LaCrosse Lab Explores How Biology and Behavior Connect

By Kristi Evans

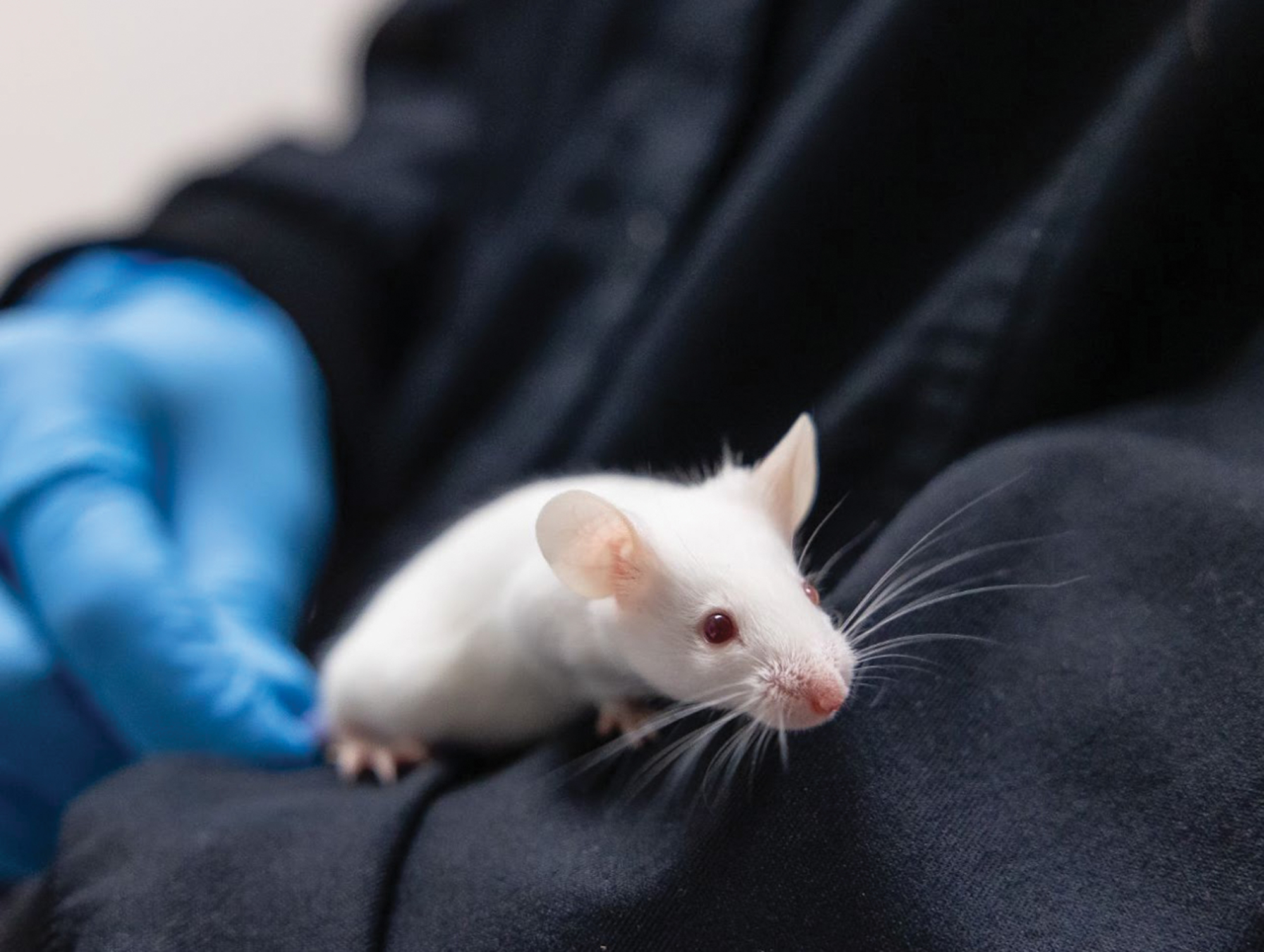

In a storage room in psychology professor Amber LaCrosse’s ’08 BS, ’10 MS Weston Hall laboratory, a new litter of mice has arrived, their tiny pink forms devoid of fur upon delivery. The lab breeds two strains of mice in house rather than pay $70 each to purchase them from an external source. One strain is genetically diverse and better reflects human behavioral variability, while the other is inbred and genetically uniform, which makes it useful for controlled gene studies.

LaCrosse and her students are engaged in translational research, which aims to move scientific discoveries from the laboratory to real-world practice, leading to improved human health. They are using mouse and human models to investigate pharmacological treatments for PTSD; evaluate the abuse potential of Gabapentin; and assess the associations between gene mutations and psychological disorders such as ADHD, anxiety and depression.

One major project explores how the timing and combination of treatments affect recovery after trauma. In the lab’s PTSD model, mice receive four mild electric shocks over five minutes, enough to produce a measurable stress response without lasting harm. After the shocks, the mice are given treatment such as ketamine or antidepressants, mimicking how a human might receive care after a traumatic event.

LaCrosse said the goal is to test what interventions work best when administered hours, not weeks, after trauma. Early data revealed that ketamine may block some of the positive effects of longer-term antidepressant use, a finding that could have implications for how doctors combine treatments in humans.

Another project examines Gabapentin, a medication commonly prescribed for nerve pain and seizure control. Although often considered safe, LaCrosse’s team found evidence that it may engage opioid receptors in the brain and produce rewarding effects at certain doses.

“Gabapentin shows up in about 90% of opioid overdose fatalities,” LaCrosse said. “We’re finding that it’s not as benign as once thought, especially in people with a history of addiction.”

LaCrosse’s students use classical conditioning tests to observe whether mice seek environments where they received the drug—a key sign of its addictive potential. In addition to animal studies, the LaCrosse Lab conducts human genetics research. Students collect cheek swabs to analyze for a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), or a variation at a single position in a DNA sequence, on the MTHFR gene, which affects how the body processes folate, a crucial B vitamin that helps prevent serious birth defects. Entry to a room where this research is conducted is severely restricted to avoid the risk of contamination.

“We know neurodevelopmental disorders usually involve some sort of genetic predisposition combined with an environmental insult at a critical period, and one of the critical periods is going to be in the womb while the baby is developing,” LaCrosse said. “What we’re seeing right now is a bit of a link between a homozygous mutation in the MTHFR gene and inattentive ADHD—not so much the hyperactive form. We’re also looking at correlations with anxiety and depression.”

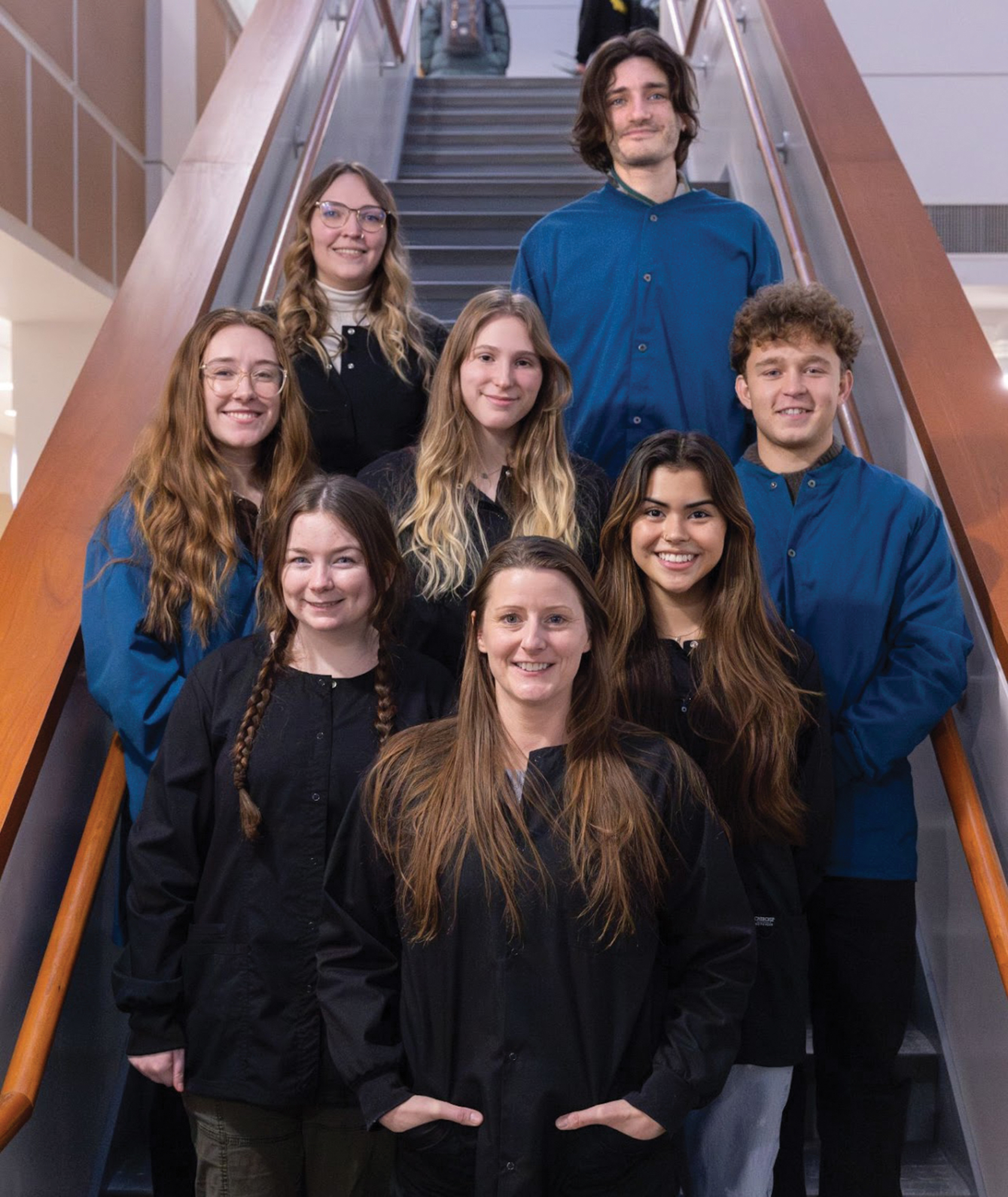

With up to 21 undergraduates, three graduate students and a research associate at one time, the LaCrosse Lab is one of NMU’s most active research groups. Students gain hands-on experience in behavioral testing, molecular analysis and data interpretation.

“Some students come in with no research experience and end up publishing papers,” LaCrosse said.

“The best part of my job is seeing them realize what they’re capable of. Everything we do is aimed at understanding how biology and behavior connect. If we can use that knowledge to make recovery faster or safer for people, then it’s worth every hour we spend in here.”