Greetings NMU faculty and welcome to the ONLINE BYTE OF THE WEEK, a newsletter created to share current scholarship of teaching and learning related to the virtual learning space, online teaching best practices, EduCat learning management system (LMS) tips and techniques, and to spotlight the exceptional means by which we bring cyber learning to life for our students.

Vol. 2, Issue 29, May 4, 2021

This week, I take my last BYTE as your ELCE Scholar. I write this final newsletter in disbelief for my incredibly rewarding two-year role has ended nearly as quickly as it began. Issue 29, our 76th since June 2019, is a walk down memory lane for me, a time for me to reflect and share with you what I have learned and accomplished along the way; although, much more work is to be done! This journey was only possible with the guidance and support of so many that I must thank.

First, I offer a very special thank you to Drs. Christi Edge and Liz Monske. They spent the summer of 2019 with me to onboard, share online teaching pedagogy, and norm the Global Campus online course design review process that they, along with the Center for Teaching and Learning and the Global Campus, constructed with both research and high impact teaching practices serving as the mortar.

Next, a round of applause with standing ovation for the Center for Teaching and Learning: Dean Leslie Warren, Matt Smock, Tom Gillespie, Stacey DeLoose, and Scott Smith and the Teaching and Learning Scholar, Lisa Flood. Our instructional design experts are an invaluable and indispensable resource to the faculty and university as a whole, an investment that yields significant professional development and online course quality dividends, not to mention that they host the best food fests on campus (just ask Scott about the hot dog roller and the Thanksgiving luncheon, Matt about Festivus and the feats of strength that I did not win, and Leslie about pie day, which, as I write this newsletter, is today). They immediately welcomed me as a member of their work team. We planned and presented at faculty workshops and the Upper Peninsula Teaching and Learning Conferences (UPTLC). We created an online course full of faculty teaching examples; Lisa was instrumental with this collaboration. Together, we served the faculty during one of the most challenging times in the history of academia, the pandemic, pivoting to online learning in the matter of only a few days’ time. From the Ally implementation to bi-weekly IDT and HLC accreditation meetings, Online Teaching Fellows, distance qualification courses, faculty and discipline consultations, I was honored to be a part of this outstanding professional group.

Mindy Nannestad is the north star of the Global Campus; her extensive planning, organizing, and analytical skills along with her attention to detail are out of this world. Thank you, Mindy, for everything.

Brad Hamel, Carley Harrington, and Dan Freeborn are the heart and soul of the Global Campus. They eat, breathe, and sleep online learning and access to education for all students by means of the internet. Rigorous learning can take place in an e-environment, synchronously or asynchronously, to meet the demands of those students who demand or prefer virtual programs. Brad, Carley, and Dan are, truly, the student (and faculty) accessibility champions of the university.

Steve VandenAvond is the true visionary for online learning at NMU. He leads the charge to provide educational access to the world. The funding from the distance education fee is reinvested into innovative online programs, not to replace those on the ground, as a means by which to expand our menu of course offerings and, perhaps, more importantly, provide educational access to those who otherwise would not be afforded with the opportunity to attend college.

To Joe Lubig, Adam Prus, Paul Mann, and the School of Education faculty (Derek Anderson, Christi Edge, Bethney Bergh, Abby Standerford, Mitch Klett, Judy Puncochar, Michelle Gill), thank you for piloting the next phase of the Global Campus online course design review process: a review of online courses using the Minimum Standards rubric.

Thank you to the guest contributors of the Online BYTE and to the faculty who offered suggestions via email and through conversations.

Most of all, to the Northern Michigan University faculty, I sincerely appreciate the complete honor and privilege to have learned from all of you over the last two years, having voraciously consumed your exceptional course syllabi, over 600 of them, and teaching best practices throughout my time with you. Thank you for your questions, feedback, patience, and recommendations throughout my time with you.

To the College of Business faculty, in particular, and Dean Carol Johnson, thank you for providing me with your support to perform this important work over the last two years.

I feel most accomplished for the faculty friends that I have made and the relationships I have forged. Knowing that my work has made an impact with respect to the quality of our online courses fills me with a great sense of pride. We received a clean bill of health from the Higher Learning Commission earlier this year, a direct outcome from the efforts of the faculty to demonstrate their online course design and delivery excellence, facilitated through the Global Campus online course design process. However, we must continue what we started and promised to our accreditors and ourselves and advance our online course design quality to the gold standard.

Along with the Teaching and Learning Advisory Council (TLAC), we developed an online course design and delivery peer observation process, (request one here), and created a glossary of pedagogic vocabulary, based on Quality Matters. As far as research is concerned, I attended one national and two regional conferences, presented at national and regional conferences and workshops for NMU faculty and administrators. Along with Steve, I co-created a structured process for online students to request a faculty evaluation of their prior learning for academic credit. I immersed myself in SoTL and produced peer-reviewed research. I authored one article and co-authored another in the pedagogic research space (shameless plug here).

Boyer-Davis, S. (2020). Technostress in higher education: A quantitative examination of the faculty perceived differences before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business and Accounting, 13(1), 42-58.

Stark, G., Boyer-Davis, S., & Knott, M. (2020). Extra credit and perceived student academic stress. Journal of Business and Educational Leadership, 10(1), 88-108.

This year, I served as the keynote speaker of a national conference, presenting the 2020 paper above. I will be presenting on this topic at another national conference in June.

Boyer-Davis, S. (2021, March). Hidden symptoms of the COVID-19 virus: Technostress in higher education. American Society of Business and Behavioral Sciences (ASBBS) National Conference, Virtual.

I have another co-authored SoTL article in review.

Berry, K., Boyer-Davis, S., Keiper, M., & Richey, J. (in review). The relationship between the ethical behavior of peers and grit: Evidence from university business classes. Journal of Business and Behavioral Sciences.

Christi Edge, Liz Monske, Brad Hamel, Steve VandenAvond, Matt Smock, and I have been invited to submit a peer-reviewed journal article:

Edge, C., Monske, E., Boyer-Davis, S., Hamel, B., VandenAvond, S., & Smock, M. (unpublished, proposal accepted December 2020). Generating and enacting a rigorous multi-step vision for organizational change: A case study of implementing university standards for distance education. The American Journal of Distance Education.

Some of my peer-reviewed SoTL presentations (individual and co-collaborative) during the ELCE Scholar position include:

Stark, G., & Boyer-Davis, S. (2020, June). Teaching critical thinking. Paper presentation at the Management & Organizational Behavior Teaching Society (MOBTS) National Conference, Fort Wayne, IN (virtual).

Knott M., Boyer-Davis, S., & Stark, G. (2020, June). The mental health crisis on college campuses: Classroom strategies to support student academic wellbeing. Paper presentation at the Management & Organizational Behavior Teaching Society (MOBTS) National Conference, Fort Wayne, IN (virtual).

Stark, G., & Boyer-Davis, S. (2019, June). Thinking about critical thinking. Paper presentation at the Management & Organizational Behavior Teaching Society (MOBTS) National Conference, Mahwah, NJ.

Boyer-Davis, S. (2019, May). Strategies to improve online administered student evaluation of teaching (SET) response rates. Paper presentation and demonstration at the Upper Peninsula Teaching and Learning Conference (UPTLC), Houghton, MI.

My summer work for the Global Campus will be spent wrapping up existing projects and onboarding the new member(s) of the team. Steve will be announcing who the new scholar (or scholars) will be; stay tuned!

I bid you all adieu, at least in this capacity.

Best regards,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar (2019-2021)

Vol. 2, Issue 28, April 16, 2021

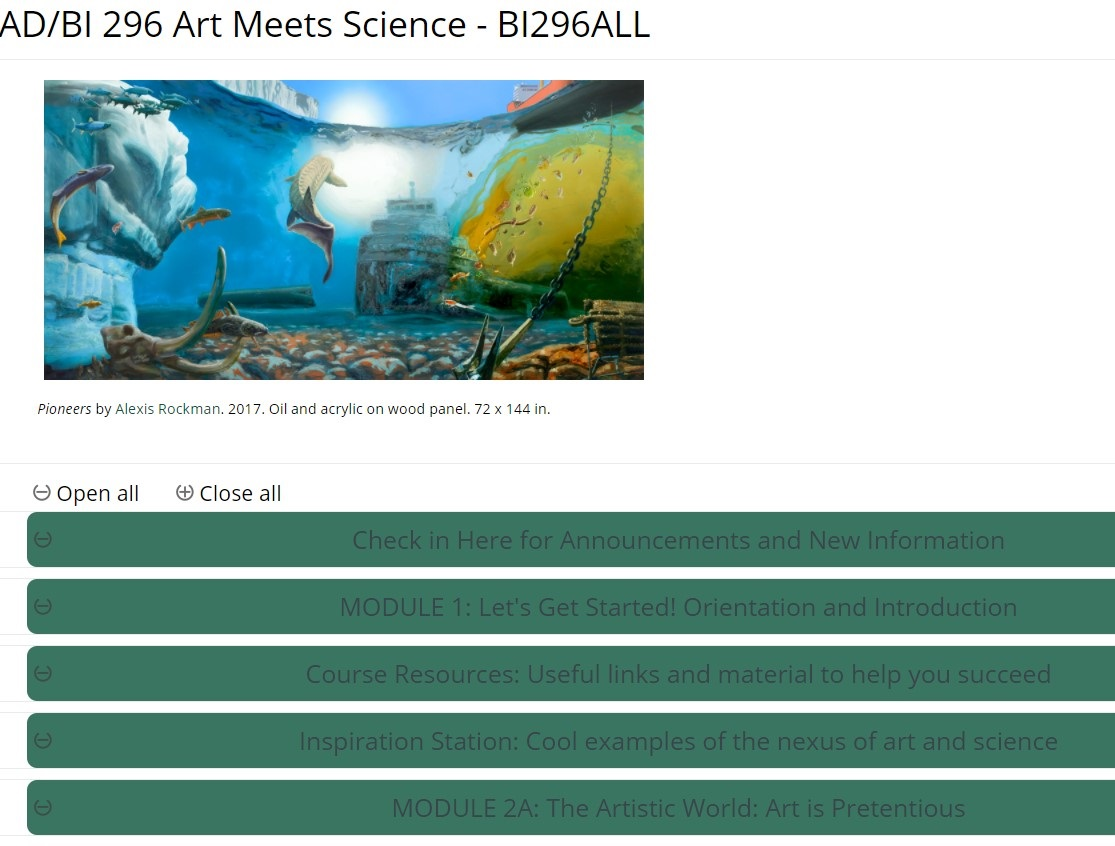

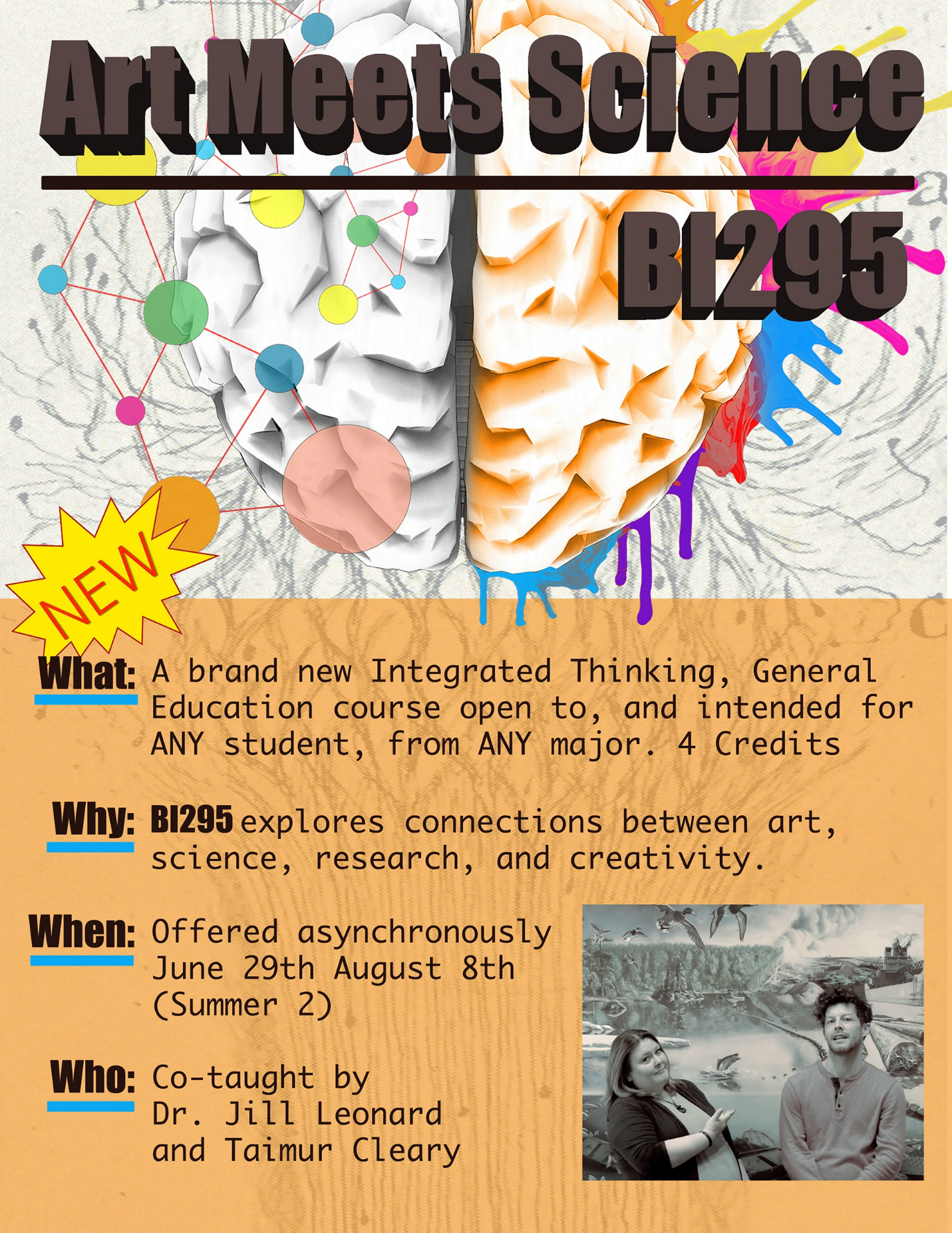

This week, the BYTE invited Professors Jill Leonard and Taimur Cleary to share with our readership more about their interdisciplinary online course creation: Art Meets Science. Enjoy this special edition of the Online BYTE of the Week!

Art Meets Science: A Collaborative Online Course from Scratch

By Jill Leonard (Biology) and Taimur Cleary (Art & Design)

We are lucky enough to be offering a new asynchronous online course this summer that is the byproduct of a longer collaboration between the two of us and our departments. While we cannot yet report on how the course is being received by students, we were asked to talk about how we went about constructing our course since it is a somewhat unusual co-taught model. Welcome to INTT222 Art Meets Science!

The course itself is an outgrowth of a longer collaboration centered around The Great Lakes Cycle, a series of paintings done by artist Alexis Rockman. As we worked together on that project, we became increasingly engaged by the interaction and interplay between art and science… and so we eventually decided that we wanted to offer a course on this topic to NMU students. From its inception, the course was never going to be tightly tied to the Rockman paintings, but rather move into a broader world of interactions between art and science…and the value of integration between disciplines in general. It’s also important to remember that this content area is outside both of our usual areas of emphasis… and so we knew it would be a lot of work to pull everything together.

Our first step was to brainstorm how we wanted to handle this amorphous topic and make it accessible to students. On the one hand, that involved a traditional outlining of content to be covered, and importantly a division of labor between the two of us for who would have responsibility for the various pieces. It also meant thinking hard about who we wanted the audience to be and how we needed to offer the course (logistics!) It also meant ensuring that both our departments and our Dean were supportive of the project.

It soon became obvious that for us to offer this as a co-taught course, we would need to do it in the summer since our teaching loads for the regular semesters are packed already. We also knew that we would have access to a larger pool of students if we went online with it. But, at that time (pre-COVID) we were both very green on teaching online. So, we were privileged to be accepted into the Summer 2020 version of the Online Teaching Fellows I program. It provided the perfect vehicle for us since we could work on our new course at the same time that we were learning best practices in online teaching.

Because we were truly starting from scratch, rather than converting an existing course or transforming a course that was based on a text or existing curriculum, we had enormous latitude… but that was also very daunting! To deal with this, we went to the basics and started with our learning objectives (outcomes) that we wanted for the course and those would be drawn in from the General Education program, since we knew we wanted this course to be included in Gen Ed. We were able to directly model our major assignments on the outcomes needed for General Education (Integrated Thinking), with the goal of making assessment easy in the long run. In addition, because we were starting from scratch, we placed Quality Matters best practices such as student interaction devices, student-instructor interactions, accessibility, etc., right into the initial outline so that they would be included naturally and not forgotten or forced.

Between the broad outline of the content we wanted to explore and the outcomes and best practices we wanted to include, we fairly quickly had an outline for the course. We then considered more holistic elements that we felt important, like making sure the course was as visual as possible to draw in artistic elements and to emphasize both creativity and data-driven research and practices. We wanted these to be concepts that the students did not just read about, but also experienced as part of the course design.

Obviously, all this development prior to actually starting to make the course “real” was time-consuming, but it was also exciting and fun! Development of a course like this, while certainly work, should be rewarding for the instructors and remind us all why we joined academia. Having the time to do this was a luxury afforded by the Teaching Fellows program. Having a good partner to work on it with, however, was the most important piece of the puzzle. We know that co-teaching has not been common at NMU, but we want to encourage you to explore it as a possibility. Having a partner in crime makes the whole process more enjoyable!

Once we had our course structure in place, then it was a matter of seeking out and coming up with appropriate content. In some cases, there were materials available to us on the web, in other cases we made our own videos or other materials (we try to mix up content type to increase engagement). And of course, we had to make EduCat cooperate with us (with lots of help from the CTL!) as we constructed the assignments and other materials that the students would work through. Again, a lot of work, but so much more reasonable once we had a clear vision of what we needed to accomplish.

So, did it work? Well, we came up with something that looks good to us. This summer we will offer it for the first time. And as of this writing, there are 26 students willing to take the leap with us! We’ll get back to you with a report on if we were really successful once the students engage with it!

*************************************************************************************************************

Please keep those BYTE newsletter ideas coming! We welcome guest contributors. Please consider answering our call to showcase the outstanding ways that YOU are teaching in the online, hybrid, hyflex, or in-person learning environments.

Stay healthy and safe,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar

*************************************************************************************************************

The Global Campus has adopted the Seven Principles to serve as the framework for online course delivery standards (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). The Quality Matters (QM®) peer-reviewed quality assurance program has been adopted to evaluate course design rigor. Both methodologies align with and parallel the call for learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interactions to promote active learning engagement (QM 5.2). For HLC accreditation purposes, all online courses must include learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interaction (regular and substantive, initiated by the instructor) because correspondence courses are not permitted.

For more information on the Global Campus online course requirements or the SoTL related to them, and/or to curate a conversation about high impact teaching design and delivery practices in your online courses, please reach out to Stacy, the Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar via email onlreview@nmu.edu or telephone (906) 227-1805.

REFERENCES

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3-7.

Standards from the Quality Matters (QM) Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. https://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Vol. 2, Issue 27, April 5, 2021

This week, the BYTE is all business as Drs. Jes Thompson, Gary Stark, Jim Marquardson, Ahmed Elnoshokaty, Murong Miao, and Professor Jodi Hunter offer their learner-learner pedagogic pearls of wisdom.

MGT 344 Managerial Communications, Dr. Jes Thompson

Introductions via Padlet (ex: https://padlet.com/jessitho/rda3x2gfrl4soaw2), I embedded the padlet code into the EduCat page and students had a "25 word challenge: Introduce yourself with one photo and 25 words, or less." The padlet page was a dynamic shared document that fostered learner-learner interaction and engagement at the beginning of the course.

Weekly Discussion Groups - I assign students into 7-person groups for the semester, each week they take turns leading the discussion thread for an assigned prompt.

Because of the group size, students build a "micro-community." This is great in a larger online class. The students get to know their group really well and move past generic responses and surface-level conversation because they practice relationship-building and authenticity with a smaller group.

Weekly Discussion Forums

Points Possible: 70 points; 10 points each

Due Date: Every Friday by 9 a.m.

Overview: Students will be part of one small discussion team (7 members) for the entire semester. Each week I will give a prompt, case study, scenario or specific question to discuss using the class forum function. Each week one student will be designated the discussion “leader” and must create the first post by midnight on Tuesday. All students will earn five points for writing and sharing their initial, coherent and concise (100-150 words) post responding to the prompt, and five additional points for replying thoughtfully (about 50-100 words) to at least two peers’ posts during the week.

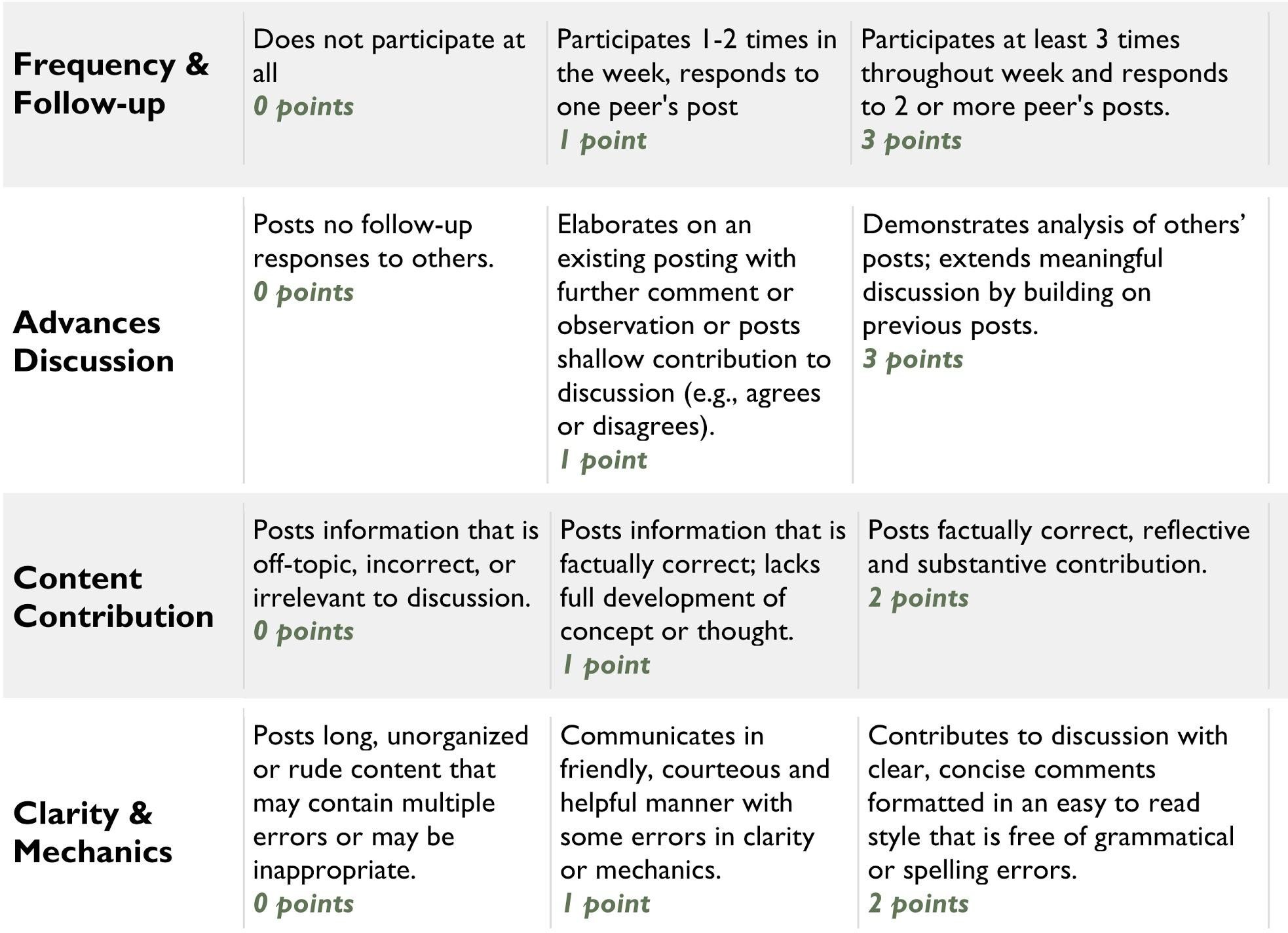

Rubric: Asynchronous discussion enhances learning as you share your ideas, perspectives, and experiences with the class. You develop and refine your thoughts through the writing process, plus broaden your classmates’ understanding of the course content. I will use the following rubric to assess the quality of your discussion contributions.

MGT 343 Human Resource Management, Dr. Gary Stark

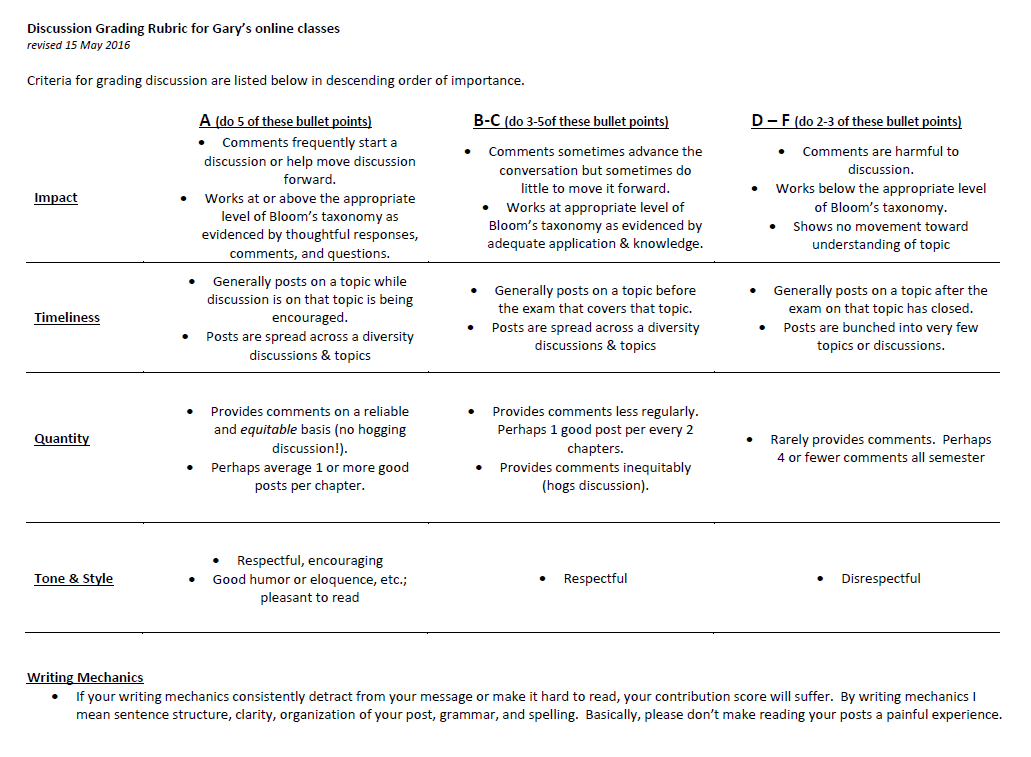

I don't do anything particularly fancy. My online classes have all been asynchronous (MGT 343 during the summer). I post discussion questions using the "Forum" tool in Moodle. Typically, we have fairly good discussion, but it takes some work getting them to respond to each other. They'd often rather wait for me to weigh in. I set each of those discussions so that every post is automatically emailed to the students. That way they can keep tabs on discussion with almost no effort on their part. Clearly, that can be overwhelming for them but I instruct them how to create folders and automatic sorting. I don't directly require a certain number of responses per chapter or post. Students are graded more on their overall contribution across the semester. Please see the rubric I use, below.

It's never as much discussion as I want, but it is summer (hard for students to be engaged when the weather is perfect) and the technology is quite simple and the discussions are easy to follow.

CIS 222 Quantitative Business Problem Solving, Dr. Jim Marquardson

I've found that simple forums are an effective way to have students engage with each other. I typically require students to post a response to a prompt and reply to one of their peers. The forum type I prefer is a "Q and A Forum" in which students cannot see any posts until they have responded to the question I posed. One downside is that students cannot see or respond to their peers' posts for up to an hour after they have submitted their own posts. This delay is unavoidable in Moodle--there is basically a job that runs periodically to determine if a student has made a post, yet, thereby unlocking the view of their peers' posts.

The Center for Teaching and Learning has recommended using multiple due dates for this type of forum. The student's post responding to the instructor's question could be due on a Wednesday, and the student's reply to a peer might be due on a Friday, for example. In my CIS 222 Quantitative Business Problem Solving class, I give students a semester case in which they have to use Excel spreadsheets to solve a business problem of their choosing. I've found that students struggle to think of ideas for their project, so I created a required forum post early in the semester that asks students to propose a topic for their business case and describe the features they will implement. To encourage learner-to-learner interaction, I require students to respond to a peer and suggest an additional spreadsheet feature that could be useful. The forum helps students commit to a project early on in the semester and they also get ideas for improving their project.

CIS 222 Quantitative Business Problem Solving, Dr. Ahmed Elnoshokaty

For my asynchronous classes, I did the following learning activities:

- Like Jim, the Q and A forum following the same multiple-dates deadline setting which has been engaging students in the asynchronous class.

- I used for course project presentations and peer discussion Voicethread, I guess it added more peer interaction.

- I added forums for assignments that are a little bit challenging, where I expect students to work together to muddle through.

For, synchronous online classes, I did the following learning activities (I try to keep each learning activity no longer than 20 minutes and then switch to another and have the class more engaging to students)

- Flipped classroom: listening to a podcast or read an applied research article before introducing some topics (gets students more motivated)

- Zoom breakout rooms for in-class hands-on group assignments

- MCQ formative assessments through Kahoot! interactive quiz (I view results and address misconceptions directly after quiz)

MKT 230 Introduction to Marketing, Dr. Murong Miao

Marketing Group Project Instructions

Project Overview

In the project, your group will play the role of a small business’s marketing team to develop a comprehensive marketing plan for the business. Your group will prepare a formal marketing plan as well as make two presentations of your ideas in the middle and at the end of the semester.

What You Need to Do

Your job in this project is to develop a complete marketing plan for your chosen business. First you need to collect information about the product/company and its consumers. This research will enable you to do a situational analysis of the company and to define your overall marketing objectives and strategies. Make sure you try to find out as much as you can about the company and its industry and thoroughly understand the company’s situation before you create your main marketing ideas.

Based on the information you collected, you should define the marketing objectives you want to achieve through your plan and quantify these objectives so that the effectiveness of the plan can be measured if it is carried out. When you design your objectives, keep in mind that marketing is an integral part of business decisions. So, your objectives should fit well into the company’s overall mission and business plan.

Next you need to identify the appropriate target market(s) for the business and design the marketing mix that will help you achieve your marketing objectives. This includes all four components of the marketing mix: product, price, promotion, and place/distribution. When defining target markets, please be as specific as possible in terms of the intended target markets’ demographics, socioeconomic status, psychographics, and other identifying characteristics. Be sure to justify why you think these target markets are appropriate. For the marketing mix components, please give as much detail about each component as possible.

For the final components of the marketing plan, you will identify the implementation and logistic details for your plan such as the necessary organization structure to support the marketing plan, and the implementation steps and timeline. In the end, you also need to decide how you will monitor the campaign’s performance, how you will evaluate the performance, and any alternative courses of action if your campaign does not work out as expected.

Group Project Grade

Your group’s final project grade will be affected by the quality of each section you submit during the semester.

Final Group Project: (1) Paper- 150 points & (2) Two Presentation- 100 points

Two Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Wait until almost the end of the semester to start the project. Some students tend to delay their group project until the last minute. This can usually have a very negative effect on the quality of the project. You should start the project as early as possible to make sure you don’t run into problems when you are almost running out of time. If you would like to start the project early and other group members are not cooperating, be persistent. Shall your persistent effort fail, you should notify the professor as soon as possible.

- Divide and conquer without regard to what other group members are doing in other parts of the project. A good marketing plan should be one that is well-integrated. Many students approach group projects by dividing the work and then each one working on his or her own. While this approach is OK, students who are given a later part of the marketing plan should know what group members working on earlier parts are doing or have done. For example, the marketing mix strategies should reflect the chosen target audience and brand positioning in earlier sections of the plan. Students working on earlier parts of the marketing plan should start early on in the project and should actively pass on their information and analysis to other group members. A marketing plan consisting of fragmented, totally-unrelated sections (both in terms of content and writing/transition) will not receive good evaluation.

Presentation:

Power-points slides need to be submitted to EduCat Dropbox.

Each group will present its marketing plan both in the middle and at the end of the semester. The presentation will be 15~20 minutes long. It is each group’s responsibility to make sure all materials are presented within the given time frame. A common mistake that you should try to avoid is to spend too much time on describing the situation and not enough time on your actual “big idea”. Keep in mind that your presentation will be graded based on what the audience see and hear in the given timeframe, not on what you may have prepared on slides. Logistic-wise, the group can choose which members will do the presentation. The grade will be based on the clarity and organization of your presentation as well as the use of basic presentation skills, such as maintaining proper eye contact, not reading from prepared speech, etc.

Final Group Paper rubric:

|

Content |

Points Assigned |

|

Executive summary: A short and concise synopsis of your marketing plan. |

10 |

|

Company/Industry Analysis |

10 |

|

Situational Analysis *Provide a SWOT matrix with at least two factors in each cell and a short explanation of each factor *Provide a summary to discuss how you plan to convert weaknesses into strengths, convert threats into opportunities, and match internal strengths with external opportunities to develop competitive advantages. |

20 |

|

Marketing objectives *Set objective(s) of your marketing activities *Define your potential market *Select at least one segmentation variable to segment your potential market and justify why you consider the selected segmentation variable(s) as appropriate. *Based on your selection of the segmentation variable(s), identify and explain different market segments of your product. |

10 |

|

Target market and positioning: Target market *Evaluate different market segments that you identify through the market segmentation activity (discussed in the previous section). *Select your target segment(s) and explain why. Positioning

Visually present the positioning by drawing a perceptual map. |

15 |

|

Marketing Strategy: |

|

|

Marketing mix strategy – Product planning *Explain the type of consumer product that your company is offering and the purchase behavior of consumers associated with the consumer product type. * Develop brand personality of your product brand (Please provide detailed explanation to support your arguments) *Describe the stage of the product life cycle that your product is in and set objectives of price, promotion and place activities accordingly. |

15 |

|

Marketing mix strategy – Promotion planning *Identify the theme of messages that you are trying to communicate through your promotion planning activities. *Advertising: type of product advertisement (explain why this type of product advertisement can help you reach your advertising objective), media (Select an appropriate type of advertising media that you plan to use to advertise you product and explain why it was selected), and advertising schedule (explain why a specific scheduling approach is selected). *Sales promotions: objectives, the types of sales promotions used to reach the objectives *Other promotional methods (Optional): personal selling & public relations |

15 |

|

Marketing mix strategy – Price planning *Estimate the annual total fixed cost, unit variable cost of producing and marketing your group product as well as the anticipated annual quantity of product sold *Use a cost-oriented approach or a profit oriented approach to determine the price level of your group product *Calculate break-even point *Select a pricing strategy to set your list price and provide explanation to support your arguments. |

15 |

|

Marketing mix strategy – Place/Distribution planning *Choose a marketing channel (e.g., indirect channel to have one retailer) that you plan to use to distribute your product. *Use the channel selection factors (i.e., customer characteristics, product attributes, type of organization, competition, environmental forces, and characteristics of intermediaries) to specifically explain why your selection of marketing channel is appropriate. *Identify the target market coverage approach (i.e., intensive distribution, selective distribution or exclusive distribution) that you plan to adopt to distribute your product and explain why. |

15 |

|

* Evaluation and Control: If your plan is to be carried out, how will its success be evaluated? What types of information will need to be collected in order to assess performance? What adjustments do you need to make if the plan does not work out? |

15 |

|

* Appendices: Include any appendix you feel that may enhance or add interest to your marketing plan. This could include, for example, images of product packaging or sample marketing materials that you have designed. *Proofreading to ensure the cohesiveness of the paper & make sure to follow the format requirements (Times New Roman; 12-point font; double space; paragraph format) *Note. Please indicate the work responsibilities of members in the work assignment table and attach the table in the last page of the paper. For the name(s) missing in the table, the member (s) will receive a “0” for the group assignment. Only one person per-group needs to submit/ upload the assignment paper on EduCat dropbox titled “Final Group Project”. |

10 |

The Marketing Plan Template

At the end of the semester, your group will need to hand in a complete marketing plan. The plan should be on double-spaced, typed papers. It should follow an essay format with proper use of section headings. Oftentimes students ask whether their paper should be in essay format or bullet point format. The plan should be written in an essay format. Your report will be graded on its quality of information, its strategic relevance and practicality, its creativeness, and its clarity of organization and writing. The report should be no less than 15 pages. But it should follow the template below:

- Title page: This should include the full title of your project, your names, the course number and name, your section time, the professor’s name, and the due date.

- Executive summary: Write this section when you have completed your Marketing Plan but place it 1st in order (right after your title page). This one-page managerial summary should give a busy “executive” an idea of your plan without having to read your entire report. Be sure to include a brief description of your product benefits, target market, customer needs, value proposition, performance expectations, and the keys to success.

- Company/Industry Analysis: An overview of the company, including its business, its history, etc., and the industry that it operates in. It should cover the following components:

- Company Mission

- Company’s Strategic Goals (financial and non-financial)

- Company’s Core Competency

- State of the Industry: what is the state of the industry today? How does the company fit into the industry?

- Situational Analysis: This section presents an in-depth look at the company’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats and as such should address relevant issues in the industry, the competition, its customers, the macro-environment and the company itself. You can distinguish strengths and weaknesses from opportunities and threats by asking this question. “Would this issue still exist if the company did not exist? If the answer is yes, the issue is an opportunity or threat.” This section will include the following sub-components:

- Market Needs, Trends, and Growth

- Competitive Landscape: How competitive is the marketplace? Who are the key competitors? How are they different from your company?

- SWOT Analysis, including strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. Identify at least three for each.

- Marketing objectives: What would you like to achieve through your marketing plan? These should be realistic and concrete objectives that can be measured against the actual performance were the plan to be carried out. There should be some quantified objectives.

- Target market and positioning: Who are your target customers? Describe them as best as you can in terms of demographics like gender, age, life cycle, income, education, occupation, race/ethnicity; geographics; psychographics such as their interests and activities; behavioral such as overall loyalty to the brand, first time or regular customers, etc. What is the rationale behind why they are the optimal target market segment? How do you want to position your brand? What are your main points of difference?

- Marketing Strategy:

- Product Strategy: describe your brand and product features and benefits (from the perspective of the target market); key factors that will determine your success with the product; and critical issues that will need to be addressed.

- Price Strategy: how will you set the price? Select price objective; determine demand and estimate costs; analyze a major competitor’s price; select a pricing method; finally select the final price.

- Place Strategy: Will you use push or pull strategy and why? Will you use retailers or wholesalers? Will you have a website? If so, will it be promotional or transactional?

- Promotion Strategy: establish promotion objectives, and choose a message and vehicles for communicating that message.

- Evaluation and Control: If your plan are to be carried out, how will its success be evaluated? What types of information will need to be collected in order to assess performance? What adjustments do you need to make if the plan does not work out?

- Appendices: Include any appendix you feel that may enhance or add interest to your marketing plan. This could include, for example, images of product packaging or sample marketing materials that you have designed.

MGT 121 Introduction to Business, Professor Jodi Hunter

Learning Activity: Shark Tank

Ready to be an entrepreneur? Your final project is to create a product or service and sell your idea to gain support from an investor (your professor), Shark Tank style!

Your company can offer a physical product or a service, but it should not just be a copy of something already offered … BE CREATIVE! Think outside of the box …

You will need to include the following in your project:

Part 1 (10 points): 1-2 page summary/outline about your company including:

- the company’s name and objectives

- the company’s mission

- the company’s basic details (company location, senior management’s names

and roles, when founded, logo and slogan, etc.)

- a brief description of the product or service

- how you came up with the idea for your product/service

- the top 3 problems your product/service are addressing

This component will be submitted at the end of Week Four, but will be graded as part of the final grade. I will provide feedback on this component that will help guide you on the final presentation component.

Part 2 (45 points): A 10-slide presentation on your entire project. The outline you should use is below. Your PowerPoint should be submitted with your video.

During your video, you will reference this slide show, so that the professor can follow along your PowerPoint while watching YOU on video present it. I will be watching these on two computer screens side by side, so you do not have to have the PowerPoint actually showing in your video, but you should be using it while you are making your video, as if you were doing this in person and the slide show was in the background for the viewer.

Part 3 (55 points): Video Presentation Requirements:

Your video must be UNDER 10 minutes, but at least 5 minutes. This essentially means you have to be concise and make sure that you are READY when you start. Videos over 10 minutes will automatically lose 20 points, no matter how great they are. Part of presentation is being concise and clear. You don’t need to share every single detail, focus on the most important items.

All students within their assigned teams must participate in the video. Each student will be graded SEPARATELY on your participation in the video component.

This project is worth 110 points: 10 points for the paper, 45 points for quality of your PowerPoint, and 55 points for your video presentation. Please refer to the rubric for specific details as to how you will be graded.

PowerPoint Presentation Requirements:

Slide #1: Cover Slide (include your company name OR logo & your name)

Slide #2: Company Name and Objectives (remember to use bullet notes)

Slide #3: Company Mission Statement (sentence(s) allowed for this slide)

Slide #4: Basic Details About Company (company location, senior management’s names and roles, when founded, logo and slogan, etc.)

Slide #5: The Marketing Mix: Product, Place, Price, Promotion (use bullet notes)

Slide #6: How You Came Up with the Idea for your product/service (use bullet notes)

Slide #7: Top 3 problems your product/service are addressing (use bullet notes)

Slide #8: A compelling message that states why your product/service is different than competitors (make sure you are specific – give details)

Slide #9: Conclusion Slide (quick overview of 4-5 main points of your project)

Slide #10: Complete the Sale with a powerful closing sales pitch that answers “Why is this product worth buying/investing in?” (this will make or break the Sharks investing in your project)

Remember to include pictures and other graphics, not just plain text on slides.

Grading Rubric for Shark Tank:

|

Grading Criteria |

Excellent 90-100% |

Good 75-89% |

Fair 50-74% |

Inadequate 0-49% |

Score for each |

|

Paper Outline (10 points) |

Summary generated excitement, provided an overview of the business, and outlined main points. |

Summary was brief, provided an overview of the business, and outlined main points. |

Summary was brief, provided an overview of the business, and outlined some main points. |

Summary was brief and provided only an overview of the business OR an outline of main points. |

|

|

Powerpoint Content (35 points) |

Powerpoint contained detailed information regarding all requested information. |

Powerpoint contained information regarding at least eight aspects of requested information, with some degree of detail. |

Powerpoint contained information regarding at least five aspects of requested information, with some degree of detail. |

Powerpoint contained information regarding less than five aspects of requested information, with little or no detail. |

|

|

Powerpoint Layout (10 points) |

Presentation was done in bullet point format, easy to follow, eye appealing, utilizing the instructions and had no spelling or grammatical errors. |

Presentation was done in bullet point format, easy to read, utilizing the instructions and had few spelling or grammatical errors. |

Presentation was done in paragraph format, and/or was not designed for ease of reading, and/or had many spelling or grammatical errors. |

Presentation wasn’t presented in proper format and/or had many spelling or grammatical errors. |

|

|

Video Presentation Content (35 points) |

Ideas were presented in concise, clear detail, all relevant points were discussed, and it was consistently obvious there was great thought behind it. |

Ideas were mostly presented in clear detail, and most relevant points were discussed, appeared to have significant thought behind it. |

Ideas were presented in some detail; some relevant points were discussed, with some thought behind it. |

Ideas were somewhat lacking in detail, few relevant points discussed, and seemed to lack much thought behind it. |

|

|

Video Presentation Professionalism (20 points) |

Video was presented professionally, was clearly well prepared, organized, met the time requirements. |

Video contained a good level of professionalism; some preparation was evident, fairly well organized, and met time requirements. |

Video could have been improved in terms of professionalism, little/some preparation was evident, organization could have improved, met time requirements. |

Video was not presented professionally, unorganized, or went over time requirements. |

|

|

Total score of 110 points possible total points |

|

||||

*************************************************************************************************************

Please keep those BYTE newsletter ideas coming! We welcome guest contributors. Please consider answering our call to showcase the outstanding ways that YOU are teaching in the online, hybrid, hyflex, or in-person learning environments.

Stay healthy and safe,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar

*************************************************************************************************************

The Global Campus has adopted the Seven Principles to serve as the framework for online course delivery standards (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). The Quality Matters (QM®) peer-reviewed quality assurance program has been adopted to evaluate course design rigor. Both methodologies align with and parallel the call for learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interactions to promote active learning engagement (QM 5.2). For HLC accreditation purposes, all online courses must include learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interaction (regular and substantive, initiated by the instructor) because correspondence courses are not permitted.

For more information on the Global Campus online course requirements or the SoTL related to them, and/or to curate a conversation about high impact teaching design and delivery practices in your online courses, please reach out to Stacy, the Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar via email onlreview@nmu.edu or telephone (906) 227-1805.

REFERENCES

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3-7.

Standards from the Quality Matters (QM) Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. https://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Vol. 2, Issue 26, March 29, 2021

Through the remainder of March and early April, the BYTE will highlight our expert faculty and their innovative pedagogy to promote learner-learner interaction in asynchronous courses. Next week, our BYTE is all business as Drs. Jes Thompson, Jim Marquardson, Ahmed Elnoshokaty and Professor Jodi Hunter offer their learner-learner pedagogic pearls of wisdom. This week, we present our second guest contributor, Dr. Vince Jeevar, Assistant Professor in the Psychology department. A special thank you to Vince for sharing his teaching techniques related to video discussion forums with the BYTE readership. Vince, take it away…

VIDEO DISCUSSION FORUMS

One of the biggest challenges I've found teaching online is bringing a sense of class connection, with both instructor to students, and student to student relationships having some challenges. One way I've found to help foster a connection is to include a video presentation component in classes, it helps for students and instructors to see each other as humans. In the online world, it's easy online to see people as wall of text, but when posting videos, it brings faces, or at the very least, voices (for those who are shy and choose to present using audio over a PowerPoint) into the classroom.

For each module, we'll have a video presentation where students will give feedback to each other. I set a minimum number of classmates (depending on the class size) to be responded to, and feedback needs to be at least 100 words. Having a word count means students can't get away with a 'nice presentation' comment and be done; they have to actually watch the videos and engage if they want to earn the grade.

When implementing this, through trial and error (mostly error), I discovered a best practice of allowing students to post their videos anywhere they like and posting just the link into an EduCat discussion forum in class. Most students choose to post on YouTube, but I do set up a WildCast Pod for each class as an option as well, and there are many other tools students could use. As long as the video is accessible, it doesn't matter where it's posted.

Of course, it's more work (for students and instructors) so there are some occasional grumbles, but I get far more students talking about how they appreciate the interaction and 'feel like they're in class' than those who grumble. If that changes at any point, I'll revisit my approach, but for now, videos seem to be a popular component. (Vince)

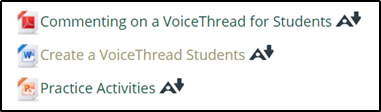

Please see below for web links for more information regarding video presentation software such as VoiceThread and Prezi and other multimedia tools such as Haiku Deck, FlipGrid, and Glogster (multimedia posters).

*************************************************************************************************************

Please keep those BYTE newsletter ideas coming! We welcome guest contributors. Please consider answering our call to showcase the outstanding ways that YOU are teaching in the online, hybrid, hyflex, or in-person learning environments.

Stay healthy and safe,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar

*************************************************************************************************************

The Global Campus has adopted the Seven Principles to serve as the framework for online course delivery standards (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). The Quality Matters (QM®) peer-reviewed quality assurance program has been adopted to evaluate course design rigor. Both methodologies align with and parallel the call for learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interactions to promote active learning engagement (QM 5.2). For HLC accreditation purposes, all online courses must include learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interaction (regular and substantive, initiated by the instructor) because correspondence courses are not permitted.

For more information on the Global Campus online course requirements or the SoTL related to them, and/or to curate a conversation about high impact teaching design and delivery practices in your online courses, please reach out to Stacy, the Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar via email onlreview@nmu.edu or telephone (906) 227-1805.

REFERENCES

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3-7.

Standards from the Quality Matters (QM) Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. https://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Vol. 2, Issue 25, March 16, 2021

Through the remainder of March, the BYTE will highlight our expert faculty and their innovative pedagogy to promote learner-learner interaction in asynchronous courses. Our first contributor is Dr. Amy E. Barnsley, Associate Professor in the Mathematics and Computer Science department. A special thank you to Amy for sharing her teaching techniques related to group quizzes in departmental math courses with the BYTE readership.

Group Quizzes in Developmental Math Classes, Amy Barnsley

Group quizzes are 5% of the overall grade for my MA090 Beginning Algebra and MA100 Intermediate Algebra classes. There are 8 group quizzes. I drop the lowest quiz score. This helps alleviate some of the stress when a group fails to meet for one of the quizzes.

In the introduction forum, students are asked to introduce themselves and are encouraged to exchange contact information.

Post a message or video about yourself. This is just a simple introduction which can include what your major is, what you hope to get out of college, some random fun fact about you, what you want to do when you grow up, or anything you want to share. Post a photo to practice uploading photos. You must also respond to at least one student. You will be required to do some group work in this class. You can have 2-3 people in a group, so now would be a good time to try to group up. Share contact information. You do not have to meet in person, but will have to work together on group quizzes.

I then create a “Who is in your group?” Survey in EduCat. I take that information and create a Google doc that has the names and email addresses of persons in each group. I post the Google doc in the EduCat course, but students can only view it; they cannot edit the Google doc. If students report they do not have a group, I form the group for them. As students drop the class or become non-responsive, I rearrange the groups and update the Google doc.

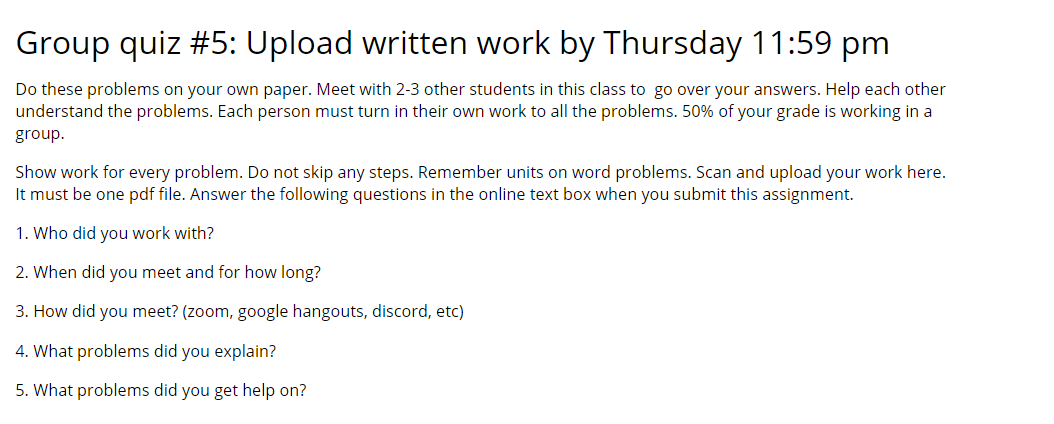

Group quizzes are worth 100 points. Half of the points are the math work, and half the points are given for answering the following questions:

I am pretty generous with the 50 group work points. I rarely give less than 50 if they made some attempt to meet. As I grade, I write down the names of the persons in the group members and I grade those one after another. I find that if they truly worked in a group, they tend to have the same errors. If someone has wildly different answers but said they worked in a group, I will leave a comment like this “Your answers do not match your group. Please leave enough time when you work with your group to really compare answers and work together to learn the material,” but I still give them 50 points. This is usually enough to prod them into genuinely working together the next time.

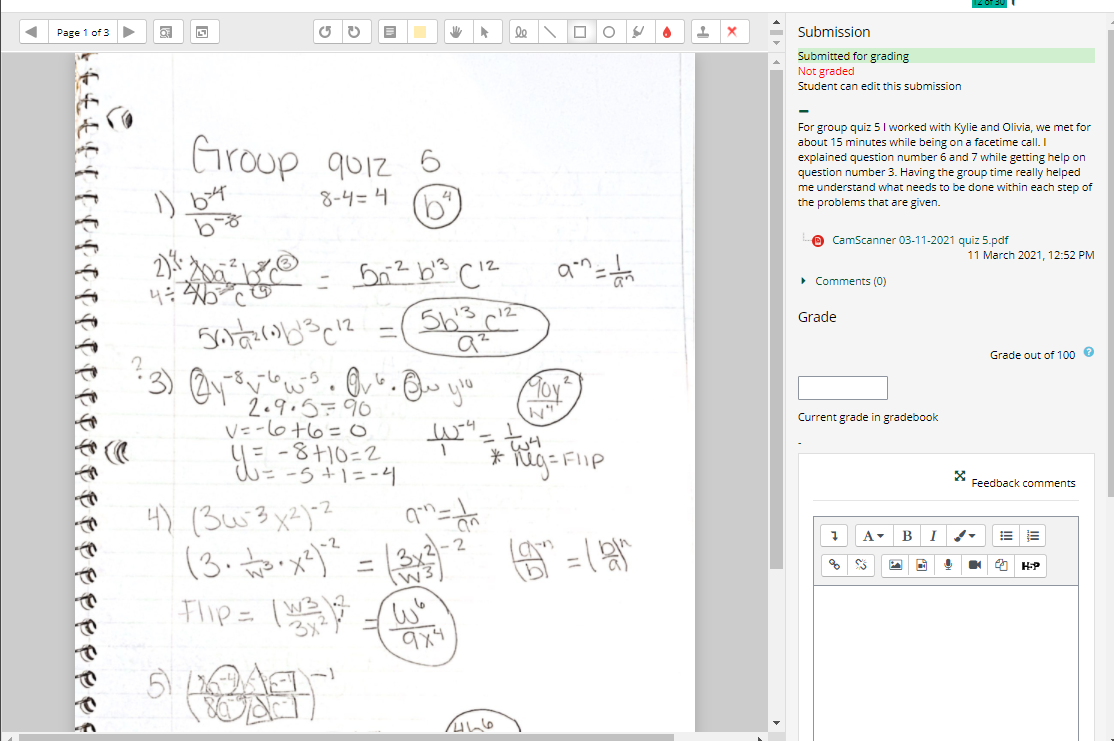

Here are three samples of the answers to the group work questions:

Sample 1: For group quiz 5 I worked with Axxx and Tyyy, we met for about 15 minutes while being on a FaceTime call. I explained question number 6 and 7 while getting help on question number 3. Having the group time really helped me understand what needs to be done within each step of the problems that are given.

Sample 2: My group is Jxxx and Myyy. We met on Thursday afternoon for about 20 minutes or so over FaceTime. We compared our answers and spent time discussing #3,4,6,7 I got help on #6 and explained #4. We collectively did the others together.

Sample 3:

1. Txxx and Myyy

2. We did meet on Friday afternoon for 1 hour.

3. Snapchat

4. Mostly, we went over the problems with graphs especially the absolute value.

5. I got help on question 10 regarding simplifying

6. Everybody in the group contributed.

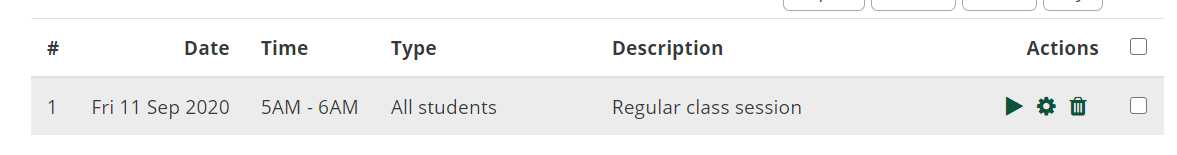

Here is a screenshot of what it looks like in EduCat:

*************************************************************************************************************

Please keep those BYTE newsletter ideas coming! We welcome guest contributors. Please consider answering our call to showcase the outstanding ways that YOU are teaching in the online, hybrid, hyflex, or in-person learning environments.

Stay healthy and safe,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar

*************************************************************************************************************

The Global Campus has adopted the Seven Principles to serve as the framework for online course delivery standards (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). The Quality Matters (QM®) peer-reviewed quality assurance program has been adopted to evaluate course design rigor. Both methodologies align with and parallel the call for learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interactions to promote active learning engagement (QM 5.2). For HLC accreditation purposes, all online courses must include learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interaction (regular and substantive, initiated by the instructor) because correspondence courses are not permitted.

For more information on the Global Campus online course requirements or the SoTL related to them, and/or to curate a conversation about high impact teaching design and delivery practices in your online courses, please reach out to Stacy, the Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar via email onlreview@nmu.edu or telephone (906) 227-1805.

REFERENCES

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3-7.

Standards from the Quality Matters (QM) Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. https://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Vol. 2, Issue 24, March 8, 2021

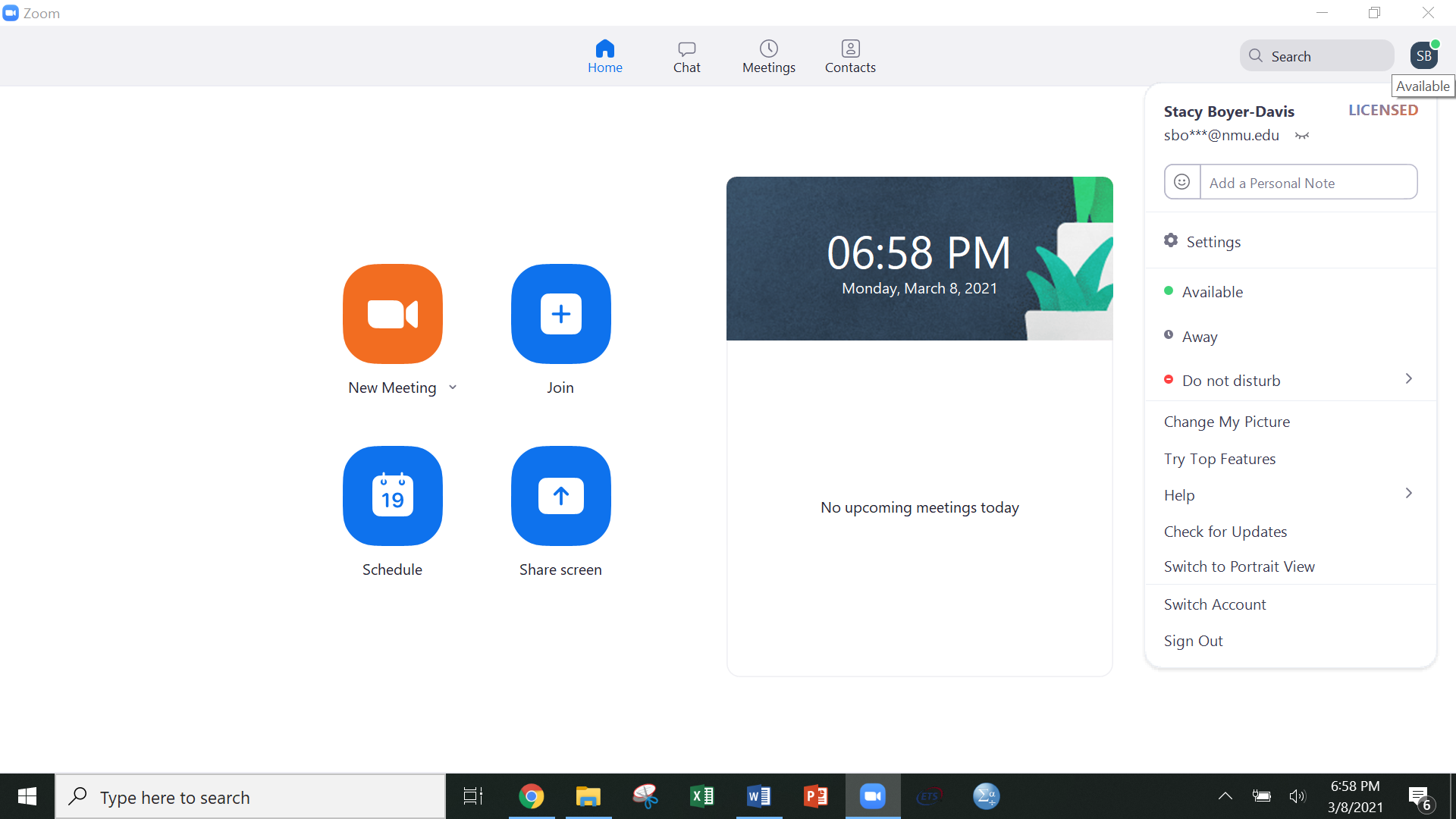

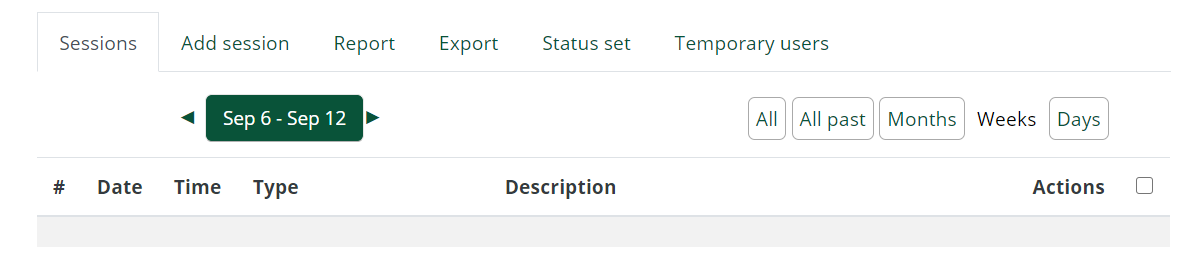

This week, let’s snack on Zoom, an application that has become incredibly important to teaching delivery in our pandemic environment and a way for us to stay connected with family, friends, and colleagues while physically distancing. On a regular basis, Zoom provides updates to launch program enhancements and patch any issues. To update Zoom (PC or Mac) to the newest version, open Zoom on your desktop. Click on your initials or photo image at the top right side of your screen. Please see “SB” below, for an example. A dropdown menu will appear. Then, select “Check for Updates” and run any that are offered. For iOS or Android, the Zoom mobile app will provide a notification that an update is ready when available.

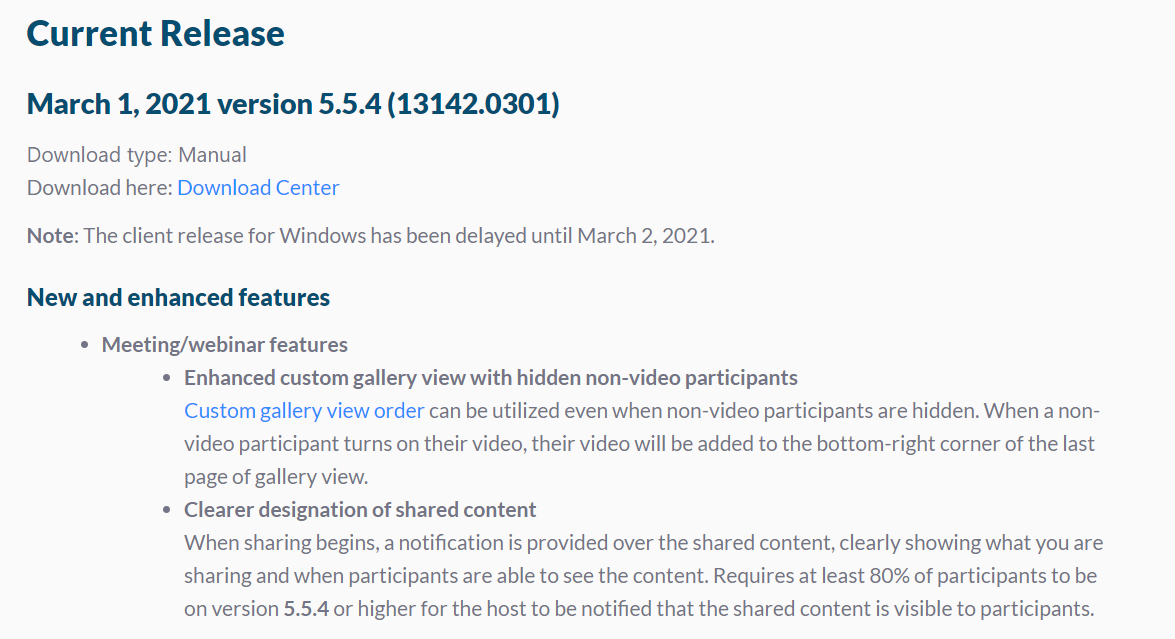

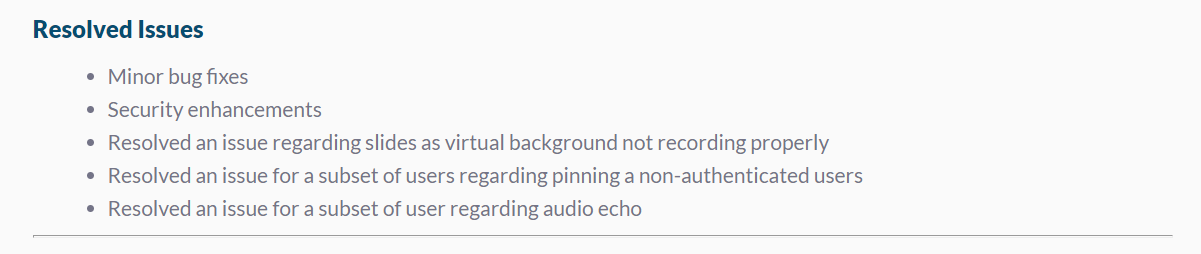

Please see below for information regarding the most recent Zoom update.

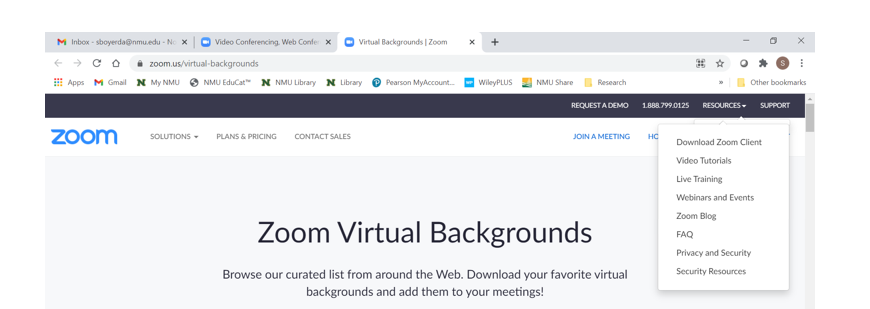

Zoom has a collection of backgrounds beyond those offered in the application. To browse the library of virtual Zoom backgrounds, click the link below.

For other Zoom how-to’s, please see the Resources menu and choices including video tutorials, live training, webinars and events, Zoom blog, and FAQ.

*************************************************************************************************************

Please keep those BYTE newsletter ideas coming! We welcome guest contributors. Please consider answering our call to showcase the outstanding ways that YOU are teaching in the online, hybrid, hyflex, or in-person learning environments.

Stay healthy and safe,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar

*************************************************************************************************************

The Global Campus has adopted the Seven Principles to serve as the framework for online course delivery standards (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). The Quality Matters (QM®) peer-reviewed quality assurance program has been adopted to evaluate course design rigor. Both methodologies align with and parallel the call for learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interactions to promote active learning engagement (QM 5.2). For HLC accreditation purposes, all online courses must include learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interaction (regular and substantive, initiated by the instructor) because correspondence courses are not permitted.

For more information on the Global Campus online course requirements or the SoTL related to them, and/or to curate a conversation about high impact teaching design and delivery practices in your online courses, please reach out to Stacy, the Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar via email onlreview@nmu.edu or telephone (906) 227-1805.

REFERENCES

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3-7.

Standards from the Quality Matters (QM) Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. https://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Vol. 2, Issue 23, February 26, 2021

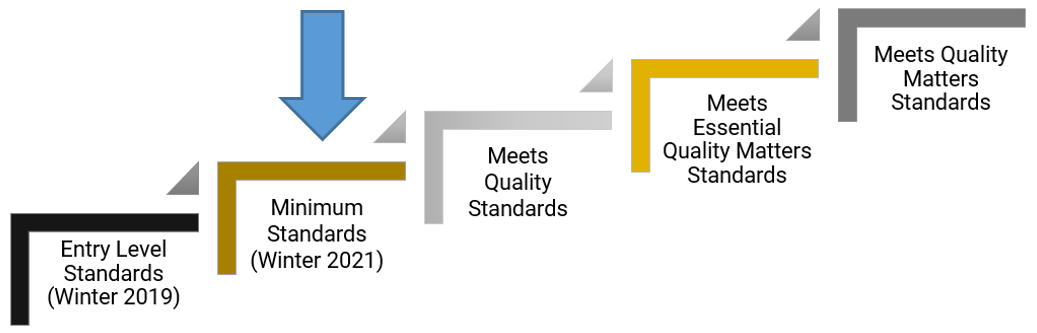

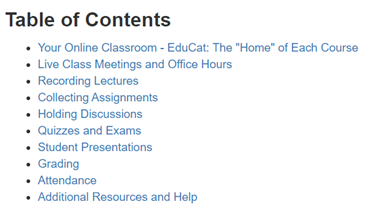

This week, the BYTE is pleased to announce that NMU has graduated to the next phase of the online course design review process: Minimum Standards. Effective Winter 2021, the ELCE faculty scholar began reviewing online courses along with syllabus copies. Over the last two years, we have been evaluating course syllabus copies using Entry Level Standards. To prepare faculty for the next phase of the review process, the faculty review team concurrently provided teaching faculty with constructive syllabus feedback through the lens of Minimum Standards when reviewing syllabus copies at Entry Level Standards. In the first step, Minimum Standards feedback was limited in scope to the syllabus only and not the online courses themselves.

Minimum Standards, “Bronze” (Online Course Design)

|

QM |

Design Area |

Description |

|

2.1 |

Course Learning Objectives |

The course learning objectives, outcomes, or course/program competencies are measurable. |

|

3.1 |

Assessment of Student Learning (Assignments) |

Assessment of learning supports course objectives, outcomes, and/or competencies. |

|

3.2 |

Evaluation of Student Learning (Grading Policy) |

A course grading policy is stated clearly. |

|

4.1 |

Instructional Materials |

The instructional materials support the achievement of the stated course objectives/outcomes/competencies. |

|

5.1 |

Learning Activities |

The learning activities promote the achievement of the stated course-level learning objectives or competencies. |

|

5.2 |

Interaction |

Learning activities provide opportunities for interaction (learner-instructor, learner-learner, learner-content). |

Because the online course design review process is intended to be progressive, the review team will evaluate online course design quality at the current required Minimum Standards and provide feedback one step higher, Quality Standards. Online course shells, without students populated in them, will be evaluated.

Professional development workshops will be offered to review and present online course design best practices with respect to Minimum Standards (bronze) and Quality Standards (silver).

The rubric for the next phase of the review process, Quality Standards, is supplied below.

To obtain access to the resources on the Quality Matters (QM®) website, including the full rubric with annotations and examples for online course design, please click here:

Quality Standards, “Silver” (Online Course Design)

|

General Standard |

Specific Standard |

Description |

|

GS1, Course Overview and Introduction |

1.1 |

Instructions make clear how to get started and where to find various course components. |

|

1.2 |

Learners are introduced to the purpose and structure of the course. |

|

|

GS2, Learning Objectives |

2.1 |

The course learning objectives, outcomes, or course/program competencies are measurable. |

|

2.2 |

The module/unit learning objectives or competencies describe outcomes that are measurable and consistent with the course-level objectives or competencies. |

|

|

2.5 |

The learning objectives or competencies are suited to the level of the course. |

|

|

GS3, Assessment and Measurement |

3.1 |

Assessment of learning supports course objectives, outcomes, and/or competencies. |

|

3.2 |

A course grading policy is stated clearly. |

|

|

GS4, Instructional Materials |

4.1 |

The instructional materials support the achievement of the stated course and module/unit learning objectives or competencies. |

|

GS5, Learning Activities and Learner Interaction |

5.1 |

The learning activities promote the achievement of the stated course and module/unit level learning objectives or competencies. |

|

5.2 |

Learning activities provide opportunities for interaction (learner-instructor, learner-learner, learner-content) |

|

|

GS6, Course Technology |

6.1 |

The tools used in the course support the learning objectives and competencies. |

|

GS7, Learner Support |

7.1 |

The course instructions articulate or link to a clear description of the technical support offered and how to obtain it. |

|

GS8, Accessibility and Usability |

7.2 |

Course instructions articulate or link the institution's accessibility policies and services. |

|

8.1 |

Course navigation facilitates ease of use. |

|

|

8.2 |

Information is provided about the accessibility of all technologies required in the course. |

*************************************************************************************************************

Please keep those BYTE newsletter ideas coming! We welcome guest contributors. Please consider answering our call to showcase the outstanding ways that YOU are teaching in the online, hybrid, hyflex, or in-person learning environments.

Stay healthy and safe,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar

*************************************************************************************************************

The Global Campus has adopted the Seven Principles to serve as the framework for online course delivery standards (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). The Quality Matters (QM®) peer-reviewed quality assurance program has been adopted to evaluate course design rigor. Both methodologies align with and parallel the call for learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interactions to promote active learning engagement (QM 5.2). For HLC accreditation purposes, all online courses must include learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interaction (regular and substantive, initiated by the instructor) because correspondence courses are not permitted.

For more information on the Global Campus online course requirements or the SoTL related to them, and/or to curate a conversation about high impact teaching design and delivery practices in your online courses, please reach out to Stacy, the Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar via email onlreview@nmu.edu or telephone (906) 227-1805.

REFERENCES

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3-7.

Standards from the Quality Matters (QM) Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. https://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Vol. 2, Issue 22, February 19, 2021

This week, the BYTE is announcing the call for teaching conference grant proposals on behalf of the Teaching & Learning Advisory Council (TLAC).

All AAUP Teaching Faculty,

The Teaching & Learning Advisory Council (TLAC) is pleased to issue this call for proposals for the TLAC conference grant program for Winter 2021

This semester we are awarding up to five (5) grants between $500 and $1,000 each to assist faculty in participating in scholarship of teaching conferences. Due to travel restrictions for the 2020-2021 academic year, this grant has been modified to allow professional development beyond conferences and workshops. See ideas for conference grant without travel. Also due to travel restrictions during the 2020-2021 academic year, this grant has been modified to allow up to $500 of an award to be used as a stipend to improve instructional practices related to conference participation.

The deadline for submissions is March 1, 2021.

Awarded funds may be allocated for conferences up to one year following the award date and back to the beginning of the semester in which the award was granted. In this case from January 2021 to May 2022.

Amy Barnsley

TLAC Chair

*************************************************************************************************************

Please keep those BYTE newsletter ideas coming! We welcome guest contributors. Please consider answering our call to showcase the outstanding ways that YOU are teaching in the online, hybrid, hyflex, or in-person learning environments.

Stay healthy and safe,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar

*************************************************************************************************************

The Global Campus has adopted the Seven Principles to serve as the framework for online course delivery standards (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). The Quality Matters (QM®) peer-reviewed quality assurance program has been adopted to evaluate course design rigor. Both methodologies align with and parallel the call for learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interactions to promote active learning engagement (QM 5.2). For HLC accreditation purposes, all online courses must include learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interaction (regular and substantive, initiated by the instructor) because correspondence courses are not permitted.

For more information on the Global Campus online course requirements or the SoTL related to them, and/or to curate a conversation about high impact teaching design and delivery practices in your online courses, please reach out to Stacy, the Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar via email onlreview@nmu.edu or telephone (906) 227-1805.

REFERENCES

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3-7.

Standards from the Quality Matters (QM) Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. https://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Vol. 2, Issue 21, February 12, 2021

During my time as your ELCE Scholar, a number of faculty have asked me for clarification regarding the role and function of the Global Campus at our University. Last week, I invited Brad Hamel, Director of Global Campus Operations, to contribute to our newsletter by answering this specific question. A very special thank you to Brad for what you are about to read.

************************************************************************************************************

This BYTE highlights the resources and efforts available to academic departments and distance education students in the Global Campus. Many of the services and resources available do overlap with other departments throughout NMU. It is important to note that we coordinate all efforts with the appropriate university department and tailor those services to the non-traditional and adult student market. The information highlighted below is just a flavor of what we do in the Global Campus, and we would be happy to talk to anyone about a partnership. We want to thank everyone who has made the distance student experience here at NMU a success. A particular thanks to Dr. Boyer-Davis and the past ELCE Scholars who have taken on a significant role in the Global Campus helping shape our future and making sure our educational product is rigorous and what has always been expected from NMU.

Market Analysis/Program Evaluation

As you plan either an entirely new academic program or consider expanding a current program to an online format, the Global Campus staff is able to help with a market analysis or program evaluation. The market analysis, powered by Gray Associates, looks at four factors: 1) student demand, 2) competitive intensity, 3) employment opportunities, and, 4) degree fit. These factors make up an overall score for any given program and are displayed in a color-coded scorecard for an easy to read report. In addition, the report and overall scores are generated for three markets, National, regional (360-mile radius from NMU), and regional (160-mile radius from NMU). Reports are based on the Classification of Instructional Programs (CIP) codes. However, not all program ideas fit neatly into this taxonomic scheme. There are ways the evaluation tool can compile multiple relevant CIP codes to help gauge program viability. Program directors and department heads are the experts for each discipline, and we will work with you to generate an appropriate report. The program evaluation is just one tool in program ideation and can help guide the decision-making process.

Budget Modeling

For new online Global Campus academic programs, we will work with program directors and department heads to set up a budget model that fits departmental needs. The Global Campus strives to follow the Responsibility Center Management (RCM) model of budgeting. In this budget modeling process, we will consider the market analysis to predict the most appropriate enrollment numbers and tuition revenue for your program. During this process, we will discuss the options for either a revenue-sharing plan and or the ability for a Global Campus sponsored faculty position. Program budget models are reviewed each semester with the program directors and department heads. At that time, we will look at individual program trends and discuss any adjustments needed by either the academic department or the Global Campus. Feel free to reach out at any time to talk about opportunities.

Program-Specific Marketing, Recruitment, and Enrollment

Academic programs offered through the Global Campus can benefit from program-specific marketing, recruitment, and enrollment efforts. The Global Campus's creative team works with the academic departments to develop an appropriate marketing and recruitment plan that fits the departments' needs. We have found that program level marketing has produced the best result for the Global Campus programs. Marketing and recruitment plans are targeted to specific audiences through paid digital media, organic social media, direct email, and direct physical mailings when appropriate. Potential students are individually communicated with at each step of the way in the recruitment funnel, keeping them engaged. One initiative we have found to be very beneficial is the pre-admission degree audit for transfer students. Potential Global Campus students are able to submit their unofficial transcripts through a web form for an unofficial evaluation. The audience we are targeting, adult and non-traditional students, appreciate the ability to estimate what is going to be required to complete their educational goals. We have seen an 70% enrollment rate of the students who submitted a request for an unofficial degree audit. Once a student is admitted, they are still engaged with a Global Campus staff member to complete everything required to get enrolled.

Advising and Student Support

Global Campus embraces the success team approach for distance education students. Once a student is admitted, they are assigned a Global Campus advisor and a faculty advisor from the student's major. The Global Campus advisor is there to help the student navigate the distance university experience. The university experience can be daunting for on-campus students to navigate, and that is amplified when the student cannot be here in Marquette to find the resources they need. The Global Campus applies a "Concierge" approach from the first time a student engages with us. This approach is mostly used by our current students who need to navigate the university from a distance. All the Global Campus staff participate in this function and try to handle most student needs with a personal touch. One opportunity for department heads and program directors is that we can help with course forecasting. Our staff can look at the degree audits for your particular major and help determine what courses are needed in the short or long term to make sure distance students can finish their program in a timely fashion. The Global Campus staff also reaches out to continuing students to encourage early registration and continues the outreach right up until the start of the next term.

Alumni Engagement

Now that the Global Campus has a number of graduates throughout the nation and world, we are working with the Alumni Department to make sure that our distance students are engaged with their alma mater. This engagement will undoubtedly help in future recruitment efforts and advance the university's overall mission and vision. The strategies for alumni engagement to students who may never have stepped foot on campus are different from those who had traditionally attended NMU and lived in the great Marquette area.

In closing, the above highlights are just a portion of what the outstanding Global Campus staff and partner university academic and service departments are doing to address distance education students' needs. None of this could be accomplished without the dedication and support across campus. Thank you.

Brad Hamel

Director of Global Campus Operations

bhamel@nmu.edu

*************************************************************************************************************

Please keep those BYTE newsletter ideas coming! We welcome guest contributors. Please consider answering our call to showcase the outstanding ways that YOU are teaching in the online, hybrid, hyflex, or in-person learning environments.

Stay healthy and safe,

Stacy

Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar

*************************************************************************************************************

The Global Campus has adopted the Seven Principles to serve as the framework for online course delivery standards (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). The Quality Matters (QM®) peer-reviewed quality assurance program has been adopted to evaluate course design rigor. Both methodologies align with and parallel the call for learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interactions to promote active learning engagement (QM 5.2). For HLC accreditation purposes, all online courses must include learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content interaction (regular and substantive, initiated by the instructor) because correspondence courses are not permitted.

For more information on the Global Campus online course requirements or the SoTL related to them, and/or to curate a conversation about high impact teaching design and delivery practices in your online courses, please reach out to Stacy, the Extended Learning and Community Engagement (ELCE) Scholar via email onlreview@nmu.edu or telephone (906) 227-1805.

REFERENCES

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3-7.

Standards from the Quality Matters (QM) Higher Education Rubric, 6th Edition. Quality Matters. https://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Vol. 2, Issue 20, January 29, 2021

Let’s keep with the tech teaching tools theme for this week’s BYTE newsletter. A very special thank you to Dr. Wendy Farkas, Associate Professor of English, who wrote to me at the beginning of the semester to share with our readership the outstanding student engagement application that she has been using in her classes with great success, Nearpod: https://nearpod.com/