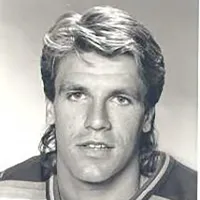

The genesis of Jim Hiller, New York Islanders Assistant Coach

By Michael Murray ’98 BS, ’10 MA

At age 33, Jim Hiller ’95 BS made the transition that every professional athlete eventually must make— from player to ex-player. While some athletes struggle with this change, coming to grips with a new identity and casting about for a new focus, Hiller knew exactly what he wanted to do next. In fact, he had been preparing for this moment for over half of his life.

As a teenager growing up in Cranbrook, British Columbia, Hiller was a self-described hockey nerd. Not only did he play the game at a high level, but he also studied the sport. He collected hockey cards, analyzed box scores and statistics, kept track of trades across the National Hockey League. By the time he was 16, he knew he wanted to keep playing as long as his talent gave him the opportunity—and then he would move behind the bench as a coach.

"I always had an eye on becoming a coach,” he said. “I thought that’s what I would do someday.” “Someday” arrived for Hiller in 2002, when he closed the book on a playing career that included 63 games in the NHL, a season with the Canadian National Team, and six years in Europe. That summer, when he was hired as an assistant coach for the Tri-City Americans of the Western Hockey League, he began the long climb up the coaching ladder with the goal of reaching the NHL.

Throughout his playing career, Hiller was a student of the game and a student of coaches. At every step of his journey—from juniors to collegiate hockey at Northern Michigan University to the pros—he tried to pick up whatever he could from the coaching staffs. “It was a real advantage knowing this is what I wanted to get into,” he said. “I was always watching, listening, talking to my teammates, getting a sense of how players think.”

Hiller arrived at NMU with his friend and linemate Scott Beattie in what became one of the golden eras of Wildcat hockey. In their sophomore year, 1990-91, NMU won the NCAA national championship. Hiller said everyone associated with the program had high expectations that year. “We all saw what a great job the staff did putting the team together,” he said. “We looked around and realized we had a lot of good players on that team.”

But good players are not enough. “We had a really talented team—just like everyone else. Three things really set us apart. First and foremost, we had camaraderie and character. We liked each other and had fun together... And then we had really good leadership from the coaches.”

Hiller’s three years playing for head coach Rick Comley ’73 MAE were instrumental in his own development as a coach-in-training. “Coach Comley was a big inspiration. I saw how the leader, the man at the top of the organization, could really have a big impact on the whole team. That opened my eyes. Those years made me appreciate the position and impact the leader can have.”

Most importantly, Hiller saw Comley had earned the respect of the players. The coach also “had a good sense of timing and a good sense of the moment. He knew when to be positive and encouraging, which might not have been that often. He knew when the time was right to inject his own personality.”

Hiller has fond memories of his time at Northern, on and off the ice. His wife, Kathy, is from Marquette, so they return often to visit family. “I had an incredible time at Northern,” he said. “It was capped off by the championship season, but I think about all the teammates I played with, the way the community supported us. I keep in touch with friends I made there all those years ago. It’s a special bond.”

When Hiller turned pro after his junior year, in which he earned second-team All-America honors, the biggest adjustment he had to make was playing without Beattie. They had been on the same line for five years, going back to juniors. “We complemented each other really well. Not having him as my centerman was the biggest adjustment. Looking back on it, I think I would have had a better career if he had been my centerman.”

From 1992 to 1994, Hiller appeared in 63 games with the Los Angeles Kings, Detroit Red Wings, and New York Rangers, scoring eight goals with 12 assists. Then, after two years in the minors, he jumped to Germany, where he was reunited with nine years as head coach of three different teams in two junior leagues.

In 2014, Hiller reached the NHL, joining the Red Wings as assistant coach under Stanley Cup winner Mike Babcock. The following year, he went with Babcock to Toronto, where he spent four years. He is now in his third season as assistant coach with the New York Islanders on the staff of another Cup winner, Barry Trotz. Throughout his NHL career, Hiller has often been responsible for coaching the power-play unit—and has received rave reviews from the players.

Beattie as linemates with the Rosenheim Star Bulls. Not only did Hiller regain his scoring touch, but he also built on his reputation for physical play. In 47 games that year, he led the league with an incredible 187 penalty minutes.

By his third year in Germany, Hiller had drastically cut his penalties and increased his scoring. His 67 points in 52 games ranked second in the league. Several of his teammates told The Athletic in 2019 that this change was the result of Hiller’s intelligence and ability to adjust. Derek Cormier said, “He realized that he didn’t have to play [a physical] type of game to get the time and space he wanted on the ice.”

That ability to interpret and take advantage of spacing has translated well to his coaching career. After two years as an assistant, he spent

“When he runs the power-play meetings, he’s very knowledgeable,” Toronto defenseman Morgan Rielly told The Athletic in 2018. Rielly’s teammate Patrick Marleau added, “He understands the game. So the way he talks to you, he sees what you’re seeing out there. And that makes it a lot easier to communicate.”

Hiller’s goal when he started coaching was to eventually become an NHL head coach. Until that opportunity comes, he keeps in mind one of the lessons he learned when he started coaching in the junior ranks.

“I realized it’s a hard game to play, and it’s a hard game to coach. It’s emotional, so I want to be balanced. I try to find the sweet spot of holding people accountable but also understanding that it’s a difficult game.”