Greetings NMU faculty and welcome to the ONLINE BYTE OF THE WEEK, a newsletter created to share current scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) related to the virtual learning space, online teaching best practices, EduCat learning management systems tips and techniques, and to spotlight the exceptional means by which we bring cyber learning to life for our students.

Vol. 1, Issue 45, June 15, 2020

Through June, the BYTE presents a four-part miniseries on the topic of blended or hybrid learning, one of many teaching design and delivery strategies that can be implemented to support our classroom capacity initiatives to maintain appropriate COVID-19 pandemic physical distancing policies during the Fall 2020 term and beyond. The HyFlex course design model, related to but not the same as the blended learning methodology, will be the subject of study in July.

This week, the BYTE provides a get started guide on how to design a hybrid course, filled with practical ideas, supported by well-respected research.

Hybrid Course Design Strategies

Learning Objectives

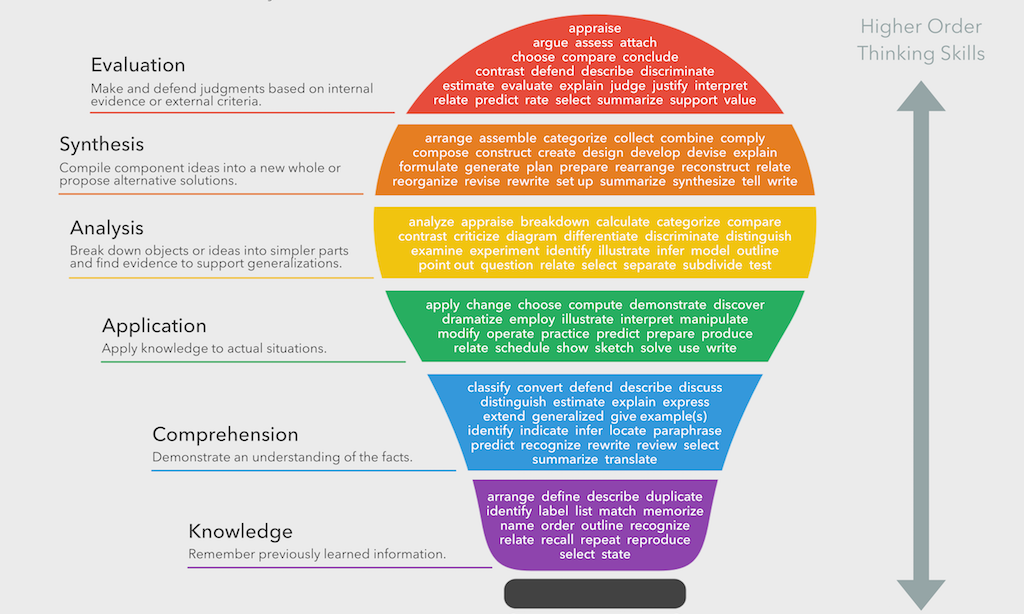

The first step of designing a hybrid course, or any course for that matter, is to lay out the learning objectives, what you want your students to know or be able to do at the conclusion of the course and for each segment of it, whether it be units, modules, weeks, or some other structure that best aligns with the course of study. Learning objectives should be clearly written and include action verbs (QM 2.1). Place the learning objectives in a prominent area of the course syllabus and in the EduCat course room.

Course Mapping

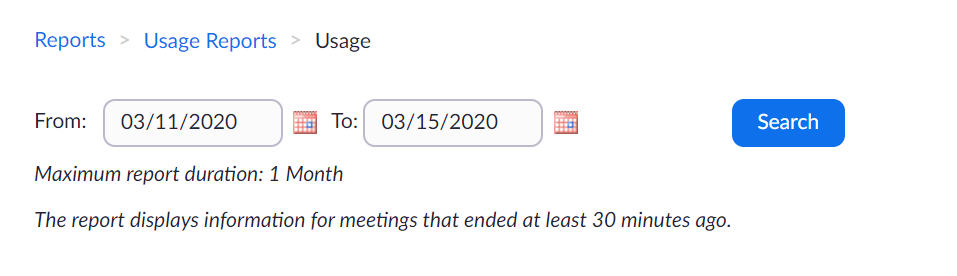

Next, create a course map or schedule, perhaps using a course re-design document if a course has already been taught, or a design document if not previously offered. Identify which day or days of each week will be face-to-face and online. Distinguish for your students if the online segment will be synchronous or asynchronous. If synchronous, provide students with virtual class participation instructions including the class meeting times and mode of attendance, such as Zoom. Publish an abbreviated course map in the syllabus and an unabridged version in EduCat.

Learning Activity and Assessment Selection

When selecting learning activities and assessments for your hybrid courses, consider which are most suitable for face-to-face or online delivery. Many activities can be facilitated quite successfully in the online learning environment with support from the appropriate technologies. Think about how the multimodal activities and assessments align with one another to achieve learning outcomes based on the learning objectives. In-class learning activities can ready students for the online segment of the week, or vice-versa.

McGee and Reis (2012) recommended a hybrid learning approach whereby in-class time is learner-centered, active and collaborative, with more time spent on problem-solving, group work, or for an interactive learning activity. Out-of-class time could be comprised of watching videos, posting discussion responses and replies to others, reading or researching, collaborative assignments, or other interactive work.

Active Learning

Also, ponder how best the learning activities promote learner-learner and learner-instructor interaction, to engage and motivate students in meaningful ways and to deepen learning. In the online portion of the course, learner-instructor interactions should be regular, substantive, and initiated by faculty (Klotz & Wright, 2017). Learner-learner interaction should also be present. Examples of learning activities that promote interaction include discussion boards (audio, video, written), role play, debates, faculty-recorded lectures or demonstrations, reacting to the past (RTTP), poster presentation sessions, panel discussions, think/pair/share, one-minute papers (student feedback, burning questions, key point summarization), ‘find someone who’, collaborative work groups, peer reviews, jigsaw, games, etc. Future BYTES will underscore designing student activities for active learning.

Course Design

Update the course design document to outline which activities and assessments will be on the ground or online. Use grading rubrics and learning activity or assessment-specific instructions, especially for the online portion of the course. Many student questions can be prevented by anticipating them when constructing the overall course design. Estimate the amount of time that students should allocate to each learning activity and publish this information as part of the course map (George-Walker & Keeffe, 2010).

Student Readiness for Hybrid Learning

Essential to student readiness in the online portion of a blended course is for faculty to communicate their expectations and provide specific examples to show students how to be successful (Luna & Winters, 2017). One suggestion is to spend in-class time reviewing the online component requirements, which reinforces student understanding, establishes a sense of comfort, and reduces stress (Futch, DeNoyelles, Thompson, & Howard, 2016). Another way that faculty can prepare students for hybrid learning is to offer regular, prompt, and specific feedback. Constructive and positive feedback bridges the gap between learning objectives (the plan) with learning outcomes (the results). Students can make learning adjustments and/or corrections more quickly the sooner that faculty provide feedback.

Course Technology

Students must have a sufficient understanding of the course technology to be online ready in the short and long runs (Tuapawa, 2016). Consider posting how-to videos and tutorials, FAQ information, and taking a few minutes of face-to-face class time to review the relevant technology. Run technology tests or simulations with your students in advance of the official delivery need. Host a Q&A forum in EduCat devoted specifically to tech questions. Post the Help Desk contact information in the course room. Offer upfront guidance as to what types of tech questions should be posed to the Help Desk, the internet provider, and/or you, as the faculty member.

Time Management

Time management and organizational skills are lead indicators of student success in the online learning environment. Offer your students advice with respect to managing the course workload. Consider publishing a weekly plan related to the requirements along with their expected time requirements. This distribution can take place as an EduCat announcement on in class. Another idea is to ask former students who were successful in the hybrid course to share their best practices with your current students.

Sense of Network and Community

Build a sense of network and community into the course design. Students who have a sense of belonging or place are more engaged and motivated. They realize superior learning outcomes and higher retention and persistence rates as opposed to those courses without a support system (Nurcan & Tugba, 2018). To develop a virtual community space, communicate frequently with your students. Consider incorporating activities into the course from the start so that students get to know one another and you, as faculty. Answer questions promptly and provide support when needed. Be available for your students and stay connected with them, especially in the online segment of the hybrid course. Place a non-graded discussion forum in the course simply for the purpose of maintaining a learning community.

All of the design work discussed in this newsletter should take place before the start of the course. Central to a delivering an effective hybrid course is purposeful design; otherwise, the cart is placed before the proverbial horse.

Let’s continue to weather this COVID-19 storm - together. Please know that I am always here, as are the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) team, and the Teaching and Learning Scholar, Lisa Flood, to support our faculty at large with distance learning delivery or online teaching and learning. I am only an email, phone call, or Zoom meeting / Google Hangout away: sboyerda@nmu.edu or (906) 227-1805. I will deliver one-on-one training sessions to full department offerings and anything in between. PLEASE reach out to me if I can be of any help whatsoever.

Please be watching your email in the coming days and weeks for more distance delivery resources and professional development sessions from the Center for Teaching and Learning and the Global Campus.

Our blended learning miniseries continues over the next several weeks to include:

Part III 6/22/2020: Hybrid Course Delivery Strategies

Part IV 6/29/2020: Hybrid Course Assessment Strategies

Stay healthy, safe, and Yooper strong my faculty friends.

Best regards,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar

*************************************************************************************************************

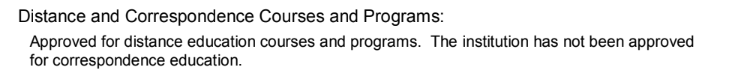

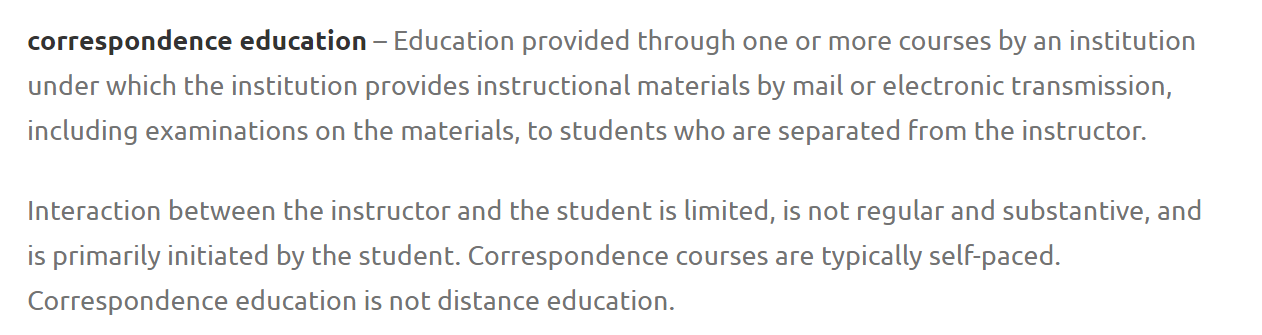

The Global Campus has adopted the Seven Principles to serve as the framework for online course delivery standards (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). The Quality Matters (QM®) peer-reviewed quality assurance program has been adopted to evaluate course design rigor. Both methodologies align with and parallel the call for learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interactions to promote active learning engagement (QM 5.2). For HLC accreditation purposes, all online courses must include learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interaction (regular and substantive, initiated by the instructor) because correspondence courses are not permitted.

For more information on the Global Campus online course requirements or the SoTL related to them, and/or to curate a conversation about high impact teaching design and delivery practices in your online courses, please reach out to Stacy, the Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar via email onlreview@nmu.edu or telephone (906) 227-1805.

Faculty are encouraged to contribute to the ONLINE BYTE OF THE WEEK. Please email Stacy at sboyerda@nmu.edu with your ideas.

REFERENCES

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3-7.

Futch, L. S., DeNoyelles, A., Thompson, K., & Howard, W. (2016). Comfort as a critical success factor in blended learning courses. Online Learning, 20(3), 1-19.

George-Walker, L. D., & Keeffe, M. (2010). Self-determined blended learning: A case study of blended learning design. Higher Education Research & Development, 29(1), 1-13.

Klotz, D. E., & Wright, T. A. (2017). A best practice modular design of a hybrid course delivery structure for an executive education program. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovation Education, 15(1), 25-41.

Luna, Y. M., & Winters, S. A. (2017). Why did you blend my learning? A comparison of student success in lecture and blended learning Introduction to Sociology courses. Teaching Sociology, 45(2), 116-130.

McGee, P., & Reis, A. (2012). Blended course design: A synthesis of best practices. Online Learning, 16(4), 7-22.

Nurcan, A., & Tugba, T. (2018). The impact of motivation and personality on academic performance in online and blended learning environments. Educational Technology & Society, 21(3), 35-47.

Standards from the Quality Matters (QM) Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. Retrievedfromhttps://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Tuapawa, K. (2016). Interpreting experiences of students using online technologies to interact with students in

Vol. 1, Issue 44, June 8, 2020

Through June, the BYTE presents a four-part miniseries on the topic of blended or hybrid learning. This week, we begin with a definition of what a hybrid course is, the benefits of hybrid learning for our students and faculty, and how to begin the process of transforming learning activities to be online ready.

6/15/2020: Hybrid Course Design Strategies

6/22/2020: Hybrid Course Delivery Strategies

6/29/2020: Hybrid Course Assessment Strategies

On June 2, the President’s Office communicated, as part of the “Return to Work Document, Buyouts, and More” email, the following via the Course Scheduling Model Approved (for Fall 2020) section.

“Nearly all courses will have a face-to-face component, although some use of technology will be used in many where it is impossible to fit all of the students of a class section in the classroom and maintain social distancing. This might mean students alternating days of face-to-face with electronic instruction or one of several other creative solutions. Most courses with 20 or fewer students will be able to all be in a classroom and meet social distancing protocols. It will take about 3-4 weeks to complete the room scheduling and then faculty members and students will be informed about where each class is assigned.”

One of the “several other creative solutions” that you may be contemplating for fall course offerings is the hybrid or blended learning model.

What is a Hybrid Course?

A hybrid course combines both on-campus and online learning environments (Buzzetto & Sweat, 2006; Masie 2002). Conventional brick and mortar learning activities are transformed to be e-delivered. To achieve the ideal learning blend, pedagogic strategies must be implemented by careful design to align with both classroom and online environments. Active learning is an integral component of the online segment of a blended course design and a QM best practice (learner-learner, learner-instructor, and learner content). Blended courses are most engaging when on-the-ground and online learning activities complement one another (Liu, Peng, Zhang, Hu, Li, & Yan, 2016).

Northern Michigan University Definition of a Hybrid Course (Academic Affairs policy)

Hybrid A: Face-to-Face Hybrid (designated 70-79)

Online/Web-based activity (either synchronous or asynchronous) is mixed with face-to-face classroom meetings, replacing a significant percentage, but not all required face-to-face instructional activities. Half (50%) or more of the course meeting time (but not all) is scheduled for in-person, face-to-face instruction either at the NMU main campus or at a satellite campus or designated meeting space. The web-based component of the course is typically delivered in an asynchronous format whereby students can complete all course requirements without any required synchronous web-based meeting times for any graded or non-graded requirements. However, if synchronous online activity is required (whereby students must be online at specific times and dates), the synchronous times should be explicitly listed or designated as “to be determined by student preferences” when courses are submitted to the registrar.

Hybrid B: Online Hybrid (designated 80-89)

Online/Web-based activity (both synchronous and asynchronous) is mixed with face-to-face classroom meetings, replacing a significant percentage, but not all required face-to-face instructional activities. Less than 50% of the course meeting time is scheduled for in-person, face-to-face instruction either at the NMU main campus or at a satellite campus or designated meeting space. The web-based component of the course is typically delivered in an asynchronous format whereby students can complete all course requirements without any required synchronous web-based meeting times for any graded or non-graded requirements. However, if synchronous online activity is required (whereby students must be online at specific times and dates), the synchronous times should be explicitly listed or designated as “to be determined by student preferences” when courses are submitted to the registrar.

Benefits of Hybrid Courses

Blended courses impart the flexibility, convenience, and time management of online learning without altogether compromising the face-to-face interaction of a traditional classroom learning experience. By incorporating technologies into the classroom, faculty are able to identify underperforming students more quickly as opposed to those that do not (Bernard, Borokhovski, Schmid, Tamim, & Abrami, 2014; Chingosa, Griffiths, Mulhern, Spies, 2017). Hybrid courses benefit students who are underrepresented or not academically prepared, improving retention and persistence rates (Sithole, Chiyaka, & McCarthy, 2017). How popular are hybrid courses? A pre-COVID 19 statistic, blended course offerings have been adopted by nearly 80% of all public institutions of higher learning in the United States (U.S. Department of Education, 2009). This course design and delivery modality is and will continue to grow in acceptance in the short run COVID-19 pandemic planning process and beyond.

How to Transform Learning Activities to be Online Ready

In order to redesign a portion (50% or otherwise of the weekly course requirements) of a face-to-face course to be delivered online, begin with the learning objectives. Distinct agreement is mined from SoTL in that the most effective course design begins with clearly defined and measurable course learning objectives (Henrich & Sieber, 2009; Kim, Bonk, & Oh, 2008; Precel, Eshet-Alkalai, & Alberton, 2009). Recall that learning objectives are what we want our students to be able to do or know by the end of a unit or units and/or the overall course, the plan for and expectations of learning. Learning objectives should be measurable and use action verbs for assessment measurement purposes (QM 2.1).

Create a syllabus that includes a blueprint that charts a course for the entire semester and the division of labor, so to speak between online and on the ground learning (Hensley, 2005). Consider creating a design document for the course, in total, and for each learning subunit.

![]()

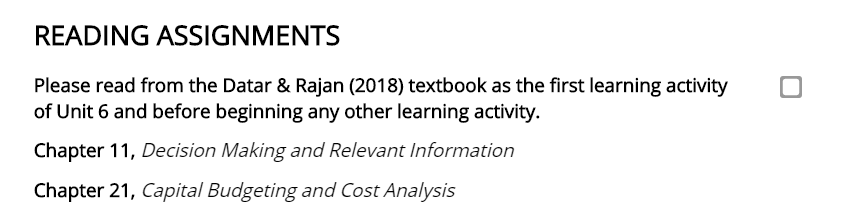

Remember, module and/or unit-level learning objectives should align with overall course learning objectives. Provide students with an estimated time required for each learning activity, assignment, or assessment.

Let’s continue to weather this COVID-19 storm - together. Please know that I am always here, as are the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) team, and the Teaching and Learning Scholar, Lisa Flood, to support our faculty at large with distance learning delivery or online teaching and learning. I am only an email, phone call, or Zoom meeting / Google Hangout away: sboyerda@nmu.edu or (906) 227-1805. I will deliver one-on-one training sessions to full department offerings and anything in between. PLEASE reach out to me if I can be of any help whatsoever.

Please be watching your email in the coming days and weeks for more distance delivery resources and professional development sessions from the Center for Teaching and Learning and the Global Campus.

Stay healthy, safe, and Yooper strong my faculty friends.

Best regards,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar

Read Vol. 1, Issue 45

*************************************************************************************************************

The Global Campus has adopted the Seven Principles to serve as the framework for online course delivery standards (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). The Quality Matters (QM®) peer-reviewed quality assurance program has been adopted to evaluate course design rigor. Both methodologies align with and parallel the call for learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interactions to promote active learning engagement (QM 5.2). For HLC accreditation purposes, all online courses must include learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interaction (regular and substantive, initiated by the instructor) because correspondence courses are not permitted.

For more information on the Global Campus online course requirements or the SoTL related to them, and/or to curate a conversation about high impact teaching design and delivery practices in your online courses, please reach out to Stacy, the Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar via email onlreview@nmu.edu or telephone (906) 227-1805.

Faculty are encouraged to contribute to the ONLINE BYTE OF THE WEEK. Please email Stacy at sboyerda@nmu.edu with your ideas.

REFERENCES

Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Schmid, R. F., Tamim, R. M., & Abrami, P. C. (2014). A meta-analysis of blended learning and technology use in higher education: From the general to the applied. Journal of Computers in Higher Education, 26, 87–122.

Buzzetto, N. A., & Sweat, R. (2006). Hybrid learning defined. Journal of Information Technology Education, 5(1), 153-156.

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3-7.

Chingosa, M. M., Griffiths, R. J., Mulhern, C., & Spies, R. R. (2017). Interactive online learning on campus: Comparing students’ outcomes in hybrid and traditional courses in the university system of Maryland. The Journal of Higher Education, 88(2), 210-233.

Henrich, A., & Sieber, S. (2009). Blended learning and pure e-learning concepts for information retrieval: Experiences and future directions. Information Retrieval, 12(2), 117-147.

Hensley, G. (2005). Creating a hybrid college course: Instructional design notes and recommendations for beginners. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 1(2).

Kim, K. J., Bonk, C. J., & Oh, E. J. (2008). The present and future state of blended learning in workplace learning settings in the United States. Performance Improvement, 47(8), 5-16.

Liu, Q., Peng, W., Zhang, F., Hu, R., Li, Y., & Yan, W. (2016). The effectiveness of blended learning in health professions: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(1). doi:10.2196/jmir.4807

Masie, E. (2002). The ASTD e-Learning Handbook. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Precel, K., Eshet-Alkalai, Y., & Alberton, Y. (2009). Pedagogical and design aspects of a blended learning course. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 10(2).

Sithole, A., Chiyaka, E. T., & McCarthy, P. (2017). Student attraction, persistence and retention in STEM programs: Successes and continuing challenges. Higher Education Studies, 7(1).

Standards from the Quality Matters (QM) Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. Retrieved fromhttps://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development. (2009). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. Washington, D.C.

Vol. 1, Issue 43, June 1, 2020

For faculty who are considering teaching online this fall who are not yet online “qualified,” the BYTE announces the next offering of the “Teaching Online @ NMU” course:

July 6, 2020 – July 31, 2020

What is the Teaching Online @ NMU Course?

"Teaching Online @ NMU” is a four-week, instructor-facilitated course designed to prepare Northern Michigan University faculty to teach online courses. It introduces techniques and tools for leading online courses at NMU, as well as related policies, processes, and resources.

To be distance qualified, anyone teaching an online course must have completed required professional development on online teaching competencies in four general categories:

- The NMU online teaching environment (e.g., methods for engaging students, instructor resources)

- NMU learning management system basics

- Managing and delivering online course content

- Grading and evaluation

This course focuses on the delivery, not design, of online courses. There is no formal prerequisite for the course. The assumption is that those enrolled either already have experience with online course design or are teaching in a program where the department has supplied a standardized online course.

Please visit the following link to register: https://www.nmu.edu/ctl/registration

Faculty who have previously taught online at NMU and are not yet “qualified,” can, instead, complete a self-paced tutorial, “Teaching Online @ NMU Overview,” delivered through NMU’s learning management system. Alternatively, faculty who have previously taught online may choose to take the “Teaching Online @ NMU” course, discussed above, designed for new online faculty.

With approval from Academic Affairs, faculty who have previously taught online at another institution may be permitted to complete the self-paced tutorial instead of the four-week course. Alternative professional development may be approved by Academic Affairs.

Let’s continue to weather this COVID-19 storm - together. Please know that I am always here, as are the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) team, and the Teaching and Learning Scholar, Lisa Flood, to support our faculty at large with distance learning delivery or online teaching and learning. I am only an email, phone call, or Zoom meeting / Google Hangout away: sboyerda@nmu.edu or (906) 227-1805. I will deliver one-on-one training sessions to full department offerings and anything in between. PLEASE reach out to me if I can be of any help whatsoever.

Please be watching your email in the coming days and weeks for more distance delivery resources and professional development sessions from the Center for Teaching and Learning and the Global Campus.

Stay healthy, safe, and Yooper strong my faculty friends.

Best regards,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar

Read Vol. 1, Issue 44

*************************************************************************************************************

The Global Campus has adopted the Seven Principles to serve as the framework for online course delivery standards (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). The Quality Matters (QM®) peer-reviewed quality assurance program has been adopted to evaluate course design rigor. Both methodologies align with and parallel the call for learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interactions to promote active learning engagement (QM 5.2). For HLC accreditation purposes, all online courses must include learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interaction (regular and substantive, initiated by the instructor) because correspondence courses are not permitted.

For more information on the Global Campus online course requirements or the SoTL related to them, and/or to curate a conversation about high impact teaching design and delivery practices in your online courses, please reach out to Stacy, the Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar via email onlreview@nmu.edu or telephone (906) 227-1805.

Faculty are encouraged to contribute to the ONLINE BYTE OF THE WEEK. Please email Stacy at sboyerda@nmu.edu with your ideas.

REFERENCES

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3-7.

Standards from the Quality Matters (QM) Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. Retrievedfromhttps://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Vol. 1, Issue 42, May 25, 2020

Today, on this Memorial Day, we remember those who lost their lives in the service of their people and countries. To everyone who made the ultimate sacrifice, we thank you and celebrate your bravery and courage. Your legacy will live on in infamy.

Trends in Student Academic Stress

Twenty years ago, one out of every ten students self-reported as in need of mental health services. Today, one in three students demand support. Of the 63,000 college students surveyed as part of the American College Health Association (2018) study, nearly 65% of college students reported overwhelming anxiety in the last year, 60% described intense concern and unease, and 40% conveyed symptoms of depression severe enough to impede regular function. In addition, 50% of college students rated their mental health as poor and one in five students reported thoughts of suicide in the last year. Approximately 39% of college students will experience a mental health issue (pre-COVID results).

The Center for Collegiate Mental Health (2019) has recently identified that anxiety and depression are the most common concerns of students seeking counseling services. Student self-reports of anxiety and depression are significantly on the rise. Particularly concerning is that the rate of threat-to-self for students seeking counseling services has increased for the eighth year in a row.

Campuses are struggling to respond to the critical escalation of student mental health needs and keep pace with a pandemic-like demand. Colleges and universities across the country are undertaking an immense effort to evaluate how to increase outreach to students and expand counseling services resources and other support services (Beiter, Nash, McCrady, Rhoades, Linscom, Clarahan, & Sammut, 2015; Delucia-Waack, Athalye, Floyd, Howard, & Kuszczak, 2011; Kumaraswamy, 2013; Mahmoud, Staten, Hall, & Lennie, 2012).

Mental health issues can trigger damaging effects to academic performance. For one, test anxiety has been linked to lower grade point averages (GPA) in both graduate and undergraduate students (Chapell, Blanding, Silverstein, Takahashi, Newman, Gubi, & McCann, 2005). Depression has been found to adversely impact assessment exam scores, overall academic performance, class attendance, participation, engagement, and student retention rates (Andrews & Wilding, 2004; Bohannon, Clapsaddle, & McCollum, 2019; Stocker & Gallagher, 2019).

These statistics are alarming. Yet, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is further eroding the mental health of our students. This week, the BYTE offers online course design and delivery strategies to reduce student academic stress during an accelerated summer term.

Strategies to Reduce Student Academic Stress in an Accelerated Online Summer Course

Accelerated summer terms provide our students with the opportunity to complete coursework with an abbreviated schedule outside of the traditional 15-week academic calendar. During summer months, students often simultaneously work a part-time or full-time job while juggling course work and other commitments. The sheer nature of handling multiple, sometimes conflicting, priorities like a job or a summer course is a challenge for the best of us. However, a 6-week fast-tracked course that emphasizes the same learning objectives as its 15-week counterpart is prime for an exponential escalation and intensification of student academic stress.

In an attempt to counteract the debilitating pressure and tension that can result from an accelerated course, below is an abridged list of strategies to reduce student academic stress in an accelerated summer online course.

- Initiate class communications often, perhaps even daily.

- Stay in tune with the class to promote student engagement and reduce isolation and stress.

- Be positive; construct a learning community that promotes social togetherness and support (Wood & Tarrier, 2010).

- Provide regular, meaningful feedback to students and grade assignments before other assignments are due to bridge the gap between learning objectives (what students should be able to do or learn by the conclusion of a course) with learning outcomes (actual results).

- Use detailed but easy-to-follow grading rubrics to clarify assessment requirements.

- Consider hosting regular, weekly Zoom meetings (virtual office hours) for student questions related to course content, assignments, etc.

- Clearly communicate assignment and assessment requirements and deliverables.

- Consider posting exemplars to help students understand assignment requirements.

- Incorporate flexibility by offering an assignment “do over” or low-stakes extra credit.

- Design content to ground learning in a real-world context.

- Publish exam study guides to help students identify priority areas of focus.

- Offer partial credit instead of all-or-nothing grading.

- Combine a calming (green), yet energizing (orange) color scheme in the design of your online courses while being mindful of those with vision impairment.

- Keep the course navigation simple and consistent each module or unit so that students do not have to relearn the location of course essentials week after week.

- Chunk course content into micro-bites. With smaller bites to chew, students gain content confidence more quickly and are more easily motivated to move forward.

- Impart humor into the class to relieve stress.

- Reach out to struggling students with guidance to improve their academic performance.

- Publish a best practices guideline to complete weekly course activities with anticipated time requirements.

- For term-length or larger, high-stakes projects, provide students with a midway check-in period or the opportunity to turn in a full or partial draft, or submit an abbreviated presentation recording for interim feedback.

- Encourage students to meditate as a mechanism to stay focused and reduce stress. Embed a meditation website link in the course or host your own live student meditation sessions.

Let’s continue to weather this COVID-19 storm - together. Please know that I am always here, as are the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) team, and the Teaching and Learning Scholar, Lisa Flood, to support our faculty at large with distance learning delivery or online teaching and learning. I am only an email, phone call, or Zoom meeting / Google Hangout away: sboyerda@nmu.edu or (906) 227-1805. I will deliver one-on-one training sessions to full department offerings and anything in between. PLEASE reach out to me if I can be of any help whatsoever.

Please be watching your email in the coming days and weeks for more distance delivery resources and professional development sessions from the Center for Teaching and Learning and the Global Campus.

Stay healthy, safe, and Yooper strong my faculty friends.

Best regards,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar

Read Vol. 1, Issue 43

*************************************************************************************************************

The Global Campus has adopted the Seven Principles to serve as the framework for online course delivery standards (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). The Quality Matters (QM®) peer-reviewed quality assurance program has been adopted to evaluate course design rigor. Both methodologies align with and parallel the call for learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interactions to promote active learning engagement (QM 5.2). For HLC accreditation purposes, all online courses must include learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interaction (regular and substantive, initiated by the instructor) because correspondence courses are not permitted.

For more information on the Global Campus online course requirements or the SoTL related to them, and/or to curate a conversation about high impact teaching design and delivery practices in your online courses, please reach out to Stacy, the Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar via email onlreview@nmu.edu or telephone (906) 227-1805.

Faculty are encouraged to contribute to the ONLINE BYTE OF THE WEEK. Please email Stacy at sboyerda@nmu.edu with your ideas.

REFERENCES

American College Health Association (2018). National College Health Assessment (NCHA) Fall 2018 Reference Group Data Report. Retrieved from https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-II_Fall_2018_Reference_Group_Executive_Summary.pdf

Andrews, B., & Wilding, J. M. (2004). The relation of depression and anxiety to life-stress and achievement in students. British Journal of Psychology, 95(4), 509-521.

Beiter, R., Nash, R., McCrady, M., Rhoades, D., Linscomb, M., Clarahan, M., & Sammut, S. (2015). The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 173, 90-96.

Bohannon, L., Clapsaddle, S., & McCollum, D. (2019). Responding to college students who exhibit adverse manifestations of stress and trauma in the college classroom. FIRE: Forum for International Research in Education, 5(2), 66-78.

Center for Collegiate Mental Health (CCMH), (2019). Penn State 2018 Annual Report. Retrieved from https://sites.psu.edu/ccmh/files/2019/01/2018-Annual-Report-1-15-2018-12mzsn0.pdf

Chapell, M. S., Blanding, Z. B., Silverstein, M. E., Takahashi, M., Newman, B., Gubi, A., & McCann, N. (2005). Test anxiety and academic performance in undergraduate and graduate students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(2), 268-274.

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3-7.

Delucia-Waack, J., Athalye, D., Floyd, K., Howard, M., & Kuszczak, S. (2011). Outreach for college students related to mood and anxiety management. In T. Fitch, J. L. Marshall, T. Fitch, & J. L. Marshall (Eds.), Group work and outreach plans for college counselors. (pp. 271-285). Alexandria, VA, US: American Counseling Association.

Kumaraswamy, N. (2013). Academic stress, anxiety and depression among college students-a brief review. International review of social sciences and humanities, 5(1), 135-143.

Lambert, S. F., Lambert, J. C., & Lambert, III, S. J. (2014). Distressed college students following traumatic events. Ideas and research you can use. VISTAS 2014.

Mahmoud, J. S. R., Staten, R. T., Hall, L. A., & Lennie, T. A. (2012). The relationship among young adult college students’ depression, anxiety, stress, demographics, life satisfaction, and coping styles. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33(3), 149-156.

Standards from the Quality Matters (QM) Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. Retrievedfromhttps://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Stocker, S. L., & Gallagher, K. M. (2019). Alleviating anxiety and altering appraisals: Social-emotional learning in the college classroom. College Teaching, 67(1), 23-35.

Wood, A. M., & Tarrier, N. (2010). Positive clinical psychology: A new vision and strategy for integrated research and practice. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 819-829.

Vol. 1, Issue 41, May 18, 2020

The BYTE is back! During my recent hiatus, I researched teaching and learning scholarship: emerging, seminal, and everything in between, the results of which I will share via our Global Campus newsletter throughout the summer and during upcoming professional development offerings expected this fall.

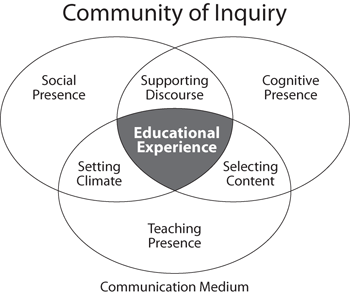

Our first summer session online courses begin this week. As such, consider the adoption of an icebreaker learning activity during the first days of your online courses to engage learners right from the start and encourage teaching, social, and cognitive presences. The literature that supports this instructional strategy is embedded within the Community of Inquiry framework (Garrison, 2000, 2011; Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000, 2010; Garrison & Arbaugh, 2007; Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005; Garrison, Cleveland-Innes, & Fung, 2010). The educational experience of learning is theorized to stem from the interconnection between three distinct presences: teaching, social, and cognitive.

Figure 1

The Community of Inquiry Framework

Note. This figure represents the Community of Inquiry framework as originally published in Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education model. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105.

Teaching Presence

Broadly speaking, teaching presence is the outcome of a well-designed and delivered course. A majority of the BYTES published over the last year and the professional development sessions presented by the Global Campus emphasized approaches to create and facilitate teaching (and social) presence. The next several sections summarize the differences between online course design and delivery.

Course Design

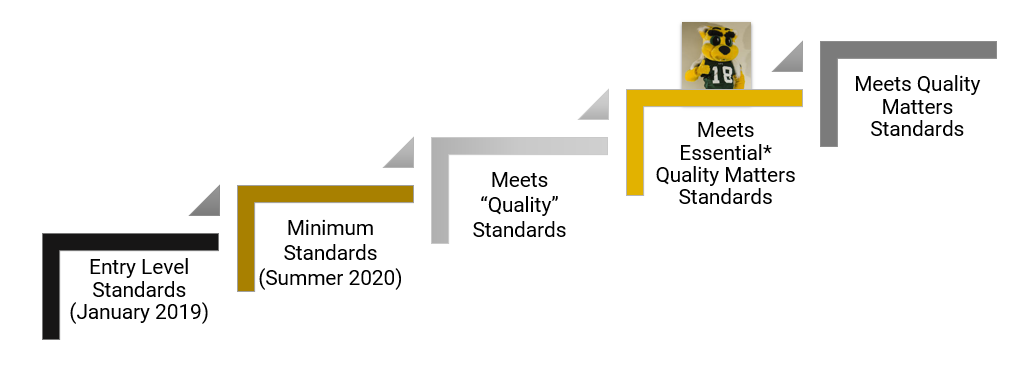

Online course design includes the faculty’s role in the planning and development of a course, as well as in the conception and construction of all course components (syllabus, learning objectives, assignments, instructional materials, activities, assessments, accessibility, grading, technology, learner support, and opportunities for interaction). With course design, think Quality Matters (QM), the well-respected peer-reviewed set of standards employed to determine the quality of the design of online and blended courses, based on research-supported and published generally accepted teaching practices, and the foundation that supports the Global Campus Online Course Design Review Standards.

An optimal way to either build or reinforce your expertise with respect to Quality Matters is to enroll in the Global Campus-sponsored Online Teaching Fellows I and II programs, facilitated by the Center for Teaching and Learning team. The Summer 2020 Online Teaching Fellows (OTF) I program began last Thursday. Now, OTF is 100% online. This was our largest response yet! Faculty demand exceeded our usual class size capacity. The cohort size, typically a cap of 15-16, was increased to 20 to accommodate faculty demand and even then, some faculty applications were deferred to a future term. More information regarding the next Online Teaching Fellows I program offering is forthcoming.

Course Delivery

Course delivery is the teaching of the course, itself. Chickering and Gamson (1987) offered seven principles to promote teaching presence during the act and art of teaching including: 1) encourages contact between students and faculty, 2) develops reciprocity and cooperation among students, 3) encourages active learning, 4) gives prompt feedback, 5) emphasizes time on task, 6) communicates high expectations, and 7) respects diverse talents and ways of learning. Last summer, I devoted an 8-week BYTE series to online course delivery and each of these principles. Archived copies of the Online BYTE as found here: https://www.nmu.edu/online/online-byte-week

Social Presence

Social presence, or the degree to which one is perceived as a human being or real person in the virtual learning space, occurs through interaction (learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content). Interaction enables the opportunity for participants (faculty and students) to project themselves in such a way as to establish connectedness and build an online learning community (Swan & Shih, 2005). Students make up for the lack of visual and auditory cues through indicators of social presence. These cues can make all the difference between students who are engaged and motivated or those who feel isolated, disassociated, and unmotivated (Durrington, Berryhill, & Swafford, 2006).

Cognitive Presence

Quintessential to learning, cognitive presence (also known as thinking presence), is the holistic process of how students interact with course content, engage in critical thinking, reflect upon concepts, connect with and apply foundational knowledge or prior experiences to solve problems and develop greater understanding (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2001). Faculty play a leading role in the design and delivery of learning activities to foster cognitive presence (Archibald, 2010). Consider the 3 R’s of student engagement to promote cognitive presence when designing and delivering your courses: 1) relevance, 2) rigor, and 3) relationships (Littky & Grabelle, 2004). Relevance is the act of inspiring curiosity in our students with activities that establish connections to prior learning. Rigor is challenging students to solve problems that are personally meaningful to them. Relationships are formed when faculty design a learning environment where students work collaboratively with one another and with the faculty, themselves, to foster a community of inquiry.

Encouraging Teaching, Social, and Cognitive Presences through Introductory Activities

Introductory activities can help to establish a sense of community, break down social barriers, start conversations, build a collaborative network, introduce topics and content, and set the tone. Learners and faculty, alike, should participate in the introductory activities. Students should get to know each other and you, as their professor. Before creating an icebreaker, be sure that you establish a purpose for the activity, define the learning objectives of it, and clearly communicate the expectations to students.

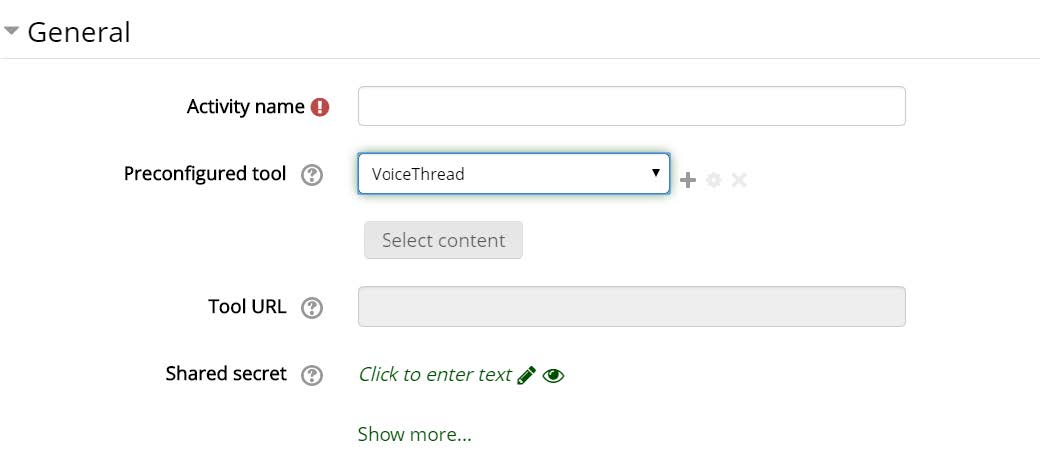

Here are a few ideas to springboard your online course introductory activities. Consider incorporating VoiceThread, discussion boards, chats, or Zoom technologies to facilitate them.

- Unique and Shared: Place students into groups of 4-5 and encourage them to discover what they have in common along with any interesting or unique experiences or attributes that sets them each apart. Then, at the end of the week after the group has conferred, they can report out to the class at large (think/pair/share).

- Show and Tell: Provide students with the opportunity to showcase something that represents what interests them most: a topic, object, etc. VoiceThread works well with this type of activity.

- Mix and Mingle: Set up a discussion forum, VoiceThread, or a synchronous Zoom meeting and let students walk around, so to speak, to meet one another, share their backgrounds, and/or any apprehensions prior to starting the class.

- One Word at a Time: Create a series of sentences, equations, cases, etc. based off of prerequisite course content and ask students to fill in the blanks. Gamify it, make it a competition, and provide rewards. Encourage students to reflect upon prior learning before the class kicks off for the term.

- Photo Shop: Have students take a picture from their windows and post them in the course room. Have other students guess where they are.

- The Noun Game: Ask students to offer 8-10 nouns that represent them and describe why they symbolize who they are. Then, students are to find a noun provided by another student that most resonates with them and explain why. In addition, students should connect with someone with whom two nouns are in common. Discussion forums are optimal for the noun game.

- Name Game: Students create a mnemonic of their name and use it to describe themselves.

Let’s continue to weather this COVID-19 storm - together. Please know that I am always here, as are the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) team, and the Teaching and Learning Scholar, Lisa Flood, to support our faculty at large with distance learning delivery or online teaching and learning. I am only an email, phone call, or Zoom meeting / Google Hangout away: sboyerda@nmu.edu or (906) 227-1805. I will deliver one-on-one training sessions to full department offerings and anything in between. PLEASE reach out to me if I can be of any help whatsoever.

Please be watching your email in the coming days and weeks for more distance delivery resources and professional development sessions from the Center for Teaching and Learning and the Global Campus.

Have a fantastic start to the summer term! Stay healthy, safe, and Yooper strong my faculty friends.

Best regards,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar

Read Vol. 1, Issue 42

*************************************************************************************************************

The Global Campus has adopted the Seven Principles to serve as the framework for online course delivery standards (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). The Quality Matters (QM®) peer-reviewed quality assurance program has been adopted to evaluate course design rigor. Both methodologies align with and parallel the call for learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interactions to promote active learning engagement (QM 5.2). For HLC accreditation purposes, all online courses must include learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interaction (regular and substantive, initiated by the instructor) because correspondence courses are not permitted.

For more information on the Global Campus online course requirements or the SoTL related to them, and/or to curate a conversation about high impact teaching design and delivery practices in your online courses, please reach out to Stacy, the Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar via email onlreview@nmu.edu or telephone (906) 227-1805.

Faculty are encouraged to contribute to the ONLINE BYTE OF THE WEEK. Please email Stacy at sboyerda@nmu.edu with your ideas.

REFERENCES

Archibald, D. (2010). Fostering the development of cognitive presence: Initial findings using the community of inquiry survey instrument. Internet and Higher Education, 13, 73 – 74.

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3-7.

Durrington V. A., Berryhill, A., & Swafford, J. (2006). Strategies for enhancing student interactivity in an online environment. College Teaching, 54(1), 190-193.

Garrison, D. R. (2000). Theoretical challenges for distance education in the 21st century: A shift from structural to transactional issues. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 1(1). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/viewArticle/2

Garrison, D. R. (2011). E‐Learning in the 21st century: A framework for research and practice (2nd ed.). London, UK: Routledge.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text‐based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. Internet and Higher Education, 2(2–3), 87-105.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2010). The first decade of the community of inquiry framework: A retrospective. Internet and Higher Education, 13, 5-9.

Garrison, D. R., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2007). Researching the community of inquiry framework: Review, issues, and future directions. Internet and Higher Education, 10(3), 157-172.

Garrison, D. R., & Cleveland‐Innes, M. (2005). Facilitating cognitive presence in online learning: Interaction is not enough. American Journal of Distance Education, 19(3), 133-148.

Garrison, D. R., Cleveland‐Innes, M., & Fung, T. S. (2010). Exploring causal relationships among teaching, cognitive, and social presence: Student perceptions of the community of inquiry framework. Internet and Higher Education, 13, 31-36.

Littky, D., & Grabelle, S. (2004). The big picture: Education is everyone’s business. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development Standards from the Quality Matters (QM) Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. Retrievedfromhttps://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Swan, K., & Shih, L. F. (2005). On the nature and development of social presence in online course discussions. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 9(3), 115-136.

Vol. 1, Issue 40, April 29, 2020

Greetings NMU faculty and welcome to the ONLINE BYTE OF THE WEEK, a newsletter created to share current scholarship of teaching and learning related to the virtual learning space, online teaching best practices, EduCat learning management system (LMS) tips and techniques, and to spotlight the exceptional means by which we bring cyber learning to life for our students.

The Winter 2020 semester may have proven to be one of the most challenging times in history for higher education. University leaders, faculty, administration, and support personnel found themselves immersed in the floodwaters of a global pandemic, all the while determined to realize their resolute commitment to the education, service, and well-being of our students. Through the ingenuity, tenacity, and innovation of our faculty family, along with the technology and instructional support resources made available to us, we have unequivocally fulfilled our mission to deliver exceptional teaching. We should be extraordinarily proud of what we, as faculty, have accomplished. Our students should be equally, if not more, pleased with their achievements. Humbly speaking, I applaud every one of you for your pedagogic successes despite the virulence and resulting impact we all currently face.

Now, or perhaps after grading has concluded for the term, we should take the time to reflect upon this inconceivable semester to determine how we excelled, how quickly we pivoted in the face of adversity, and perhaps what we can do to improve our course design and delivery effectiveness (Dawson & Hocker, 2020; Thomas, Chie, Abraham, Raj, & Beh, 2014).

“The past, the present, and the future are really one: they are today.” (Harriet Beecher Stowe).

Regularly, we use self-reflection as a continuous improvement tool to identify methods to develop and enhance our teaching. Some of the information we incorporate to inform this introspection includes peer evaluations, student observations, peer observations from the Teaching and Learning Advisory Council (TLAC), the Online Teaching Fellows QM peer review learning activities, and the Global Campus online course design review process.

A few questions that we can ask ourselves in this summative contemplation exercise include the following, all of which start with “Did I” and end with “?”

- Offer regular and substantive learner-instructor and learner-learner interaction opportunities

- Select relevant course materials and activities that promote critical thinking and emphasize social justice and diversity

- Clearly outline measurable learning objectives for the course and each learning module

- Align all course assessments with module-level and course-level learning objectives

- Strive to encourage student motivation throughout the course

- Implement active or service learning techniques to promote student engagement and participation

- Encourage learners to rethink their beliefs, ideas, and thoughts, to allow them a more profound learning experience

- Utilize and embrace technology in the classroom, virtual or otherwise

- Ensure that learners can effectively operate the technology used in class

- Insist that courses are accessibility ready to meet the needs of our students

- Clearly and regularly communicate with my students throughout the entire course via assignment instructions, learning outcomes, grading rubrics, announcements, and the syllabus

- Exhibit enthusiasm in the classroom and take the time to get to know my students

- Provide regular positive, constructive feedback to students to bridge the gap between learning objectives and outcomes

- Set the bar high for student learning but outline a path to reach the goal

- Cover all of the material originally planned for the course

- Measure student learning outcomes using formative and summative techniques to assess student understanding

- Identify a specific section of a course that was most effective, somewhat effective, or least effective and determine why

- Adequately prepare for each unit, module, or class

- Use class time effectively

- Pose goals or objectives for each unit or module and show students how they align with overall course learning objectives

- Provide an outline of the unit or module and stick with the plan

- Convey the purpose of each learning activity

- Encourage student questions and comments

- Use positive reinforcement

- Incorporate student ideas into the class and reword student questions and comments that need adjustment

- Summarize the end of the week, unit, or module

- Use examples to effectively explain course content

- Make explicit statements to draw student attention to certain ideas

- Demonstrate active listening techniques

- Draw nonparticipating students into the class

- Mediate conflict or differences of opinion

- Allow enough time for practice or to complete active learning activities

- Chunk lectures into 5-15 minutes in length

- Have and encourage fun in the learning process

- Emphasize how the knowledge gleaned from class will benefit them in the future

- Encourage participation in events and student, service, and community organizations

Answers to these questions and many others asked during this reflection process can be examined to gauge the effectiveness of our teaching (Malkki, 2012; Ryan, 2011). Faculty may consider attending workshops or professional development sessions such as conferences or those offered by the Global Campus and the Center for Teaching and Learning to expand their pedagogic perspectives. We can collaborate with peers in our own departments or in others to discuss ways to enhance our teaching. Please continue to offer your professional development workshop suggestions to the Global Campus or the CTL. We, sincerely, appreciate your feedback.

This Online Byte is dedicated to my mom, Darlene, who unexpectedly passed away on Easter Sunday. Throughout her life, she encouraged me to reflect on various things from who I am as a person to my career goals. She taught me to live by the “golden rule” and treat others as I, myself, want to be treated. She had a big heart and love of life that was truly inspirational. She did not compromise who she was for anyone. I so admired that about her. Her laugh was infectious and her smile was bright. I will miss you forever, mom.

Let’s continue to weather this COVID-19 storm - together. Please know that I am always here, as are the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) team, and the Teaching and Learning Scholar, Lisa Flood, to support our faculty at large with distance learning delivery or online teaching and learning. I am only an email, phone call, or Zoom meeting / Google Hangout away: sboyerda@nmu.edu or (906) 227-1805. I will deliver one-on-one training sessions to full department offerings and anything in between. PLEASE reach out to me if I can be of any help whatsoever.

Please be watching your email in the coming days and weeks for more distance delivery resources and professional development sessions from the Center for Teaching and Learning and the Global Campus.

Stay healthy, safe, and Yooper strong my faculty friends.

Best regards,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar

Read Vol. 1, Issue 41

*************************************************************************************************************

The Global Campus has adopted the Seven Principles to serve as the framework for online course delivery standards (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). The Quality Matters (QM®) peer-reviewed quality assurance program has been adopted to evaluate course design rigor. Both methodologies align with and parallel the call for learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interactions to promote active learning engagement (QM 5.2). For HLC accreditation purposes, all online courses must include learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interaction (regular and substantive, initiated by the instructor) because correspondence courses are not permitted.

For more information on the Global Campus online course requirements or the SoTL related to them, and/or to curate a conversation about high impact teaching design and delivery practices in your online courses, please reach out to Stacy, the Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar via email onlreview@nmu.edu or telephone (906) 227-1805.

Faculty are encouraged to contribute to the ONLINE BYTE OF THE WEEK. Please email Stacy at sboyerda@nmu.edu with your ideas.

REFERENCES

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3-7.

Dawson, S. M., & Hocker, A. D. (2020). An evidence-based framework for peer review of teaching. Advances in Physiology Education, 44(1).

Malkki, K. (2012). From reflection to action? Barriers and bridges between higher education thoughts and actions. Journal of Studies in Higher Education, 37(1), 33-50.

Ryan, M. (2011). The pedagogical balancing act: Teaching reflection in higher education. Teaching Reflection in Higher Education, 18(2), 144-155.

Standards from the Quality Matters (QM) Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. Retrievedfromhttps://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Thomas, S., Chie, Q. T., Abraham, M., Raj, S. J., & Beh, L. S. (2014). A qualitative review of literature on peer review of teaching in higher education: An application of the SWOT framework. Review of Educational Research, 84(1), 112-159.

Vol. 1, Issue 39, April 20, 2020

Greetings NMU faculty and welcome to the ONLINE BYTE OF THE WEEK, a newsletter created to share current scholarship of teaching and learning related to the virtual learning space, online teaching best practices, EduCat learning management system (LMS) tips and techniques, and to spotlight the exceptional means by which we bring cyberlearning to life for our students.

This week’s BYTE offers steps for a successful semester completion and final exam alternatives for consideration.

Steps for a successful semester wrap-up:

- Develop a plan for how you will administer final exams and/or projects.

- Communicate the plan to your students via EduCat Announcements and/or email (Chang, Beth, & Annice, 2015).

- Communicate the exam requirements such as Respondus Lockdown Browser, Respondus Monitor, Zoom, calculators, etc.

- Request that students share any specific testing needs or concerns with you as soon as possible to allow ample time for resolution (DiPietro, Ferdig, Black, & Preston, 2010).

- Forward an Announcement or email with a reminder about final exams, the day before and day of the exam.

- Provide students with guidance on how to minimize distractions while taking final exams such as closing doors, silencing cell phones, finding a private, quiet area, etc. (Berry & Westfall, 2015).

- Communicate the anticipated day/time when students will receive their final exam and/or project grades.

Final exam alternatives for consideration:

- A case study, reflection or integrated paper, presentation, project, discussion, group exam, or other assignment (Chandler, 1997).

- Provide students with a choice (Universal Design for Learning) between two assessments that measure the same learning objectives. For instance, students could be given the choice between a written assignment and a final exam (Rose & Meyer, 2002).

- Be sure that accommodations have been set in EduCat for those who need them.

The Center for Teaching and Learning (Matt Smock) in conjunction with the Global Campus (Stacy Boyer-Davis) will be hosting a Respondus Monitor training webinar today, Monday, April 20, at 3 pm EST. We will host an overview session on Monday at 3pm via Zoom (password: monitor). Respondus offers live webinars regularly and also has a recording available for their sessions.

As faculty family, let’s continue to weather this COVID-19 storm - together. Please know that I am always here, as are the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) team, and the Teaching and Learning Scholar, Lisa Flood, to support our faculty at large with distance learning delivery or online teaching and learning. I am only an email, phone call, or Zoom meeting / Google Hangout away: sboyerda@nmu.edu or (906) 227-1805. I will deliver one-on-one training sessions to full department offerings and anything in between. PLEASE reach out to me if I can be of any help whatsoever.

Please be watching your email in the coming days and weeks for more distance delivery resources and professional training sessions from the Center for Teaching and Learning and the Global Campus.

Stay healthy, safe, and SISU strong my faculty friends.

Best regards,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar

Read Vol. 1, Issue 40

*************************************************************************************************************

The Global Campus has adopted the Seven Principles to serve as the framework for online course delivery standards (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). The Quality Matters (QM®) peer-reviewed quality assurance program has been adopted to evaluate course design rigor. Both methodologies align with and parallel the call for learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interactions to promote active learning engagement (QM 5.2). For HLC accreditation purposes, all online courses must include learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interaction (regular and substantive, initiated by the instructor) because correspondence courses are not permitted.

For more information on the Global Campus online course requirements or the SoTL related to them, and/or to curate a conversation about high impact teaching design and delivery practices in your online courses, please reach out to Stacy, the Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar via email onlreview@nmu.edu or telephone (906) 227-1805.

Faculty are encouraged to contribute to the ONLINE BYTE OF THE WEEK. Please email Stacy at sboyerda@nmu.edu with your ideas.

REFERENCES

Berry, M. J., & Westfall, A. (2015). Dial ‘D’ for distraction: The making and breaking of cell phone policies in the college classroom. College Teaching, 63(2), 62-71.

Chandler, T. M. (1997). An alternative comprehensive final exam: The integrated paper. Teaching Sociology, 25(2), 183-186.

Chang, C. W., Beth, H., & Annice, M. (2015). You’ve got mail: Student preferences of instructor communication in online courses in an age of advancing technologies. Journal of Educational Technology Development & Exchange, 8(1), 39-48.

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3-7.

DiPietro, M., Ferdig, R., Black, E., & Preston, M. (2010). Best practices in teaching K-12 online: Lessons learned from Michigan virtual school teachers. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 9(3), 10-35.

Luckie, D. B., Rivkin, A. M., Aubrey, J. R., Marengo, B. J., Creech, L. R., & Sweeder, R. D. (2013). Verbal final exam in introductory biology yields gains in student content knowledge and longitudinal performance. Life Sciences Education, 12(3), 515-529.

Rose, D. H., & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Standards from the Quality Matters (QM) Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. Retrievedfromhttps://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Vol. 1, Issue 38, April 12, 2020

Greetings NMU faculty and welcome to the ONLINE BYTE OF THE WEEK, a newsletter created to share current scholarship of teaching and learning related to the virtual learning space, online teaching best practices, EduCat learning management system (LMS) tips and techniques, and to spotlight the exceptional means by which we bring cyberlearning to life for our students.

For this wintry week’s BYTE, I interviewed the Center for Teaching and Learning team and asked them to provide their expert guidance to help faculty navigate the rest of the winter term and finals week via distance delivery and the upcoming online summer term. Matt Smock, Director for the Instructional Design and Technology Unit and Scott Smith, Instructional Technologist, weighed in; their valuable insight, including suggested resources, is summarized below.

- What are the most popular questions that you have received over the last several weeks from faculty in response to distance delivery teaching?

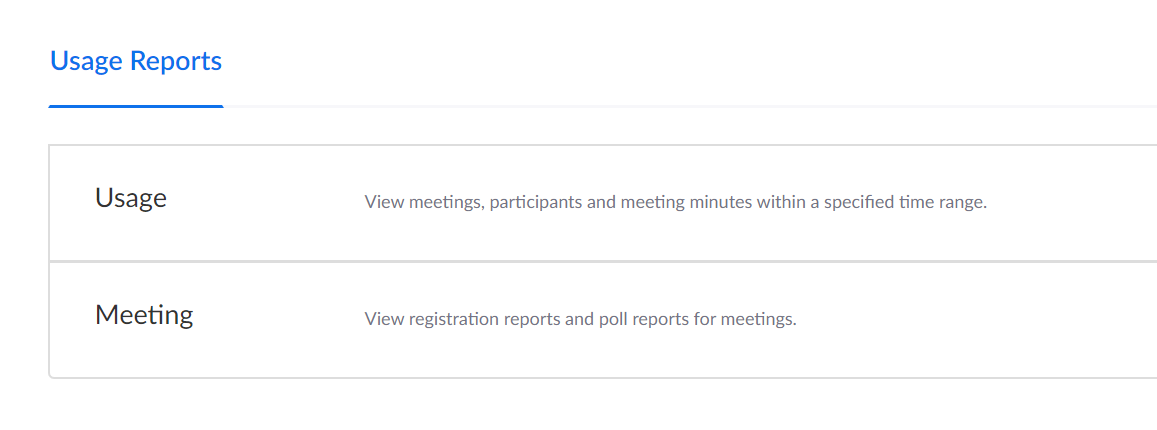

Matt stated that “the number one question area, at least initially, was Zoom, which was new to the majority of the faculty. We’ve also had a lot of questions about recording and posting video lectures. Beyond that, questions have been all over the board, depending on a particular faculty members’ past experience using EduCat and related tools. Some faculty have been learning EduCat basics for the first time, while others are trying more advanced tools for the first time as a way to deliver content that they usually teach face-to-face. Faculty have been doing a great job of adapting and we appreciate how incredibly patient they’ve been during this stressful time.” Scott agreed that Zoom questions were the most asked by faculty, especially how to avoid Zoom bombing and how to set passwords. The CTL published the following resources on Thursday, April 2, regarding those two topics.

More on Preventing Zoom Bombing

Link to Resources to Prevent Zoom Bombing

Additional Information

You may also be interested in reading "Best Practices for Securing Your Virtual Classroom," which Zoom recently posted on their user blog.

- What should faculty know how to do to be successful during finals week with exams and grading via distance delivery?

According to Matt, “Advance planning is key, especially if you’re new to giving exams in an online environment. Don’t try to set up your exam one or two days before it is taking place. We have sessions coming up on EduCat quizzes and the gradebook, and if needed, we will add more. We are also planning to make a new tool, Respondus Monitor, available prior to finals. Monitor deters cheating by recording students as they take EduCat exams through the Lockdown Browser.”

“We’d also like faculty to know that IT has been doing everything possible to optimize the performance of EduCat this semester, and we are optimistic that there won’t be major problems during finals week. However, we also want everyone to be aware that occasional performance issues are possible. We expect the load on the system to be higher than ever before, and some disruptions are possible. Faculty may want to consider allowing their exams to be taken asynchronously during Finals Week, rather than limiting them to a specific period. Academic Affairs will be sending out some guidelines for final exams.”

Scott Smith provided, “get exam requests in early. A week is supposed to be the norm. Become familiar with question formatting so that there is no delay in processing your request. Put no more than 5 questions on a single page of your quiz/exam. The answers save when students go to the next page. If the internet drops, their answers won’t be lost.”

Resources for Quiz (Exam) Formatting

Quiz Settings

Link to Quiz Settings Resources

Quiz Question Format

Link to Quiz Question Format Resources

- What could faculty be doing now to prepare for online courses this summer?

Matt suggested “I’m going to sound like a broken record, but any advance planning now will help ensure a good experience with summer courses. If you are going to be teaching online for the first time, contact your CTL liaison as soon as possible to start talking about planning your course and what you need to be ready for. It isn’t too early to start designing your course, even if you only have limited time to spend on it.”

Resources for Course Requests

Link to Resources for Course Requests

- What additional professional development sessions will be offered this term and into the summer to continue to expand upon and foster high quality distance delivery and online teaching design and delivery?

Matt reported, “I’ve already mentioned our sessions on the quiz and gradebook. I should also mention that we have recorded several of our sessions over the last several weeks, including the one that Amy Barnsley led this past Friday about assessing written work in a distance environment. We will have some informational sessions about Respondus Monitor. EduCat is due for an upgrade before the summer session, so we also plan to have some informational/feedback sessions about its updated interface later this month.”

Scott advocated for the Online Teaching Fellows 1 course, which begins May 14 and the 4-week Teaching Online @ NMU program. More information on it will be shared by the CTL soon.

Link to Online Teaching Fellows I Course Information

Teaching Online @ NMU 4-Week Course:

Link to Teaching Online @ NMU 4-Week Course

Link to Teaching Online @ NMU 4-Week Course Registration

As faculty family, let’s continue to weather this COVID-19 storm - together. Please know that I am always here, as are the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) team, and the Teaching and Learning Scholar, Lisa Flood, to support our faculty at large with distance learning delivery or online teaching and learning. I am only an email, phone call, or Zoom meeting / Google Hangout away: sboyerda@nmu.edu or (906) 227-1805. I will deliver one-on-one training sessions to full department offerings and anything in between. PLEASE reach out to me if I can be of any help whatsoever.

Please be watching your email in the coming days and weeks for more distance delivery resources and professional training sessions from the Center for Teaching and Learning and the Global Campus.

Stay healthy, safe, and SISU strong my faculty friends.

Best regards,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar

Read Vol. 1, Issue 39

*************************************************************************************************************

The Global Campus has adopted the Seven Principles to serve as the framework for online course delivery standards (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). The Quality Matters (QM®) peer-reviewed quality assurance program has been adopted to evaluate course design rigor. Both methodologies align with and parallel the call for learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interactions to promote active learning engagement (QM 5.2). For HLC accreditation purposes, all online courses must include learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interaction (regular and substantive, initiated by the instructor) because correspondence courses are not permitted.

For more information on the Global Campus online course requirements or the SoTL related to them, and/or to curate a conversation about high impact teaching design and delivery practices in your online courses, please reach out to Stacy, the Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar via email onlreview@nmu.edu or telephone (906) 227-1805.

Faculty are encouraged to contribute to the ONLINE BYTE OF THE WEEK. Please email Stacy at sboyerda@nmu.edu with your ideas.

REFERENCES

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3-7.

Standards from the Quality Matters (QM) Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. Retrievedfromhttps://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Vol. 1, Issue 37, April 6, 2020

This week’s BYTE serves up a smorgasbord of SoTL-informed hacks for successful distance delivery.

- There is no such thing as over-communication with your students. Communicate using a variety of methods: email, announcements, discussions, chat, Zoom, VoiceThread. Be clear and concise with your communications. While less is more, (fewer words with greater meaning), craft communications with sufficient detail to anticipate and answer student questions before they are posed.

- Construct learning activities and assignment instructions from the perspective that students may not know what is expected of them or how to use related technologies.

- Verify that PowerPoint slides or other documents used during lectures (synchronous or otherwise) are viewable on smaller devices such as smart phones; many students are using their cell phones to log into class.

- Consider the use of Zoom breakout rooms and live group chats to encourage learner-learner interaction.

- Keep the length of video recordings between 5-15 minutes to maximize student engagement.

- Identify students who are struggling with distance delivery and offer tailored guidance and support.

- To better accommodate student needs, record and share your live lectures.

- Use Slido, Kahoot!, or iClicker polls during synchronous class periods to offer opportunities for student participation.

- Be prompt in providing feedback to help students more rapidly connect the gaps between learning objectives (what you expect them to be able to do or learn) and their current performance.

- If using Zoom conferencing for lectures, call on students just as you would in class. Students can either use the chat feature or audio and video to respond.

- Invite guest speakers into your Zoom class. Guests who have been unavailable to participate prior to the COVID stay-at-home orders, may now have room on their calendars.

- Publishers are now providing students with free access to many textbooks and other resources. For instance, Cambridge University Press is offering free HTML access during the COVID-19 outbreak to over 700 titles. Cengage is providing free access to all of its digital learning platforms and ebooks.

As faculty family, let’s continue to weather this COVID-19 storm - together. Please know that I am always here, as are the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) instructional designers, and the Teaching and Learning Scholar, Lisa Flood, to support our faculty at large with distance learning delivery or online teaching and learning. I am only an email, phone call, or Zoom meeting / Google Hangout away: sboyerda@nmu.edu or (906) 227-1805. I will deliver one-on-one training sessions to full department offerings and anything in between. PLEASE reach out to me if I can be of any help whatsoever.

Please be watching your email in the coming days and weeks for more distance delivery resources and professional training sessions from the Center for Teaching and Learning and the Global Campus.

Stay healthy, safe, and SISU strong my faculty friends.

Best regards,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar

Read Vol. 1, Issue 38

*************************************************************************************************************