legs: 1) the wildness and otherness of the inland sea (Lake Superior) 2) the trees and forest as companion and 3) the community, the village, including ‘the lights of town.’ He eloquently talks about the moment driving back into Marquette, rising atop the hill in Skandia, and seeing the town nestled in the Huron mountains, the lake, the forest and far off in the distance– the lights. He and the interviewer, Hans Ahlstrom, talk about human connection to the oreboats coming in and out of harbor, viewing them with binoculars and tracking their routes through the Great Lakes on mobile apps. They talk about the lake as guide and anchor.

Ron Johnson, Jonathan’s father, was a Professor of English at Northern and also part of the legacy of creative writing in Marquette. Notes from his obituary remark that the Johnson family moved to Marquette in 1984 so that Ron could join the faculty of Northern Michigan University. Marquette became the family's beloved hometown, and Ron and his wife, Shelia, walked at Presque Isle Park daily when the ground was clear of snow. Ron helped found the nationally-respected graduate writing program, directed many dozens of fiction and nonfiction theses, and helped student writers find their words-and themselves. He retired in 2014 and is well-remembered around Marquette as a teacher of empathy, humor, insight, and kind encouragement.

Furthering on the exploration of place and literature, A Northern Today article from 2019 titled ‘Island Experience Inspires Writers’ talks about English graduate students and faculty members from Northern Michigan University traveling to Granite Island on Lake Superior. It states ‘NMU is the only public university in the nation to offer a course held in a lighthouse.’ The experience included group discussions, community building, and writing time. The experience is officially called a ‘Student Writing Residency.’ At the time, Professors Jon Billman and Amy Hamilton taught ecocriticism and environmental writing courses. In 2019, they accompanied three writing students to the Granite Island for the residency. Professor Billman said to the Northern Today News Director, Krisi Evans: “Isolation and humility are important for a writer's growth,” “Writers learn about themselves when they are forced to submit to the rhythms of such a colossal and powerful entity as Lake Superior. This course is the opportunity to go from classroom theory to outdoor practice in one of the most incredible ecoscapes on the planet. Northern offers the most dynamic opportunity of any writing program in the country. To be able to watch a sunrise or a storm come in from the tower of a historic light station is a special opportunity.”

The course and experience is still offered today. Students and faculty write field observations in journals, including sketches and watercolor paintings. They review books, maps and historic lighthouse keepers' logs. Historically, discussions incorporate course readings, such as Tristan Gooley's How to Read Water and Louise Erdrich's Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country. Students are also given time to work on their capstone writing projects related to place.

The three students with their journals on Granite Island

Owner of Granite Island Scott Holman shows an object to the group of students from NMU

Granite Island is a former U.S. Coast Guard Light Station that is perched on a rocky mass protruding from the water about 12 miles north of Marquette. NMU alumnus and former trustee Scott Holman owns the property, but is committed to making it accessible to his alma mater for research and educational activities. Granite Island also serves as an offshore solar radiation-monitoring site for NASA's Clouds and the Earth's Radiant Energy System (CERES) experiment. English and science converged when another MFA student, Olivia Kingery, ventured out to the island one afternoon to assist a NASA crew with its climate station, and to winterize the island.

Olivia Kingery is a farmer, poet and mystic living on her land in Chatham, Michigan with her animals and plants. She is a graduate of the MFA Program at Northern, attendee of the Granite Island Residency, and a deep lover of the waters and land here. During her time on the pilot program, the course was titled EN 595, Island Experience. She tells wonderful tales of her time on the island, where she created a project called ‘our mother is angry,’ which shifts between poem, fiction, and nonfiction, and can be read as one single poem. The notes, journal entries, and paintings in her journal were all a version of story mapping for her final work. One part of the project contains ‘postcards’ titled with each month. Another part is a companion essay. Each part engages the other, circling to make up the whole. To close her essay, she writes, “I am thankful for the island class, and the opportunity to push myself not only within my writing abilities but my all around artist abilities. I am thankful for the fellow writers and thinkers in this course, asking necessary questions and searching for answers. And, of course, I am thankful for two professors who brought this class to life, allowing us to engulf ourselves in the lake – for I always, and forever, want to be engulfed in Lake Superior”. Below is a poem from Olivia’s final project:

A postcard 37 nautical miles from the

edge of my heart

Addressed:

I need you to take three deep mouthfuls of azure blue,

flax flower blue, Prussian Blue, and become something

sturgeon of white bone.

This is a burning praise to Lake Superior

(I need you to become a burning praise to Lake Superior)

Photo on front of card:

White and red blanket, maybe checkered, sand already on

the peanut butter and jelly. The sun, which you think takes up

the whole sky, burns scented circles through the air. Your mother

is laughing, and by mother I mean lake, bending back

neck to show full breadth of teeth, maybe white capped swallowing

clear, water almost pansy purple, imperial purple, a plum purple

you can taste on the bottom of your tongue.

Back of card written:

When I was 8, I heard a voice tell me I would come to know

the waters of my mother. I baptized myself in her, became

Berlin Blue in her.

Signed:

This could be you, or anyone desperately gasping for one more

Inhale, either of water or air, the scented circles, the sturgeon white

bone, the burning praise.

The place here has had a profound effect on writers, poets, authors, and oral storytellers for generations, and certainly will for generations to come. Each of them have found new ways to honor place and call home beloved. Many of them also explore how these stories are told, where that is through poetry, oration, or different forms of reanimation. The significance of language and creating language of place has long been a priority and value of peoples living here, long before Northern was formed. Northern has done its work cross departmentally to support this work. The creation of containers and experiences for the exploration of place through oration and written word has happened in a myriad of ways. The English Department has created unique writing residencies, the Center for Native American Studies has offered the course titled ‘Storytelling by Native American Women’, and the MFA program in Creative Writing has allowed writing hopefuls a chance and seasoned writers a place to expand their careers and pass along their wisdom. May this tradition and legacy continue on, enriching the lives of the students and the community. May the language and gathered stories be burning praise for the land and waters held dear by all who live here.

Sources:

Central Upper Peninsula and Northern Michigan University Archives

Brozzo, S. (2025, November 11). Discussing her course ‘Storytelling by Native American Women’.

Evans, K. (2019, October 24). Island experience inspires writers. Northern Michigan University. https://news.nmu.edu/island-experience-inspires-writers

Hilton, Miriam. Northern Michigan University – The First 75 years. NMU Press, Marquette, 1974.

Kingery, O. (2025, November 14, 2025). On Place, The Lake and Granite Island.

Johnson, R. (2024, September 12). Ronald Johnson – Obituary. Bonner County Daily Bee via Legacy.com. https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/bonnercountydailybee/name/ronald-johnson-obituary?id=56277835

Magnaghi, Russell. A Sense of Time: The Encyclopedia of Northern Michigan University. NMU Press, Marquette, 1999.

Noodin, M. (2015). Weweni: Poems in Anishinaabemowin and English. Wayne State University Press.

Silko, L. M. (1977). Ceremony. Viking Press.

Weeder, J., & Sharp, W. (2025). Pedagogy of the soul: Directed study in applied humanics [Unpublished manuscript]. Department of Social Work, Northern Michigan University.

WNMU-FM. (2025, November 12). Interview with poet Jonathan Johnson, “The Little Lights of Town: Stories” Peter White Library reading [Audio]. WNMU-FM. https://www.wnmufm.org/northern-arts-culture/2025-11-12/interview-with-poet-jonathan-johnson-the-little-lights-of-town-stories-peter-white-library-reading