Inside Weston Hall’s main entrance from the academic mall, a taxidermy display of a wolf in a glass case commands attention from those who pass by. This is a highly visible and majestic example of Great Lakes fauna showcased on campus, but it is complemented by many other specimens housed behind a nearby door to the Northern Museum of Zoology. Maintained by Biology Department faculty curators and student collection managers, the museum supports teaching and research within the department and beyond.

“Obviously, its primary strengths are northern Michigan animals, some of which we collect out in the field, but we also have some things that are from a bit farther afield that are kind of exciting for our students to see,” said Professor Kurt Galbreath, who researches small mammals and their parasites.

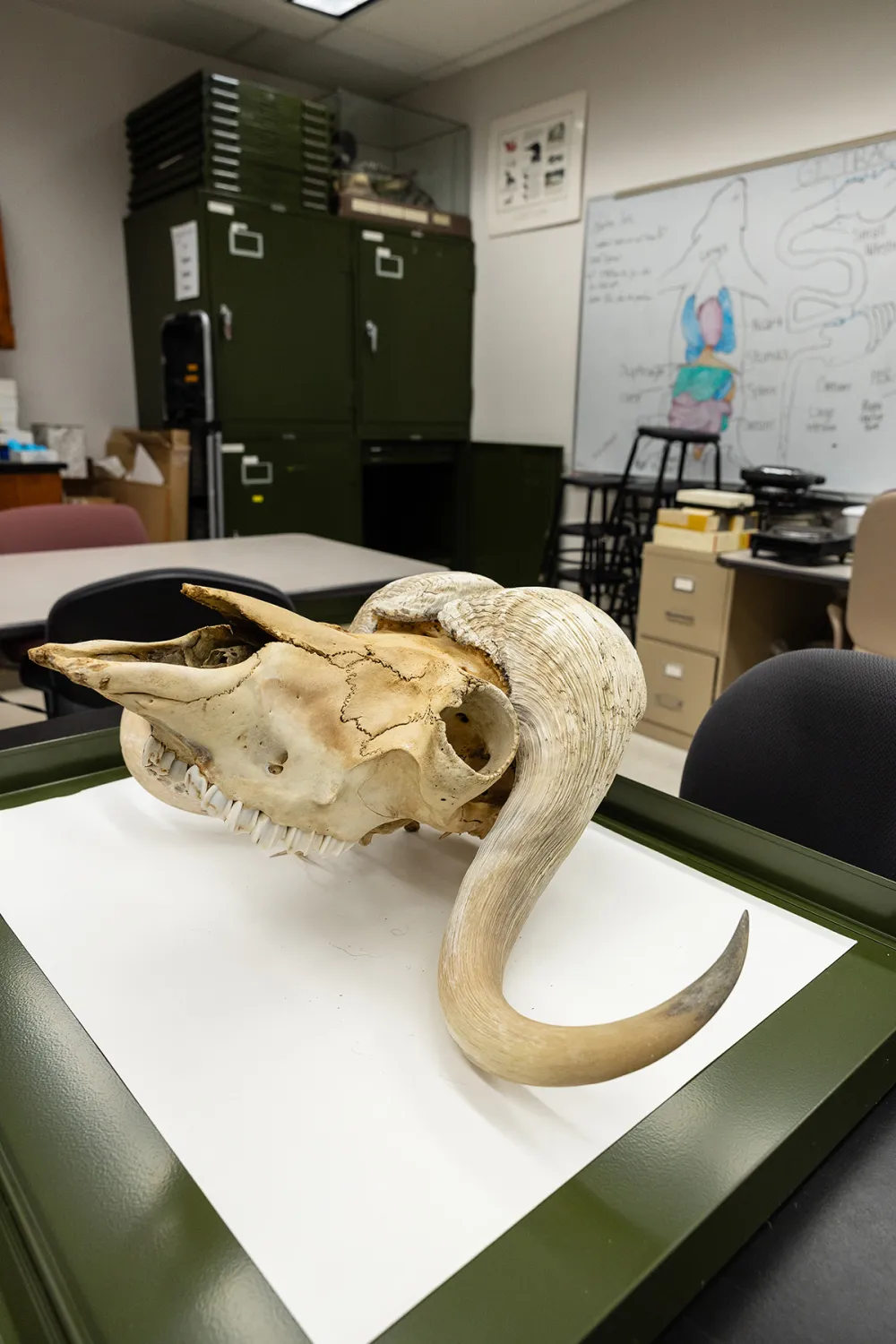

One of Galbreath’s favorite unique specimens is a musk ox skull that an area doctor got, perhaps in the Northwest Territories, and stored in his garage for a while before donating it to the department. Specimens like this have relatively limited scientific value, he said, because the precise details of where it came from and when are not known.

"You can look at pictures in a textbook, but to be able to fit the jaws together and see how those teeth work together is really powerful for students."

“But it’s great for teaching about the different lineages of mammals,” he added. “You can infer a lot about the biology of an organism based on the anatomy of the skull. And the structure of the teeth reveals dietary habits. This is an herbivore because they’re highly effective for chopping and grinding plants and lichens up on the tundra, as opposed to how a carnivore’s teeth would look. You can look at pictures in a textbook, but to be able to fit the jaws together and see how those teeth work together is really powerful for students.”

Some specimens originating from outside the region were seized at various ports of entry by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) during attempts to bring them into the country illegally. They are marked with identifiable blue tags.

“The USFWS is always looking for universities that would be interested in using confiscated specimens in their teaching,” Galbreath added. “One of the more exotic items we received on permanent loan from the USFWS is an oosik, or the bone that fits in a walrus’ penis. As you might expect, the students get a kick out of that one.”

There is also a horn from a saiga, billed as “the world’s quirkiest antelope” with its large, bulbous nose. The massive migrations of saiga, once millions strong, rivaled those of the modern-day wildebeest. Now the species is threatened by poaching and habitat destruction, and largely confined to Central Asia.

“The big, charismatic specimens are exciting, but a lot of the most useful information about an ecosystem originates from the humble, small mammals,” Galbreath said. “They’re like the canary in the coal mine. If the environment is changing in a way that is shifting the ecological community, you’ll see it first in the ground-floor species such as mice, voles and shrews. They’re at the base of the trophic pyramid, and the food that predators go after. Something that happens to them affects other species further up the pyramid.

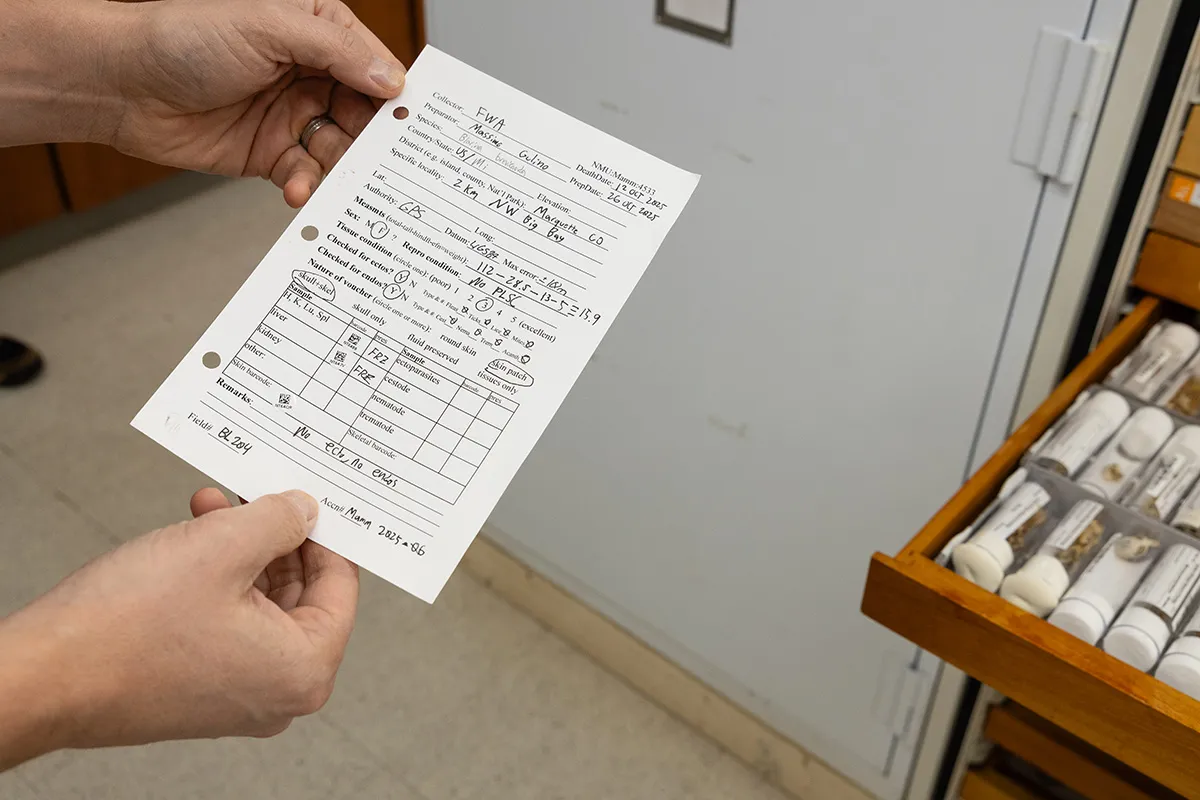

“We kind of preach the extended specimen ethic, which means if you're going to collect a mammal, you have a responsibility to maximize the data you can get out of it. One way to do that is by collecting all of the other things associated with that animal like parasites and tissue so we have a record of that. I think of the mammal itself as sitting at the center of a whole constellation of data points. And all those data points tell us more about that organism and the environment it came from. That makes those specimens more valuable to the scientific community.”

The Northern Museum of Zoology’s vertebrate collections include the following: fluid-preserved fish; amphibians and reptiles; bird skins and eggs; and mammal skins, skulls, skeletons and frozen tissues. The invertebrates—the largest and most diverse collection, numbering in the tens of thousands—include aquatic and terrestrial insects, Lake Superior wave-zone invertebrates, freshwater sponges, gastropods, leeches and parasites.

Galbreath credits student collection managers like Owen VanAntwerpen with ensuring that the museum’s processes for data collection and loan requests operate smoothly.

“Ever since I was very young, I dreamed of becoming a scientist. Being in the museum allows me to be surrounded by science and involved in the process of making science happen. I find that very exciting. I have a lot of various interests relating to biology, but museum science has become one of them here.”

—Owen Vanantwerpen

“I mainly work on getting the data people collect in the preparation of specimens and enter it into our digital Arctos database,” said VanAntwerpen, a biology major with a concentration in ecology. “This makes it possible for scientists from around the world to access the data and request specific specimens that they want to work with for their research, and for us to track all of our data through a more stable, long-term method.”

VanAntwerpen’s role includes coordinating the many student volunteers who help the museum function. He also handles loan requests that come in by pulling the appropriate specimens from storage and bringing them down to teaching labs, then returning them to their proper place when classes are finished using them.

The Northern Museum of Zoology was established in 1974 by J. Kirwin Werner and Lewis Peters.

— By Kristi Evans