1967

By Adelaide Banks ’74 BS

My father, William C. Sims, was stationed at K.I. Sawyer Air Force Base in the early 1960s. I graduated from Gwinn High School in 1967 and enrolled in NMU where my brother, William N. Sims, was a student.

With the military base just 20 miles from Marquette, there was a Black presence in the area. To a lesser extent, also in towns like Negaunee and Ishpeming where housing was secured until base housing was assigned. To my mind there was no open, evident racism. There were stares as some residents had never seen a Black person. They pointed us out to their children. But, I don’t recall hateful experiences.

By 1965, President Jamrich’s call south to Detroit and Chicago was heard and answered as students took advantage of the opportunity to attend NMU. They arrived to an open campus with integrated dormitories and people with last names they could not pronounce. Blacks soon owned their space on campus and called this home away from home. They respected the kindness of residents and merchants and felt well received.

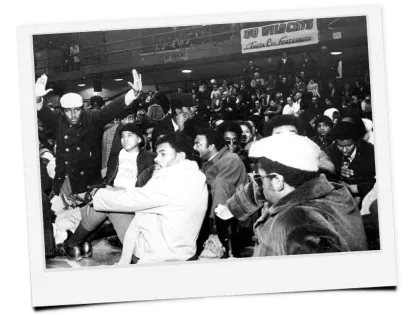

But these were racially charged days in America. The Civil Rights movement was not over. We were young and eager to express our ire with injustice. I don’t recall the reason that we occupied the basketball court before a game, but I doubt it had anything to do with local issues.

I was a student when Martin Luther King was killed. I speak for many Black students when I tell you that we were overwhelmed with pain and disbelief, not knowing how to express it, but tears seemed inadequate. The university arranged a memorial in front of the Admin building. I don’t remember much about it as we were all numb and it was a long time ago. But, we felt safe and protected in our grief at our school home. I know that soon after this we had a large event with Rev. Abernathy as guest speaker.

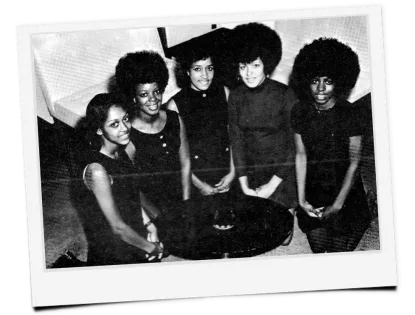

As was true across the country among Black youth, there was a strong Afro-centric presence while seeking identity and bonding with our African heritage. One of the fraternities had an event titled Zulu.

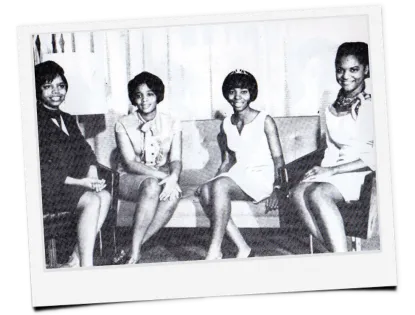

Student life was relatively tranquil with classes, good food served and all we wanted, playing cards in the student center and full access to campus facilities. Back then we had scheduled open house visits in dorm rooms with doors wide open. Doors were locked at night and parents had to provide written permission for girls to leave campus on weekends. But, we had fun and everybody knew each other.

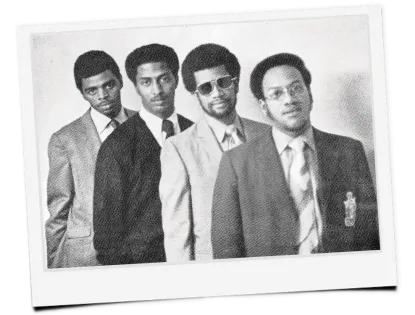

Almost from the start, Black men began organizing chapters of Alpha Phi Alpha, Kappa Alpha Psi and Omega Psi Phi. The women began later starting chapters of Alpha Kappa Alpha (I was president and founder) and I believe Delta Sigma Theta. I had left campus before Delta was started. These pictures and information are from souvenir booklets in my keeping and identify some of the active Black students between 1965 and 1972.

I met my husband at NMU, Reginald J. Banks, and we married after our sophomore year. Eventually we returned, lived in student housing with our two babies and graduated together in December 1974. My degree was in sociology. Immediately after graduating, we relocated to Atlanta, Georgia. He worked for Peat, Marwick, Mitchell CPA Firm and earned a CPA. Reginald died in 1999.

I found work at ADP, Automatic Data Processing, and later worked as a county social worker. I moved to Durham, North Carolina, earned a master’s in sociology and taught the subject between jobs as a mental health counselor and social worker. In 2000, I founded Read Seed, Inc., a nonprofit giving books to children to promote literacy and close academic gaps. After retiring, I began teaching Black American history and facilitating race relations workshops.

Another amazing note in my NMU connection is that all four of my immediate family attended and three of us received degrees. My mother, Martha Sims, received a master’s in education. She taught and retired from the elementary school at the base. After retirement, my father earned an undergraduate degree. My brother went to Vietnam and did not graduate. My two children are quite grown now and I am grandmother to four young adults.

I have two grandmothers first out of slavery who went to college and received degrees, and my ancestors have gone to college ever since. With my granddaughter just finishing her master’s degree, the graduation tradition in my family has been unbroken since after slavery. There are many black families who can claim that.

Visit asbhistory.com to find videos, podcasts, workshops and other resources on Black history and understanding race relations in America.

Read our conversation about current issues with Adelaide Banks.