Written by Will Sharp, Graduate Assistant, Beaumier U.P. Heritage Center

There are few better places to spend the summer than Marquette, Michigan, Gichi-namebini Ziibing. With the actual snow, and the memory of the snow finally thawed, wild berries soon cover sand dunes, rivers run with trout and the lake begins to warm. Marquette becomes a haven for travelers, adventurists, nature enthusiasts and students from the past up to present day. Arlene Gordanier is a graduate of Northern Michigan University from June 1967. Arlene graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in music education and a minor in sociology. Her certificate included an endorsement to teach any subject in the 7th or 8th grade. Arlene spent her career as an Upper Peninsula educator. Her love of Northern, the Upper Peninsula, and the natural beauty convinced her to ultimately decide to spend her life here. She remarked, “The pace of life and the love of creation is a way of life here.” Her NMU education and experience gave her many opportunities to lay the groundwork for her career and ultimately shaped her life.

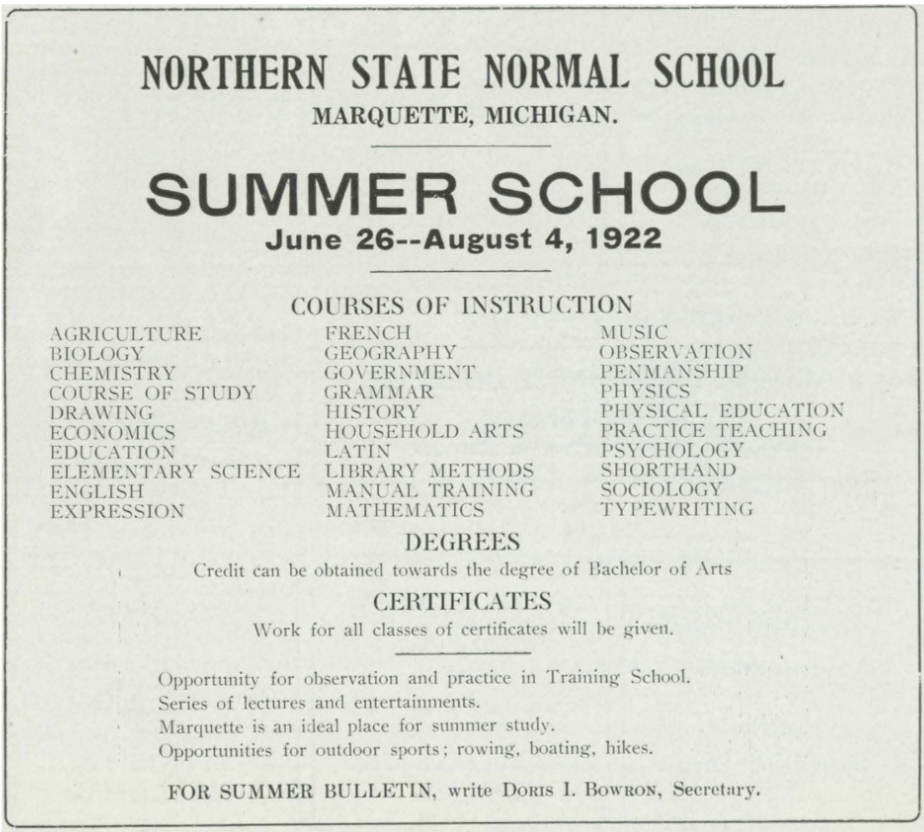

Northern Michigan University, since its founding as the Northern State Normal in 1899, has been in relationship with its summertimes, land and natural wonders. An article from 1920 in the Northern Normal News nods to Marquette as being the 'ideal place for summer school'. In addition, the author frames Marquette as the Queen City of the Upper Peninsula. The summer term was practical as it was romantic. In the beginning, the Northern State Normal only offered temporary or lifetime teacher certifications to its graduating students. The students were mostly women who taught in the rural, and sometimes, one-room schoolhouses of the region. Because they were busy teaching during the school year, they often came only in the summertime to receive instruction.

Beginning in 1900 a laboratory school opened, serving as a student-teaching site for students. The department was located in Longyear Hall of Pedagogy. From 1900-1907, it consisted of grades K-6. A decade later, a complete K-12 curriculum was established in 1917. It was first taught by five faculty, who were called critic teachers. In 1925, a new building was constructed for the laboratory and in 1927 it became known as the J.D. Pierce Training School, named after a former State Superintendent of public education. From 1925-1971, the Training School’s mission was to provide Northern’s students with an opportunity to observe teaching, study principles of education, and develop competency in methods. In 1971, the J.D. Pierce Training School formally shut its doors due many factors, including Michigan’s Educational Reform Act of 1969, which resulted in the shuttering of many alternative public schools.

Miriam Hilton’s book Northern Michigan University: The First 75 Years notes that students studying education found it easy to learn at Northern due to its accessible summer terms, where people would often combine a summer vacation with two to three lectures on pedagogy and education each week. The first summer session at Northern was held in 1900, which was primarily for teachers. Its cost was $3.00 for the entire six-week term, and housing in the dormitory was $3.75 a week. Since this first season, summer school has been offered every summer since, though it has taken on new shapes over time. During the course of the summer, visiting students were provided with social programs, tours and special speakers in the field of education. Often, the case was that teachers were upgrading certifications in between teaching calendar years, so the summer served as the perfect season for studies. Miriam Hilton tells tales of visiting professors who visited Northern to teach summer terms. She notes that full-time faculty and staff thought of them as interesting people and these visiting professors were happy to spend the summer in Marquette. One visiting professor's wife remarked, “When the phone rings, it's someone asking you to go on a picnic, not to serve on a committee” (personal conversation, Mrs. Albert Marckwardt, August 1951.)

John D. Pierce School wood shop, 1927

Northern News articles from the early years, when the school was called Northern State Normal, describe the summer climate as ideal for study. One author wrote that the air was pleasant and it was especially appreciated by those who lived farther south. The background and classroom for studies was written about as including rugged hills, covered forest, river gorges, and the clear blue of the great lake. In those days, Marquette was thought of as a charming city during summer. During summer terms, daily excursions were made for the study of geography and nature. Miriam Hilton writes that school hours were even arranged with recreation in mind. Parties and picnics were frequently organized, and the campus provided hobbies like tennis and basketball. For the summer of 1920, the summer school tuition fee was $5.00. Rooms were $1.50-2.00 per week. In addition, special courses were offered for those who expected to teach in rural schools. Certificates offered included the Life Certificate, the Three-Year Certificate, and the Rural School Certificate.

A Northern News article, titled Summer Session, 1919, states that The Normal School’s Training School was in ses sion during the mornings of the summer term. Special courses were offered in Music, Drawing, Nature Study, Agriculture, Manual Training, Commercial Work, Domestic Science, and Physical Training. All of these were designed to give teachers the best possible working knowledge of the subjects. The courses were practical rather than theoretical, so as to make them as useful as possible to teachers in their actual work.

sion during the mornings of the summer term. Special courses were offered in Music, Drawing, Nature Study, Agriculture, Manual Training, Commercial Work, Domestic Science, and Physical Training. All of these were designed to give teachers the best possible working knowledge of the subjects. The courses were practical rather than theoretical, so as to make them as useful as possible to teachers in their actual work.

A Northern News article from the following year, 1920, stated, “There has not been one day during the entire term when students could not do work in comfort. For study purposes, the climate is ideal. Students go back invigorated by the splendid air and climate of this region.” The author of the article argues that Marquette should be a Mecca for teachers from the middle states who desire a restful climate in connection with study.

A 1992 interview by Russell Magnaghi with Anita Meyland captures an early snapshot of Northern and the summer term: “I have seen the college go from a teacher's training center, to a Normal, to a College, to a University. There were four steps. When we came, it still was kind of a teacher's training center. They had the women from the surrounding area, most of them would come in the summer time and take their summer vacation.”

As Northern grew and more offerings beyond education were added, the College, and eventually the University, adjusted summer terms and programming to meet the desires of its students. In preparation for summer 1996, the ‘Summer College’ was created to emphasize that this session was a critical component of the year-round curricular effort. The ‘Summer College Advisory Committee’ was established to provide leadership in the development of an integrated Summer College curriculum.

A 2005 North Wind article by Kristen Kohrt tells a story of her and her partner on "a rare sweltering Marquette summer night." To escape the heat of their apartment, they got in the car and drove down by the lake: "Before we kne w it, we had the seats back and were falling asleep to the sound of the waves and the cool lake winds. We awoke to the sight of the sun rising over the sparkling lake, it was so bright, we had to avert our eyes, yet it was so beautiful. For a moment, I felt as though we were parked near the ocean on a tropical island, forgetting that just months ago giant ice chunks were floating in the water and snow was blanketing the beach." The North Wind columnist finishes her article saying, “If you haven’t spent at least one summer in Marquette during your time at Northern, you are cheating yourself out of one of the best parts of a college experience at NMU.”

w it, we had the seats back and were falling asleep to the sound of the waves and the cool lake winds. We awoke to the sight of the sun rising over the sparkling lake, it was so bright, we had to avert our eyes, yet it was so beautiful. For a moment, I felt as though we were parked near the ocean on a tropical island, forgetting that just months ago giant ice chunks were floating in the water and snow was blanketing the beach." The North Wind columnist finishes her article saying, “If you haven’t spent at least one summer in Marquette during your time at Northern, you are cheating yourself out of one of the best parts of a college experience at NMU.”

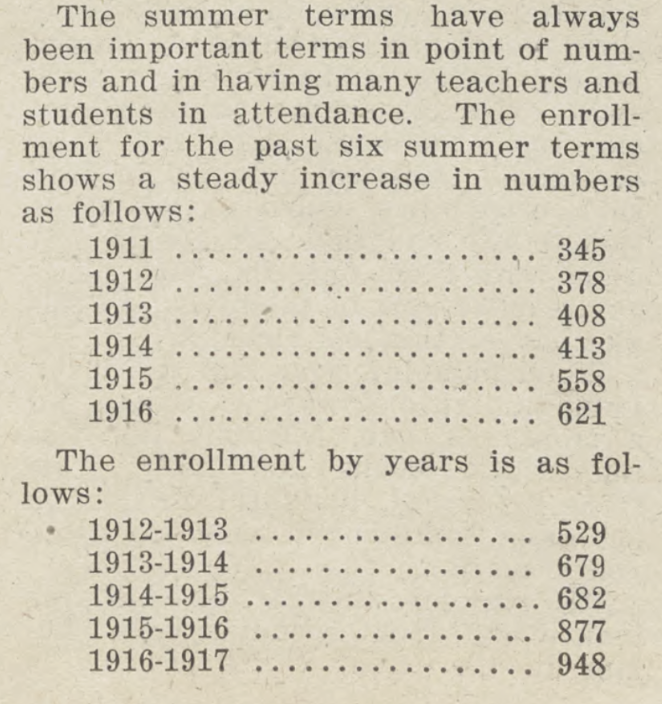

Summer enrollment has changed over the course of Northern’s history. A Northern News article listed the enrollment for the summers as compared to the entire year from 1911 to 1917. The data revealed that for these years, approximately 50-60% of students were attending summer terms.

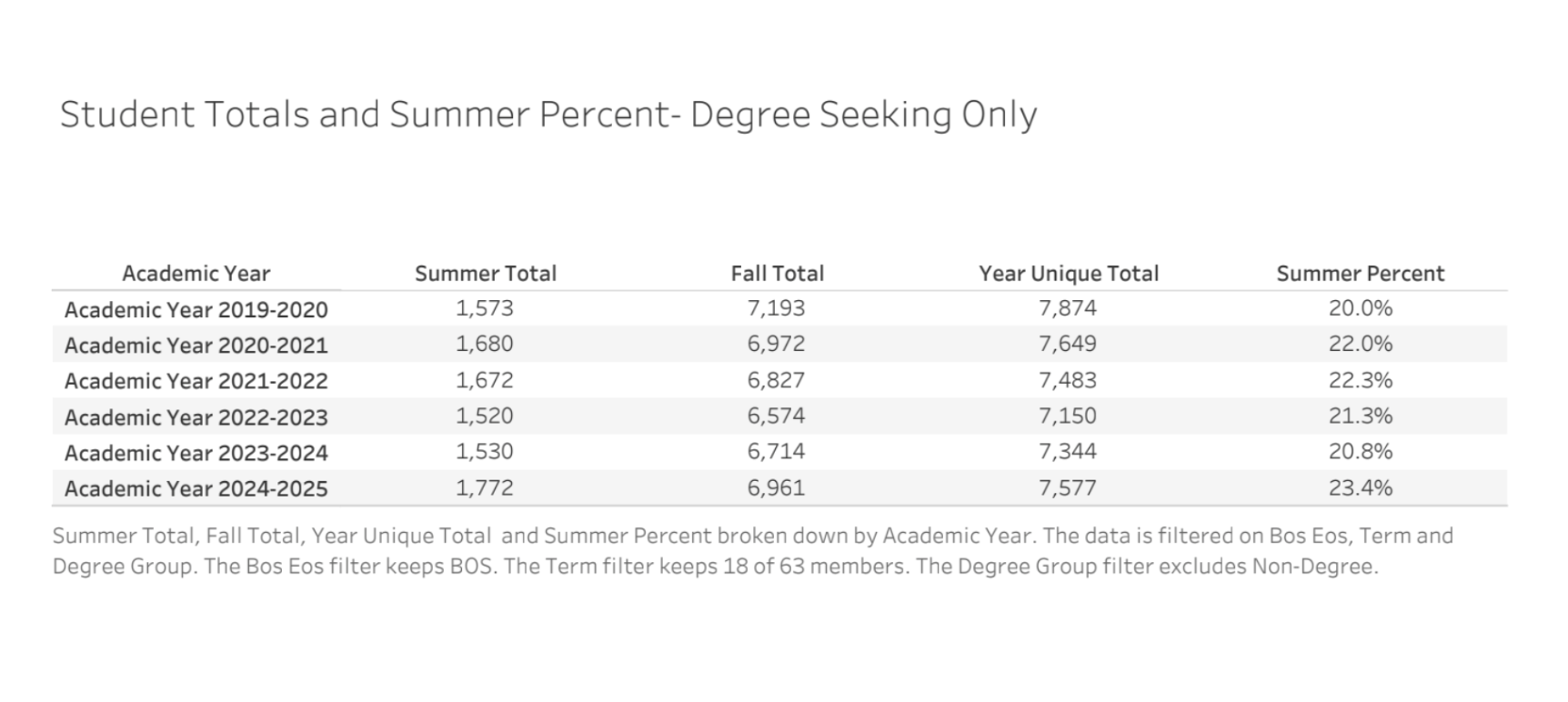

The Office of Institutional Effectiveness ran similar numbers for 2019-2025. Ryan Poupore, an Institutional Researcher, offered the following data:

Internships, study abroad, and directed studies were removed from the data. The data was collected for degree- seeking students only. The percentage of students who were attending summer terms for these years seems to be around 20-23% of the total enrollment for the entire academic year. This is quite a decrease from early years at Northern, where percentages were up near 50%!

Since Northern has moved onward from being a teacher’s only college, summer terms have transformed, and continued to add offerings and programs to meet the needs of the students and the region. Key focuses of summer at Northern from 1960 onward include special institutes, camps, assemblies, concerts, continuing education and workshops. Miriam Hilton shares that as time went on, Northern's summer concerts became central to summer activities. In 1968, offerings included summer music camp for junior and senior high school students, a coaching school, a high school debate workshop and two national science foundation sponsored programs. An article from the Northern News, 1968, says students attending summer sessions can partake in Campus Entertainment such as American Folksingers, Summer Band and Chorus, and Film Screenings.

In 1975, Summer session workshops included organizational development, educational planning, and the future evaluation of performance. Subject workshops were held in the areas of industry and technology, conservation, business, education, speech pathology, English, debate, home economics and physical education and recreation. An unusually large selection of summer camps for high school students was held, including boys’ baseball, girls’ gymnastics, boys’ football, swimming, cheerleading, wrestling, basketball, debate workshops, forensic workshops, visual arts prep school, and music (The Campus Review, 1975.)

In the spring of 1983, the ‘Summer Institute’ began. Northern was selected as a site for the state board of education’s ‘Summer Institute’ for 125 gifted children in 10th and 11th grades in mathematics and art and design. This was supported by a state grant to five colleges. The institute was conducted for several years before Michigan Tech was awarded the grant. In later years, the Institute operated under the name Seaborg Center.

![Northern Michigan University. Office of the Photographer. John Kiltinen and Group of Seaborg Summer Science Academy Students (Part of the NMU Historic Photographs Collection) [Photographs]. https://uplink.nmu.edu/node/48564](/maamawi-ozhigi/sites/maamawi-ozhigi/files/styles/re_full_width_sm/public/2025-10/seaborg-summer-institute.png.webp?itok=632CrDcH)

John Kiltinen and a Group of Seaborg Summer Science Academy Students

The Center for Native American Studies (CNAS) has played a large role in summer coursework and summer programming. CNAS has been a seed planter for the long-term growth of students, always honoring their unique journey. Their summer initiatives have served as scaffolding to onboard students for the rest of the academic year, to connect students and the community to the wisdom of elders and to connect with the nourishment of the land on which they study, labor, and rest. In a 2013 summer article from the Anishinaabe News, a publication of CNAS, it talked about a summer course offering called ‘Kinomaage,’ "Earth shows us the way’, which is offered to this day. In the course, students get the chance to visit and tend to different places across the Upper Peninsula. The author of the article says the course takes students to listen to the land, learn about traditional uses of plants, and engage in hands-on learning. ‘Kinomaage’ is about disseminating the traditional ecological knowledge of Anishinaabeg elders in order to provide students with an eco-cultural understanding of place and the more-than-human community. This is just one example of the life-giving and life-supporting summer programs CNAS has begun. Their mission of strengthening student engagement, interaction and reciprocity with Indigenous communities can be seen in all they do.

Blueberries by Native American Studies at NMU. Picked August 2010. Courtesy of Center For Native American Studies

Northern Michigan University’s website states that summer is a great time to visit, enjoy and explore the Greater Marquette Area. Offerings include sports camps, hands-on career exploration, for-credit courses and continuing education opportunities. They make it evident that NMU offers valuable programming for people of all ages throughout the summer.

Youth programs are a large part of summer campus activities. This includes Wildcat Youth Camp: a place for children from kindergarten through 5th grade, which focuses on teaching new skills, promoting teamwork, and encouraging sportsmanship. Sport camps are offered in basketball, cross country, track & field, football, hockey, lacrosse, soccer, swimming & diving and volleyball. Summer College for Kids includes a program for kids in grades K-8 to engage in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. The Future Educator Academy offers hands-on experience working with elementary students. The U.P. Future Health Leaders is dedicated to health education and health career exploration. The NMU Wildcat Performing Arts Academy offers comprehensive training, mentorship and exposure in various arts disciplines such as dance, acting, vocal training, and theater production. GenCyber Camp engages high school students interested in the fundamentals of cybersecurity. Environmental Science Camp invited high school students to hike geological landmarks, discover local natural resources, experience sustainable community development, and study sustainability issues.

Northern’s office of Continuing Education and Workforce Development is always offering summer opportunities for workforce, professional, and personal development. Opportunities include Real Estate Appraiser continuing education courses, Truck Driving School (CDL), Child Welfare Training, MSHA & HAZWOPER Training, Motorcycle Safety, Bus Driver Safety, GED Testing, self-paced online courses, and Pearson Vue Testing.

Within the Office of Opportunity, Empowerment, and People (OEP) lies staff members, Dr. Shawnrece Butler and Justin Schapp. Each of them play a large role in serving students during the summer term. They say their work has all to do with access, wrapping around the students, getting them resources they need to thrive, so that they will graduate and graduate well. Since the beginning of Northern’s founding as the Northern Normal, access to education and resources has been woven into the fabric. For example, the story of Charlotte and Bessie Preston is one to be remembered. They were Marquette youth, born to a Jamaican barber and business owner. Charlotte was the first black student at NMU, and Bessie went on to become the first graduate of color from Northern in 1903. These women were among the very first students to attend Northern, and more than likely to have attended summer school.

Dr. Butler is the Assistant Vice President of the Office of Opportunity, Empowerment, and People. She shared about The Wildcat Collective, which is a multi-year mentoring program offering paid summer internships, hands-on experience with local businesses and organizations, financial support for summer housing, transportation, and food assistance. The program’s aim is providing career-boosting connections and pathways to employment. Many graduates find work in Marquette and the Upper Peninsula! Another summer resource is the MiLEAP Summer Housing Support Program. This is a grant funded initiative providing tailored resources and support to help Pell eligible, first generation students transition, excel, and achieve their goals. Per Northern Michigan University, The First 75 Years, even in the early 1900s, student housing was hard to find, especially in the summer.

The BIPOC Outdoors Summit is a gathering that brings together outdoor enthusiasts, community builders, and those seeking restoration and inspiration. This program is open to all with the mission of moving toward a healing, joyful outdoor community. Conversations focus on belonging, leadership, and community. There are restorative spaces for reflection, connection, and self-care. The event is noted to have dialogue around ancestral practices, land relationships, the power of story in cultural and personal healing. There are interdisciplinary approaches to equity in environmental contexts. 2025 keynote presenters and panelists included folks such as James Edward Mills, author of ‘The Adventure Gap’: Changing the Face of the Outdoors, Kyle Mays (he/him), an Afro-Ingenous writer and scholar, and Alice Jasper (she/they) a sustainability professional and outdoor enthusiast. Both Dr. Butler and Justin Schapp had smiles on their faces as they reflected on the charmed experiences at the 2025 BIPOC Summit. A sudden community formed, time outside lowered blood pressure, and even inconveniences and hiccups to transportation and programs were seen as moments to stay in, enjoy, and embrace the sacred time of learning and communing. The Summit is intentionally intergenerational, and I was told there was ages 3-80 there. Dr. Butler said that engaging the youth in programs like this begins to form place-based connection and reciprocity with the land. Their hope that ‘the connection is never lost again’.

Justin Schapp is a Deer Clan citizen of the Seneca Nation’s Ohi:yo’ Territory, and the Assistant Director of KCP Grant Administration & Faculty/Staff Initiatives. He communicated about plans for food sovereignty initiatives for summer terms and beyond. Justin is collaborating with the Great Lakes Intertribal Fish and Wildlife Commission and others such as the Upper Peninsula Land Conservancy to continue the wonderful legacy of wild rice programming in the Upper Peninsula. These kinds of place-based initiatives and programs he believes can be a strong scaffolding to help link to class work during the rest of the school year. Justin is also in favor of more creative summer housing ideas, namely an incredibly creative summer sailboat housing idea with slips at the harbor for NMU students!

Dr. Butler said that part of what brought her here was noticing how over time this university has always responded to what the region and its people need. Summer programs like The Wildcat Collective, MiLeap, and the BIPOC Summit are a continuation of the school’s original mission. The Northern Normal  school was founded to fill a gap– to educate teachers so that their youth would have quality education. The soul of the school over time has grown– grown with access, community engagement, educating educators, connection and wonder of place, building reciprocal relationships, and inspiring future leaders. The summer term exists as a potential gap in the development of students, but for Northern, it has long been a time of opportunity. Northern is doing this today by providing resources to everyone, and eloquently and swiftly moving to where the need is.

school was founded to fill a gap– to educate teachers so that their youth would have quality education. The soul of the school over time has grown– grown with access, community engagement, educating educators, connection and wonder of place, building reciprocal relationships, and inspiring future leaders. The summer term exists as a potential gap in the development of students, but for Northern, it has long been a time of opportunity. Northern is doing this today by providing resources to everyone, and eloquently and swiftly moving to where the need is.

Sources:

Central Upper Peninsula and Northern Michigan University Archives

Hilton, Miriam. Northern Michigan University – The First 75 years. NMU Press, Marquette, 1974.

Magnaghi, Russell. A Sense of Time: The Encyclopedia of Northern Michigan University. NMU Press, Marquette, 1999.

Northern Michigan University, Center for Native American Studies. (n.d.). Anishinaabe News. https://nmu.edu/nativeamericanstudies/anishinaabe-news

Northern Michigan University. (2025). Home | Opportunity, Empowerment, and People. https://nmu.edu/empowerment/home

Northern Michigan University. (n.d.). Summer. https://nmu.edu/summer

UPLINK (Upper Peninsula Digital Network)